A Lasting Gift: Remembering My Friend Kim Chernin

Gail Reitano on the Life and Career of a Beloved Mentor and Kindred Spirit

Kim Chernin’s memoir In My Mother’s House has lived in me ever since I first read it in the 1980s, when I was living in London. The uneasy daughter, the uneasy mother, the mother’s life of activism, the struggle for justice, a daughter’s search for meaning in her life independent of her mother: these themes spoke to me. In the decades since, I had forgotten Kim, except for the picture on the cover—that naughty look, those warm, knowing eyes. In the strange way of chemistry between humans, that expression has never left me.

I met her on a cold, rainy Sunday, the kind of day when you want to stay home and drink endless cups of tea. But there was an event at Mesa Refuge, the northern California residency for writers founded in 1997 by the writer and entrepreneur Peter Barnes. There was to be a reading by several nature writers. I was stuck on a novel I was writing and thought the readings might knock loose a little inspiration. But as the event neared, I felt less and less like attending. Had I not gone, it’s hard to imagine what would have happened or not happened, because that day changed the trajectory of my writing life.

My husband and I were sitting on a sofa waiting for the readings to begin when Kim and her partner Renate Stendhal sat down next to us. We were strangers, but immediately the four of us began a cascading conversation, and the sofa became our own little island in the midst of the event going on around us. We carried on until told to be quiet, but we picked right back up as soon as the readings were over, talking over snacks in the kitchen before circulating around the event. As my husband and I were about to leave, Peter Barnes, assuming we hadn’t met, introduced the four of us—which made us laugh—and I caught Kim’s full name. I felt intrigued, excited; that day marked the beginning of our friendship.

Kim offered to read the novel I had been working on, as well as an essay about the encounters I had had with Andy Warhol, who was my landlord when I lived on the Bowery in New York City. I envied his success, and the cool, hip entourage that formed around him and supported him. I was a writer with an all-consuming day job, and I would wake in the middle of the night to work on my Bowery stories. What I lacked was a community. That would have been around the same time that Kim was first starting out, encouraged to publish her first books by a strong, active group of feminist writers.

We shared a sense of justice, a love of the underdog.

Once Kim, Renate, and I began our informal writing group, the three of us met regularly, shared pieces, edited, suggested, argued. Kim was forceful in her critiques and rarely did she feel the need to agree with Renate or me. Kim’s and Renate’s observations were spot-on—not surprising, given that they were both fine writers in addition to being therapists and working editors. For the first time in my writing life, I found myself with access to an expertise that went far beyond my hopes or expectations.

Kim’s writing explored a wide range of subjects: gender identity, lesbianism, body image, and psychoanalysis, which she had done for 20 years with prominent San Francisco analysts. But I was particularly interested in how she handled her Jewish identity. We shared a sense of justice, a love of the underdog, and a belief that what society and religion sought to separate, and isolate, we could find solutions to using the written word.

The author of The Flame Bearers, Kim was the perfect person to advise me on the spiritual longings of my main character, Marie Genovese. Kim encouraged me to bring forth Marie’s Italian American rituals, her herbs, spells, and magical baking. When Marie’s near-hallucinogenic experiences with her dead mother needed to straddle the real and the imagined, Kim recommended William James’s The Varieties of Religious Experience, which gave me the confidence to write about what is unseen. In her own writing, Kim frequently worked with magic, myth, and religion, and throughout her life, she wrote mystical poems. She would never share these, considering them private until much later in life, when she was urged by her extensive feminist network to publish some in Dark Matter: Women Witnessing.

Kim, Renate, and I liked to talk about our mothers. One day, we were sitting in my kitchen, and I confided that mine had never gone to college. Kim leaned forward and with conspiratorial glee, said, “Neither did mine!” “Nor mine,” said Renate. This confession launched the three of us headlong into a discussion about class and family relationships, topics that Kim had explored in her writing, in particular in her first memoir and The Woman Who Gave Birth to her Mother.

I’d participated in writing workshops for many years: in several courses at the University of London, six summer workshops at The Community of Writers in the Sierra, and for four years in a group led by the poet Robert Glück in San Francisco. For a writer, the ideal situation is a community without distractions, one that is separate from the demands of family, a place to renew one’s commitment to the craft.

At this point, though, my work had reached the stage where I also needed mentoring. Kim stepped into this role with an enthusiasm that surprised me. The timing was right; by her own admission, she had reached the point in her career where she trusted her large body of work would find its rightful place. Her output would eventually total more than 20 published books, six unpublished, archived manuscripts, and a number of poems. She was a fast writer and surefooted in her decisions about every aspect of writing.

Kim loved food. For several years, she and Renate came to our house for Christmas dinner. She had written honestly about having experienced anorexia and bulimia as a young woman, but her relationship to food had changed over the years. She was obsessed with good food and she especially loved deserts. If Kim were still alive we would probably, on May 7th, be baking an Italian love cake together, and we would be continuing our workshop.

If we’re lucky, we find our mentors, our teachers, and our community once we leave the comfort of home and the tea kettle. For eight years I felt held, appreciated, and seen, and that is a lasting gift.

__________________________________

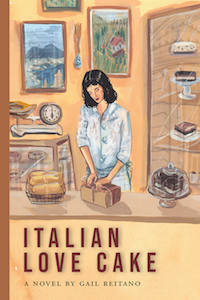

Italian Love Cake is available from Bordighera Press. Copyright © 2021 by Gail Reitano.

Gail Reitano

Gail Reitano was born and raised in the southern New Jersey Pine Barrens and currently lives on the West Coast, north of San Francisco. Her work includes fiction, memoir, and the personal essay, and has appeared in the anthology Songs of Ourselves: America's Interior Landscape, Glimmer Train Press, Catamaran Literary Reader, and Ovunque Siamo: New Italian American Writing, among others. ITALIAN LOVE CAKE (Bordighera Press, 2021) is her first novel.