I was conceived in the womb of one poet and sired by another. Poetry, I suspect, was ruling my stars from the very first moment of my being. I had no way of avoiding its grips.

–Nabaneeta Dev Sen

*Article continues after advertisement

My mother couldn’t remember a time in her life when she did not write poetry. Raised by two celebrated poets, Radharani Debi and Narendra Dev (and named by Rabindranath Tagore), she published her poems in a magazine at age seven, in both Bengali and English. Her first book of poems, Pratham Pratyay (First Confidence), was greeted with much acclaim the year she turned 21, just before she left for Harvard. She grew to be immensely popular in every genre she chose—fiction or non-fiction, feminist essays or children’s books, travelogues or journalism—and her books in prose far outnumbered her poetry collections. And yet, throughout her life, she made no secret of the fact that she would always identify herself as a poet. “No matter what I write, it is always a poet writing,” she wrote with her self-proclaimed “poet’s immodesty,” for “it was in the looking glass of poetry that I saw my face for the first time. Poetry was my first confidence.”

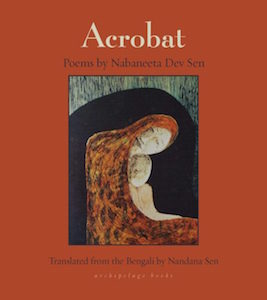

Indeed, poetry was not only Nabaneeta’s “first confidence”—her first allegiance, her first love—but proved itself, time and again, to be her unwavering life partner. As a child, she cherished the little black notebook Radharani had given her for writing poems, which initiated a lifelong compulsion to carry a “kabitar khata” with her everywhere. Right until the last weeks of her life, Ma kept scribbling lines of poems in her notebook, poems which remained incomplete as much for her ill health as for her incurable perfectionism. She signed the agreement for Acrobat with great rejoicing just two weeks before she died. Although my mother had over a hundred books to her credit, our book was going to be, incredibly, her first one published for an international audience. She announced the birth of Acrobat with uninhibited excitement in her very last weekly column, one she dictated from bed as she waited to get her strength back.

Ma, always as adored for her spirit as she was for her words, was characteristically undaunted by the gravity of her illness, although she understood that it was terminal, that there was reason for haste. We started selecting poems for Acrobat—a handful of her translated poems had been in circulation for years, but my mother was eager that our book should introduce newer translations, curated from six decades of poetry. So we made a first (and modest) list of poems together, poems that she insisted that I must translate. And that’s as far as we got.

I have now translated all the poems on that list, and twice as many more. I’ve included in Acrobat my mother’s own stunning translations, her rare English poems (written mostly when she lived in London), and a political poem powerfully translated by my sister Antara for her literary journal, The Little Magazine. The collection also contains some of our first translations together, poems that Ma and I had worked on over three decades ago, as well as poems from Make Up Your Mind, my translation of her last book of new poetry.

It has taken me a year to complete Acrobat—not that long, I suppose, considering that it represents an intricate body of work woven over 60 years—a year in which I have missed her at every word, with every line. There is so much to say about a lifetime of luminous poetry. But if my mother were introducing this book to you herself, as I had fervently hoped she would, I know she would have begun by telling you how deeply she believed in the vital necessity of poetry, and in every freedom it delivers:

I speak for poetry as being central to a woman’s freedom. Yes, I am partial, I cannot be and do not wish to be objective in this one respect . . . It is not only the printed word that spells inner freedom for us women, there are oral songs composed by village women. They sing their own sorrows and anguish . . . Poetry is a means of our survival, it is a window through which we can breathe.

As a young wife and scholar shuttling between America and England, Nabaneeta had stopped publishing poetry for a while, focusing instead on her family, and her pioneering research on the oral origins of epic poetry. When her marriage fell apart, she returned to India with two young daughters. Her recent separation and the anticipated divorce—which would be the first of its kind in her social and literary circle in Kolkata—became a scandal that was suffocating for her. But within a year, Nabaneeta published her second book of poems (after a gap of thirteen years), re-opening that window through which she could breathe.

