Jess and Robert Duncan pursued separate artistic paths—the former as a visual artist, the latter as a poet, though each experimented with the other’s chosen medium. Jess, who had a lifelong interest in the play inherent in language, wrote poetry and prose, and Duncan, who was drawn to the open form and movement he perceived in abstract expressionism, painted and drew. Yet neither approached the facility with which the other engaged his own field, and the benefits of these excursions into the other’s territory lay more in the insights brought back than in any contribution made on foreign ground.

They collaborated rarely, which may seem surprising given the intensity of their shared worldview and the length of their relationship, some 37 years. But they did have one lasting collaboration: the joint labor of maintaining the household. Despite their different temperaments and commitments to different media (word and image), their worldviews were similar, and what they stood to gain in keeping house together, in addition to intimacy and companionship, was a shared space in which to nourish their shared values.

These values included domestic space as a space of belonging that is generative and must be protected, which Jess called indwelling and Duncan termed the household. They valued the formation of self-made ancestries and collections through acts of accumulation and appropriation. They valued meaning that is multiphasic and in flux. They valued an engagement with fantasy, myth, and romance—Duncan called their life together “story living.”

The house they shared in the Mission district of San Francisco, where most of their life together was spent, physically manifested these qualities. What is immediately apparent about this house is its fullness: a material abundance engrained in an outdated Victorian aesthetic far removed from the clean techno-modernism advertised to housewives in the 1950s, or even the bare functionality of a Coenties Slip loft. “Together, in the early 1950s, Jess and I sought out in our own terms the inspiration of long neglected and even despised sources in 19th-century fantasy,” Duncan explained.

Bookshelves lined almost every room, and several rooms were used as libraries. Their collection contained over 5,000 volumes (as well as 5,300 records) and comprised in-depth holdings in fiction, art history, poetry, literary theory, philosophy, classics, world religion, history, architectural history, biography, fairy tales, science fiction, magic and the occult, Theosophy, drama, psychoanalysis, physics, and biology. Collected authors are too many to name, and ranged from L. Frank Baum to Emily Dickinson, Sigmund Freud, bell hooks, Melanie Klein, Nathaniel Mackey, Plato, Rainer Maria Rilke, and Virginia Woolf.

The wall above Duncan’s desk in his office at 3267 20th Street, San Francisco. Still from Christopher Wagstaff and David Fratto, The Household of Robert Duncan and Jess: An Intimate Portrait of a Legendary Home, 2006. c The Jess Collins Trust.

The wall above Duncan’s desk in his office at 3267 20th Street, San Francisco. Still from Christopher Wagstaff and David Fratto, The Household of Robert Duncan and Jess: An Intimate Portrait of a Legendary Home, 2006. c The Jess Collins Trust.

Artworks covered walls and adorned tabletops. Some of their makers were from the art historical past, like Julia Margaret Cameron, Goya, and Alphonse Mucha, while others were contemporary, such as Conner, Berman, Kitaj, and George Herms. Most remain unknown beyond the Bay Area arts and poetry circles that formed in the 1950s and 1960s, among them Jacobus, Paul Alexander, and Edward Corbett. Work by women artists also appeared throughout the house, like the talented Lyn Brown Brockway, who met Duncan in Berkeley, traveled to Paris with Jay DeFeo, and gave up her painting practice to raise children.

Or Eloise Mixon, who met the couple at Black Mountain College, made sophisticated collages, and wrote multiple unpublished novels before moving with her husband to Australia. In a recuperative gesture, Jess and Duncan populated their home with minor works, from the artworks on walls to the classical music they played constantly.

These collections of things used and displayed in the house represent the couple’s social circle, so that the house becomes an allegory for the household: the repository for the material stuff of their life stands for the couple’s forming a household through careful acts of selection, accumulation, and salvage. These strategies are also integral to each artist’s process, such that the tasks are at once housework and the work of the work. For both men this was a shared project aimed at restoring a sense of belonging by retrieving the neglected, cast-away, and silenced and giving it a home, whether in an image, a poem, or on a shelf.

As Duncan wrote, “for the modern demythologizing mind, our sense of a life shared with the beings of a household, our sense of belonging to generations of spirit, our ancestral pieties, must be put aside.” Household myths, by contrast, spoke “from the realm of lost or hidden truth.” Taking a position that essentially reenacts 19th-century romanticism, whatever they felt could not be thought or valued at a given moment was precisely what Jess and Duncan would stubbornly nurture.

The risks of their process were artworks and poems that could edge into the obtuse and overwrought, the illegibility of the anachronistic. But they persisted in cultivating difference within their household and their work, however much that meant they—like Berman, Helen Adam, Jack Smith, Kenneth Anger, George and Mike Kuchar, and others whose passions were fierce and off-colored and mildly embarrassing—would not fit comfortably, if at all, in canonical narratives of postwar literature and art history.

Both men worked in this home: Jess in his studio on the second floor and Duncan in his office on the third, though Duncan often wrote at the kitchen table. Duncan’s preference for the kitchen table, traditionally a site of women’s work, disavows separating domestic work from the writer’s work. What were the material conditions generated by their household that permitted art and writing to begin at home? Both studio and office, for one, contained constellations of images pinned to walls and objects placed on shelves—a visual scenario one need not be an artist to share.

Jess, Emblems for Robert Duncan II, 6: They were there for they are here. [Two Dicta of William Blake. Roots and Branches.], 1989. Collage, 6. × 5⅝ inches. Tibor de Nagy Gallery. c The Jess Collins Trust.Here were photographs of interlocutors past and present as well as numerous found images and objects that formed highly affective, intimate collages of influence and reflection. Diana Fuss’s words are especially apropos here: “The theatre of composition is not an empty space but a place animated by the artefacts, mementos, machines, books, and furniture that frame any intellectual labour.” For Jess and Duncan, the animations of household gods and self-generated genealogies were integral to their processes.

Jess, Emblems for Robert Duncan II, 6: They were there for they are here. [Two Dicta of William Blake. Roots and Branches.], 1989. Collage, 6. × 5⅝ inches. Tibor de Nagy Gallery. c The Jess Collins Trust.Here were photographs of interlocutors past and present as well as numerous found images and objects that formed highly affective, intimate collages of influence and reflection. Diana Fuss’s words are especially apropos here: “The theatre of composition is not an empty space but a place animated by the artefacts, mementos, machines, books, and furniture that frame any intellectual labour.” For Jess and Duncan, the animations of household gods and self-generated genealogies were integral to their processes.

The wall above Duncan’s desk reads like a visual catalog of the writers whose work preoccupied him and with whom he wrestled his entire life, including Ezra Pound, Charles Olson, Virginia Woolf, and Sigmund Freud. In 1989, soon after Duncan’s death, Jess made a series of 14 Emblems for Robert Duncan to accompany the multivolume publication of Duncan’s collected works by the University of California Press.

One of these emblems is chock full of faces. A young Duncan is in the center. He looks upward, not meeting our gaze. Baudelaire is at his shoulder, or at his ear perhaps, his expression wary and severe. A group in the lower half of the image—Ezra Pound, Walt Whitman, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Gertrude Stein—forms a craggy Mount Rushmore monolith. There are many others present, including Shakespeare, Joyce, Edith Sitwell, and Yeats.

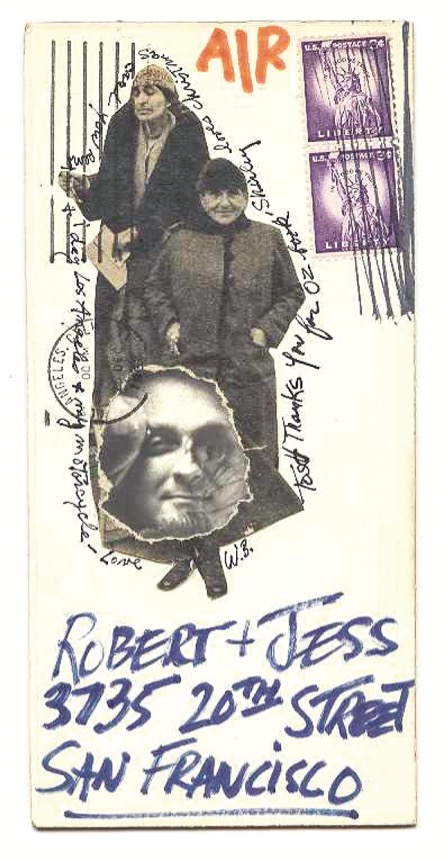

Jess images here the self-generated genealogy, or family romance, that was so central to Duncan’s intellectual life, and which Duncan himself had collaged on the wall above his desk. This visuality of elective association was significant enough to be recognized by Wallace Berman and mirrored back to Duncan as a mode of identification on a slight piece of ephemera, an envelope mailed to Jess and Duncan in 1962 from Los Angeles. On top of a reproduction of Stein and Toklas from a 1934 photograph in which the couple pose on the stairs of a United Airlines flight bound for Chicago, Berman glues a torn photograph of Duncan.