There is so much to say about a lifetime of luminous poetry.

Poetry brought Nabaneeta the kind of “freedom” that was most precious to her—the freedom to explore her own broken voice, and to secure her identity in a timid world that initially struggled to find a place for her again. It gave her the freedom to reach out to a large and responsive audience, to discover another kind of love. And till her last days, she stayed strongly connected to her readers: “People feel they can trust me, they feel I will understand. They feel I am of some use to them when they need human warmth . . . They feel I’m a part of their lives, and, in a way, they become a part of mine too. It’s a blessing.”

Beyond providing Nabaneeta with a devoted readership and a powerful public platform, poetry also paved for her a private route to healing. Poetry allowed her the freedom to unveil her deepest emotions, to “sing her sorrows” or register her dissent, to write off layers of social and linguistic conditioning and write out her heart with no restraint. Throughout her life, poetry empowered Nabaneeta to find and keep her balance during upheavals of every kind, whether it was the ferocity of love or the anxiety of motherhood; the shock of rejection or the grief of bereavement; the despair of communal violence or the outrage of gender-based injustices—all of which developed into abiding themes in her poetry. “Poetry would offer, as ever, the final refuge. It never let me down. Every time I was flooded over, and drowning, poetry pulled me up onto dry land. I survived.”

Nabaneeta had a profound and primal need for poetry, not only as a way to cope, but as a way of forming herself. It was a compulsion that came from deep within: she often spoke of the inner pressure she felt that forced her to write. “How do I know who I am until I have ‘written’ myself, and read myself? There I was, me, Nabaneeta, taking shape, on a piece of paper.” It was critically important for her to write each and every day; a day without a single line of poetry was, for her, “a sad day, a barren day.” And yet, shortly after her divorce was finalized, Nabaneeta made a conscious decision to take a step back from her poetry. Why? Because her poems, she felt, were giving her away.

Nabaneeta had always believed that her poems anticipated and understood what she was going through far better than she herself was able to. At that turbulent moment in her life, it felt as if her poetry was, involuntarily yet relentlessly, exposing the rawness of her pain; and in so doing, igniting the readers’ obsessive curiosity. “In the case of a woman writer, readers are not content with the literary work alone,” she wrote. “They are thirsty for glimpses of her personal life, for extra-literary information.”

There was another reason why Nabaneeta took a break from writing poetry for public consumption, and that, too, had everything to do with being a woman writer. Even when her poems were not inspired by her own life, her readers concluded, rather oppressively, that they were autobiographical. Nabaneeta wrote and spoke extensively about this inescapable “imprisonment” of a woman writer’s autonomous identity:

A woman writer is constantly watched, like prisoners in a jail who are made to parade before the warden every morning. Her name becomes an essential part of the text that she produces, along with her whole personal life and her body . . . I stopped writing poetry and shifted to humorous prose because my readership had started finding deep personal messages about my private life in my poems, which bothered me. Inevitably, the woman writer’s personal life becomes an integral part of her writing, to be analyzed and approved by the reader, which is not something the male writer experiences or suffers.

Therefore, to resist being forced against her will to be “part of the text” in her poetry, Nabaneeta made the radical choice of willingly entering the text in her prose. Throwing open the doors to her “private life,” she invited the curious crowd into her household and “let them see it for themselves.” She decided to write about herself and her seemingly “dysfunctional” family, which in fact functioned perfectly without any men, in her raucously fun-loving “broken home.” Nabaneeta’s inimitable prose, which was as truthful as her poems but intensely funny, quickly gained in popularity. Though she could not stay away too long from poetry—“my companion, my fulfillment, my frustration”—a part of her would always regret the great demand that arose for her stories: “I think it harmed me in some way, because as I started writing prose the flow of my poetry decreased.”