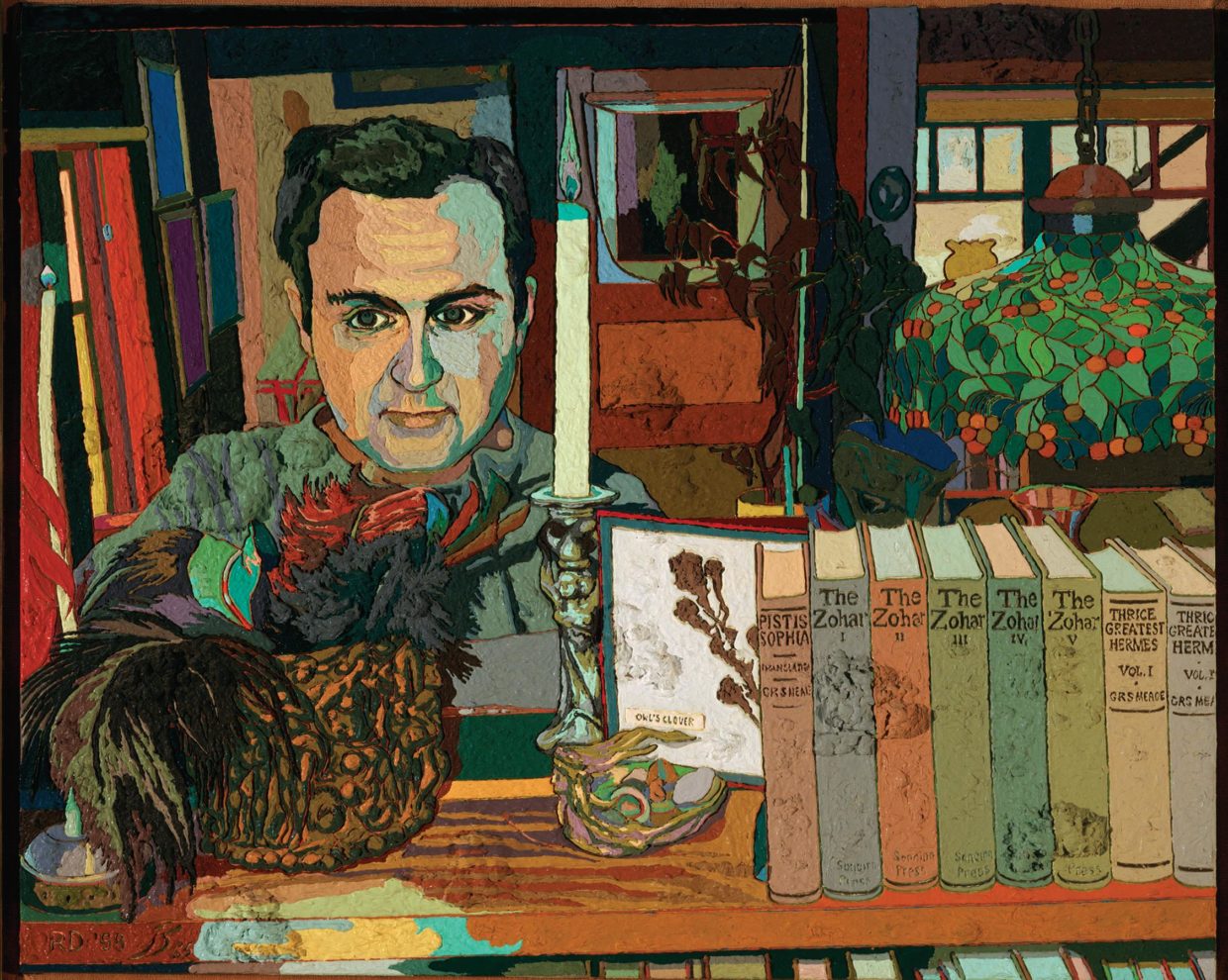

The two women are also excised from their surroundings, so through the medium of collage three bodies now form one mass, the same visual language Jess used for his Rushmoresque emblem. What is striking about the emblem is how crowded it is, suggesting both the intimacy and fullness of the elective family for this “poet of inclusiveness,” in Thom Gunn’s turn of phrase. This is not the only time Jess imparts such a crowded, airless affect to an image of his partner—something similar occurs in The Enamord Mage: Translation #6, 1965, Jess’s most significant portrait of Duncan, and based upon a photograph of Duncan taken by Jess in their home.

Wallace Berman, mailer to Robert Duncan, c. 1962. Ink and collage on card. Courtesy the Estate of Wallace Berman and Kohn Gallery, Los Angeles.