The truth is, her narrative prose did more closely reflect the public persona of everyone’s beloved, ever-optimistic and rambunctious “Nabaneeta Di.” Candid yet satirical and observant, her stories, essays, travel writing, children’s books and journalism all had a seriousness of purpose and a strong feminist core, but were warm, witty and spry. The vastly popular, as opposed to literary, following she attracted was drawn above all to this category of work, which overflowed with her natural charm and her famous joie de vivre. But if she opened her heart in her prose, Nabaneeta continued to bare her soul in her poetry, without inhibition. It is not easy to distill 60 years of poetry into one slim volume, yet across the years there is a remarkable and obvious consistency in the themes, refrains and tone of her poetry. In contrast to her work in other genres, her poetry is visceral and inward-looking, often painful and sometimes disturbing, but always breathtaking in the power of its truth. Nabaneeta loved to laugh at herself in her prose; but she was never afraid to cry in her poetry.

In fact, Nabaneeta often made the observation that she had grown up with two eyes that were physically “quite un-alike”; one did not know how to smile, and the other could never shed a tear. “I use the smiley-eye to write funny stories. The sad one looks within, and writes poetry.” However, even if her two eyes did look and behave as differently as she believed, they were nonetheless “alike” in the candor and boldness of their gaze. Intrepid as ever, Nabaneeta looked long and hard at herself through her work. Her unforgiving honesty rounded into a self-deprecating humor in her prose, that irreverent laughter that was so infectious and loved; equally, it added a sharp edge of anxiety and self-questioning to her poetry, layering it with a depth of palpable sadness.

Nabaneeta loved to laugh at herself in her prose; but she was never afraid to cry in her poetry.

For Nabaneeta, poetry was a momentous, even sacred, responsibility, a quest for a deeper, more elusive truth, and she held herself accountable for every choice she made as a poet. Even as she embraced poetry as a great blessing in her life, she often noted (only half-jokingly) that she also felt cursed by poetry—it was “like an inevitable curse that had descended upon me at the moment of my birth.” Throughout her writing life, her poems revealed a profound recognition of not only the freeing power of words, but also their destructive potential. Whether she described language as a wild stallion or a fiery volcano, as the uncaring aristocracy or a cunning moneylender, as poisonous stings or blood-shedding weapons, we see Nabaneeta grappling with the devastation that can lurk behind language—and even invoking it, in her own words, for “the sake of poetry.” More than her prose, it was her poetry that exposed the contours of her own fraught relationship with language, as starkly as it captured her frustrations with the writing process. “Poetry is like war,” she wrote. “A war with oneself. Finally, only when there is victory and peace, poetry follows. Poetry has to be earned.”

In turn, poetry earned and retained primacy in the creative sensibility of Nabaneeta, who saw herself, in her own words, as “a poet before anything else.” Perhaps it was because poetry was “entwined in the very nerve-center” of her being, that it even found ways to insinuate itself into the other genres in which Nabaneeta shone throughout her long career, including her novels and her academic work. While discussing the ways in which her writing reflected her soul and her heart, we must not overlook the brilliant work that came together in her head: Nabaneeta was a widely recognized and exceptionally creative academic, a distinguished professor of comparative literature, whose scholarly work had an extensive focus on poetry.

As a young researcher, first at Harvard and then in Cambridge, Nabaneeta examined the linguistic composition and thematic bases of epic poetry across the world, calibrating the great Indian epics against their counterparts in the Western canon. Her analysis of the verse of Valmiki Ramayana broke radically new ground, providing evidence of the oral rather than written composition of the epic’s early portion (Balakanda). Equally pioneering was her feminist study of the retellings of the Ramayana by women poets from the sixteenth century till the present, the subject of her acclaimed Radhakrishnan Memorial Lecture series delivered at Oxford University in 1997. And Nabaneeta’s own creative re-imaginings of the epics from the perspectives of women, composed in prose as well as poetry, left a blazing trail for younger writers and scholars to follow.

Poetry played a leading role in many of Nabaneeta’s novels as well, in form as well as content. She revolutionized the fiction form in her bestselling novel Bama-Bodhini (A Woman’s Primer) when she incorporated poems and ballads into its narrative structure, letting the story unfold through poetry as well as prose. And her novel Prabashe Daiber Bashe (In a Foreign Land, by Chance) centers on a young Bengali poet who, after emigrating to England, makes a calculated decision to write her poems only in English. Thus, as early as 1977, Nabaneeta had anticipated the global explosion of Indian writing in English, addressing head-on the linguistic and political dilemma of choosing “the language of the ruler” over your own mother tongue.

Nabaneeta was a truly bilingual writer (almost all her academic writing was in English), but as a poet, she consciously eschewed the choice that her novel’s protagonist had made. In fact, Nabaneeta’s own story was exactly the reverse: when she relocated to Kolkata from London, she resolved to stop writing poems in English, even though she found the unencumbered anonymity, the “cultural distance” and “verbal personality” of English to be liberating. “In English I could express my anger, my thirst, far more openly and powerfully, irrespective of a reader’s sentiment, because I was addressing a faceless reading public . . . In English, only the poem exists.” Nabaneeta readily acknowledged that English allowed her the freedom to “use language without social-sexual inhibition,” which was simply not possible for her in Bengali (one reason, perhaps, why Ma translated so few of her English poems into Bangla). She was also acutely aware of the many advantages, national and international, of choosing to write in English: “In this country mother tongues we have many, father tongue just one. A better control over the father tongue gets you a better deal in the present system of things.” And yet, Nabaneeta was unswerving in her election of Bengali as her preferred language for all of her creative writing.

“I wrote in Bangla because it was a political choice for me,” she stated without hesitation whenever questioned. She saw this dilemma as a crisis of loyalty, and of identity—not only because she belonged to a generation of writers who rejected the colonizers’ language, but even more critically, because she was deeply worried about the future of regional languages and literatures in India. “There is a cultural distance growing between us and our children, who are moving away from their mother tongues.” Younger generations across multilingual India were losing their connection to their regional heritages, she warned, owing in part to the dominance of Hindi popular culture, but also to the proliferation of Indian writing in English. Consequently, regional literatures were in danger of seeming increasingly obscure, redundant, or obsolete, she feared. When a journalist asked Nabaneeta why she no longer wrote poetry in English, her unequivocal answer was: “Because I believe it is very important that we write in our regional languages. That way you are serving yourself as a poet, and also serving your language.”

[pulquote]She was acutely aware of the many advantages, national and international, of choosing to write in English, yet she was unswerving in her election of Bengali as her preferred language for all of her creative writing.[/pullquote]

Nabaneeta, as voracious a reader as she was prolific a writer, admired and keenly followed new Indian writing in English; at the same time, she recognized the threat that it unwittingly posed. Speaking on “International Poetry, Translation, and Language Justice” at Columbia University in 2017, she drew attention to the scarcity of English translations from regional languages; as a result, she con- tended, “Indian literature in English has only naturally raised itself to the status of representing all of India, when only 2% of the nation still read English.” Therefore, parallel to her steadfast call to action for writing in the mother tongue, Nabaneeta campaigned hard for translation as “a practical tool for empowerment,” one that could, in time, rescue regional literatures from extinction:

Good English translations of Indian literature are urgently needed today as lifesavers, to protect regional literatures from being wiped out in the tsunami of globalized Indian literature in English. We need to show the world the features of India’s mature inner face, expressed through its many-colored regional cultures . . . If good translations are available to all, then the world will not have to depend on the Indian writer in English as the only literary interpreter of Indian culture.

Nabaneeta attributed the three main “discontents of translation” in India to quantity, quality, and availability. There were not enough English translations of regional literatures; most translations did not do justice to the original texts; and our translations were poorly marketed and distributed within and outside India. Consequently, regional literatures were being relegated to a lower literary status: “This false perception has to be met with powerful translations of modern Indian classics,” she argued, time and again.