Wallace Berman, mailer to Robert Duncan, c. 1962. Ink and collage on card. Courtesy the Estate of Wallace Berman and Kohn Gallery, Los Angeles.

Academic and stiff, its composition presents no convincing representation of space. Instead, Duncan and his various household objects are pressed up close to the front of the picture plane. The result is a portrait that is as compacted and awkward as it is deliberate and carefully composed—the claustrophobia must be purposeful, since Jess could tease extraordinary depth out of other works.

Duncan’s pin-up on the wall is largely composed of images of people, whereas Jess’s is not. Jess’s entire practice is a process of salvage, so he fills his studio with a sea of images rescued from many sources and many moments in history. Studio photographs show a space full but fairly organized. Tabletops are covered with books and images, and bookshelves are stacked with tools and boxes. In one corner we see Jess’s image drawers—a filing system for visual material collected over the years and arranged by type.

Categories, to give just a few examples, included “Animals,” “Buildings,” “Transportation,” “Vegetation,” and a “Mean Section” subdivided into “Police,” “Bigots,” and “Militarists.” There is an absurd and obsessive quality to this way of ordering the world, as if everything could be neatly labeled and put away in a drawer. Jess’s organizational system speaks to the taxonomic drive of modernism, its attempt, relentless though not without pathos, to order, contain, and know the world, from Aby Warburg’s library to Andre Malraux’s Museum without Walls.

But humor is also present here: in one photograph a plaque proclaims Jess to be a “BEAUTY SPECIALIST.” Nearby is Michelangelo’s David, whose gaze alights on the image Jess has tacked immediately to the right, a reproduction of the 1903 painting Echo and Narcissus by the Pre-Raphaelite John William Waterhouse. In the painting, Echo turns toward Narcissus, but he ignores her, preoccupied as he is with his own reflection. In Jess’s studio, David has been tacked over Echo, so that he takes her place as the figure desiring Narcissus. The transformation of the Narcissus myth into an allegory of male beauty and same-sex desire that Jess undertook in his Narkissos paste-up is thus likewise enacted on the studio wall.

Jess’s studio joined two rooms of the house, the front-facing studio and smaller materials room, but Jess stripped the paint and plaster off the wall between them, so that only the wooden lath framework remained. This physical porosity between the two rooms reinforces a symbolic permeability between Jess’s stores of material and the site of artmaking.

Jess, The Enamord Mage: Translation #6, 1965. Oil on canvas over wood, 24. × 30 inches. Collection of The M. H. de Young Memorial Museum, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. c The Jess Collins Trust.

Jess, The Enamord Mage: Translation #6, 1965. Oil on canvas over wood, 24. × 30 inches. Collection of The M. H. de Young Memorial Museum, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. c The Jess Collins Trust.

At first glance, artwork and studio are nearly impossible to differentiate in these photographs. One wall is a collage of collages, mostly Jess’s own paste-ups, arrayed on a surface that has the character of old paper—water-stained, sepia-toned, cracked and peeling, such that layers of time are revealed on the house’s walls. In the center is Jess’s cover for Michael Davidson’s book of poems, The Mutabilities, published in 1976 by Berkeley’s Sand Dollar Press. And it takes a moment to recognize that at far left is the Narkissos pinboard, so seamlessly does it integrate into the wall’s visual logic.

The pinboard aesthetic, which artists from Robert Rauschenberg to Eduardo Paolozzi adopted in collages made in the 1950s, is usually understood in terms of commodity culture, or as a nod to the visual language of advertising. Things placed on shelves or in rows are like things for sale in the aisles of supermarkets. “Today we collect ads,” Alison and Peter Smithson wrote with delight and desperation (to paraphrase Hal Foster) in 1956. But the pinboard aesthetic, as Jes’s own collection demonstrates, is also a domestic aesthetic, devotional as well as typological, for things have a life after consumption, and are sometime acquired with that life in mind.

Jess and Duncan’s small groupings are closer to the votive corner of a home (Jess called his assemblies “votive objects”), a tenacious religious and cultural tradition stretching back millennia, and one that Malevich exploited to spectacular effect by installing his iconic, and iconoclastic, black square in place of the customary Russian Orthodox icon in 1915.

This sacred devotional space and Jess and Duncan’s affective pinboard collages of found images and elective family portraits are meant to be lived with over time. Alterations and substitutions may be made, but these images come to belong in this space and to this person. They congeal or settle into this space of belonging over time, as eventually would the image fragments in a Jess paste-up, pinned and lived with long before they were glued into place.

__________________________________

Excerpted from The Householders: Robert Duncan and Jess by Tara McDowell (The MIT Press)