As a language activist as well as a champion of poetry, polyglot Nabaneeta walked the talk to the fullest. A dedicated and dexterous translator, she translated into English the sixteenth-century Ramayana of Chandrabati, the first woman poet who wrote in Bangla (also the first Bengali poet to rewrite Ram’s story from Sita’s perspective). Nabaneeta’s English translation of Chandrabati has been hailed, nationally and internationally, as a radiant and path-breaking presentation of an unrecognized classic.

Nabaneeta was equally passionate about translating poetry into Bangla—a language shared by 250 million worldwide—particularly women’s poetry from across India, and indeed, around the world. It was her firm belief that translation could effectively counter the “divisive forces” of “caste, class, religion, gender, region, language,” and that it was “especially important to get to know one another in these days of fragmentation and disconnection.” Nabaneeta wrote and spoke of translation as a unifying “act of pulling down the fences, of bringing neighbours together,” as an empowering tool to “help us realize the falsity of boundaries” and find our “deeper, inner bonds.”

Blessed with a formidable gift for languages, throughout her career Nabaneeta devoted much of her time to translating poetry from languages as far apart as Kannada or Kashmiri, Gujarati or Malayalam, Chinese or Russian, Japanese or Hebrew. If she didn’t know a particular language well enough, she punctiliously used a bridge language, or the help of a collaborator who was fluent in it, until she was satisfied with the truth of her translation. Even when she was severely ill, Ma pored over the proofs of Shara Prithibir Kabita (Poems from the Whole World), her last book of translations, published a few weeks after she died.

My mother’s lifelong commitment to translating women’s poetry brings us back full circle to where we started: her unshakeable faith in poetry as an instrument for women’s freedom and unity. Speaking at a conference of South Asian Women Writers, she identified women’s poetry as the platform “where all languages meet and melt into one another” to give voice to “the shared memories, the shared apprehensions, the shared metaphors,” representing a collective quest to “be empowered by the Word, to be freed by the Word.” But for Nabaneeta, in addition to being a “precious bond that joins us in sisterhood,” poetry embodied a mighty matrilineal legacy to be passed down from generation to generation.

Nabaneeta was born, we know, into a home replete with poetry. She owed her love of languages, as well as her expertise in poetic forms and structure, to her erudite and soft-spoken father, the poet Narendra Dev. But it was her uncompromising mother Radharani Debi, with whom she shared an intimate if intricate relationship, who showed Nabaneeta the transformative power of poetry. Married at 12 and widowed at 13, Radharani educated herself entirely on her own, re-married (quite scandalously at the time), and became a bestselling poet who wrote under two distinct identities (with two very differently “feminine” poetic personalities). Till her last years, my grandmother remained Ma’s most devoted reader, her most scrupulous editor, and her strongest literary critic. Nabaneeta proudly acknowledged, time and again, that she had inherited her profound faith in poetry from her mother:

Looking at Bengali women’s poetry from Chandrabati to Radharani to myself, we have seen marginal women craftily moving center stage through poetry. We see that poetry can become a powerful weapon in the hand of the disempowered and can elevate their lives. I am grateful to my mother’s poetry, which opened the door for me to walk through.

I am not a poet, though my mother had wished, not too secretly, that I would become one. But I, too, am grateful to my mother’s poetry, which opened the door for me to walk through—as a woman, a mother, a writer, an actor, an activist. Our mother’s poetry has always been a tremendous source of strength for me and my sister, just as her own mother’s was for Ma.

When I left home early to study, Ma and I stayed connected through her poetry (apart from the six or nine minute “trunk calls” between Kolkata and Boston every Saturday morning, calculated then by increments of three minutes). Though this was long before the magic of email, Ma, always a passionate letter-writer, found generous ways to share her poems with me. Blue aerogrammes and yellow envelopes regularly arrived from India, usually filled with lengthy remonstrations, but sometimes, with poetry. Whenever she sensed a sadness in me, or if ever there was a special reason to celebrate, lines of poetry arrived by post a few days later—sometimes quiet and wise, sometimes silly and joyful, but always comforting. Clippings or photocopies of her published poems were often lovingly folded into the heart of her letter.

Nabaneeta had a profound and primal need for poetry, not only as a way to cope, but as a way of forming herself.

In truth, Acrobat had its beginnings well over thirty years ago, when Ma and I first started translating her poems together. This was born purely out of need—I wasn’t focused on translation at that time. But Ma was often invited to give poetry readings while on a lecture tour, and had little of it available in translation. On such an occasion, when I was a Freshman at Harvard, she was requested by the Bunting Institute to present and discuss her poetry in a special session for the Radcliffe Fellows—and we had to quickly get to work. It was ironic of course that, while Ma was deeply committed to translating the work of women poets across the globe, she translated her own only under duress. We spent a good part of my Sophomore spring break working on translations too, when I visited my mother at Colorado College, where she held the Maytag Chair of Creative Writing and Comparative Literature. I cherished that time we spent together working through and arguing over her poetry, a time that came to an abrupt and heartbreaking end when my grandmother had a stroke, and Ma returned to Kolkata.

Despite her untiring advocacy for translation, my mother continued to resist translating her own poems, a reluctance I found especially frustrating because whenever she did it, her own translations were truly beautiful—and far superior to any done by others. But Ma never hid the fact that she lacked the patience and indeed the motivation to translate her own poetry. As a perfectionist, she agonized over every syllable of every poem she wrote in Bangla, but once she completed a poem, she felt her work was done. “I would rather write a new poem,” she would say, than revisit one through translation.

So, our translations were always sparked by practical necessity: Ma needed to have strong translations of her poetry available for her own use. I did not aspire to become the primary translator of Ma’s poetry, nor was it important to me to be credited for the work we had done together. In 2012, while we were on a trip to China, Ma had an opportunity to present her poetry in Beijing’s Bookworm bookstore, and I was asked to be “in conversation” with her. As she had a book of new poems out (Tumi Monosthir Koro), we were keen to include those in the discussion and I quickly translated just a few for the reading, translations that Ma really liked. So, on my mother’s 75th birthday the next year, I presented her with Make Up Your Mind, a bilingual edition of my translations from her book. (It was a self-published print-run of only 75 copies, which was subsequently reprinted several times in much larger quantities). Because this project was planned as a birthday surprise, I did not involve Ma in the translations at all; she told me afterwards that she was delighted that I hadn’t. It had “freed” me, she said, to make my own interpretations and trust my instincts, while staying true to the words, images, and rhymes on the page. And that, in essence, is what I’ve tried to do in Acrobat.

As we know, poetry is never easy to translate, even less so if the poet favors complex rhyming and rhythmic structures, and repetitions that are sublimely melodious or pointedly dissonant. My mother, who called herself “furiously obverse” in her poetic diction, also had an extraordinary talent for creating new words, powerful neologisms that fit perfectly and indispensably into a poem, but were nigh impossible to translate. In addition, even as her images sparkled with piercing originality, they often caressed her own cultural history with a tender specificity (and at times, dissension). And if conveying all of that in English wasn’t demanding enough, Ma loved using words that had multiple meanings and resonances, forcing a translator to make some very difficult choices.

___________________________________________________

From Acrobat by Nabaneeta Dev Sen, trans. Nandana Dev Sen. Used with the permission of Archipelago Books.

Nandana Dev Sen

Nandana Dev Sen is a writer, actor, and child-rights activist. She has written six children’s books (translated into more than 15 languages globally), and starred in 20 feature films (from four continents, in numerous languages). She has represented UNICEF, RAHI and the National Commission for Protection of Child Rights to fight against child abuse, and to end human trafficking. Winner of the Last Girl Champion Award (and multiple Best Actress Awards), Nandana is Child Protection Ambassador for Save the Children India. Nandana is on Facebook and Instagram at nandanadevsen and she tweets @nandanadevsen as well. You’re welcome to visit her at www.nandanadevsen.com.