A Formidable Writer, An Exceptional Man: Philip Roth on Richard Stern

"His Direct Apprehension of the Real was Amazing"

In memory of Richard Stern.

I met Dick in the fall of 1956, and thus was initiated a 57-year-long literary conversation and friendship. In 1956, Dick had only recently joined the English department of the University of Chicago where I was teaching freshman composition. He was 27, I was 23. I had just returned from the army to Chicago, where I’d earlier received an MA in English. Dick and I started to talk immediately about writers and books and didn’t stop until a week or two before his death.

His assiduous engagement with everything literary never diminished. He was reading fiction, writing fiction, teaching fiction (over the phone to me; in bed with his wife, Alane) right down to the end. For me, as his friend and fellow writer, his appetite for book talk was an inexhaustible treasure.

Dick played an important role, maybe the most important role, in straightening me out when I was first getting going in the mid-’50s. One noon shortly after we’d met as colleagues, we were having hamburgers together at the old University Tavern and, for no purpose other than to amuse him over lunch, I recounted my adventure a few summers back in Jewish suburbia with the dazzling daughter of a prosperous dealer in plate glass. Because Dick was such an eager listener and so enjoyed laughing, I was encouraged to tell the story in all its fullness, embellishing along the way for comic effect.

When lunch was over and we were walking back to campus, Dick said, “Write that, for God’s sake. Write that story.” It hadn’t occurred to me. Write the story of an ephemeral summer romance in inconsequential Maplewood, New Jersey? I wanted to be morally serious like Joseph Conrad. I wanted to exhibit dark knowledge like Faulkner. I wanted to be deep like Dostoyevsky. I wanted to write literature. Instead I took Dick’s advice and wrote Goodbye, Columbus. I would remain responsive to his literary wisdom forever after and would put before him, for him to challenge with his critical vigor, the final draft of virtually everything I wrote.

What did I prize in him? What do I most miss about him? His scrutinizing engrossment with every last vicissitude of existence, his raptness and his rapture, his lucidity, his being perpetually wide awake as if he were being stung by life, his childlike geniality, his gentle and not-so-gentle force, the swiftness of his perspicacity, his impulse to celebrate, his miniscule antipathies and his benevolent urges and his wide-ranging fellow feeling, his imaginative merging with other lives, the bonding of his vulnerability to his fortitude, a steely literary integrity—beyond everything, the way he was weighted down by love. Because the wellspring for his daemonic attentiveness was, in the widest sense, love.

Frequently, while listening to Dick speak of a new colleague, project, sorrow, hardship, idea, improbability, of another blast of news from the great fallen world—while listening to his vivid, focused, unfailingly unhackneyed responses—the same three words would be catalyzed in me: “You’re so human.”

A large, excitable man, highly delighted and of marvelous intelligence, with his face pressed tight to the window.

A man for whom nearly every encounter was unforgettable and for whom fulfillment was no fantasy.

A man who could conceal little and from whom little could be concealed.

His mindful presence here, his joy in being among us, his absorption in everything both within and beyond his ken, seemed never to slacken. Living, for Dick, was an unceasing stimulant and the engagement with life never ceased to evolve. Everywhere this urbane and not entirely unwily man went, mankind flabbergasted and enkindled him. His direct apprehension of the real was amazing.

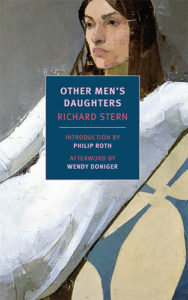

He wrote many wonderful books, beginning in 1960 with the comic gem Golk, a prophetic fable, as it turns out now, more than 50 years later, of the tyranny of mass entertainment and the insidiousness of surveillance. To me his masterpiece is his sixth published novel, Other Men’s Daughters. I’ve reread it twice since Dick’s death. If I may, I’d like to repeat what I wrote about Other Men’s Daughters at the time, in 1973, in the first flush of delightful discovery.

There’s much to admire in this book—the precision, the tact, the humane feeling, the tremendous charm—but what stands out particularly is the intelligent Harvard physiology professor who is (truly) its hero. A blend of restraint, decorum, rampant courtliness and atrophied eroticism, he is a perfect target for the wise and witty Cambridge student-beauty of the Sixties, coutured in jeans and armed with the Pill. And she is his text in the physiology of Love. . . .The theme is Leaving Home, departing the familiar and the cherished for erotic renewal. Richard Stern’s accomplishment (here, as in all his work) is to locate precisely the comedy and the pain of a particular contemporary phenomenon without exaggeration, animus, or operatic ideology. . . . In all, it is as if Chekhov had written Lolita.

Aside from being a novel shapely, penetrating, accessible without being simple in any way, perfect in all its parts and proportions—in its distribution of sympathy, in its graceful narrative jumps as in its artful shifting points of view—Other Men’s Daughters belongs side by side with the strongest of the books that have been written about the historical upheavals and extreme transformations that made so astonishing to the Americans who lived through it the turbulent decade—to be exact, the 11 years—beginning with the shock of President Kennedy’s assassination, extending through the horrors of the Vietnam war, and concluding with the resignation of that most devious of all devious commanders-in-chief, Richard Nixon.

In its modest way—precise and elegant at every turn, no page of prose that isn’t unostentatiously bejeweled and intimately evocative while simultaneously dense with spot-on intelligence—Other Men’s Daughters illuminates a decisive turning point in American mores. The novel reminds us of where we were, morally speaking, when the vast assault upon convention, propriety, and entrenched belief began to challenge authority, high and low, and of the wreckage that caused, the theatrics it fostered, the hope and euphoria and intemperance it quickened. The novel reminds us too of the casualties that were taken by the generation of previously hidebound adults who comprised the first wave to hit the beaches of protean American prudery.

I would contend that in its own felicitous small-scale way, Other Men’s Daughters is to the distinctive character of the ’60s what The Great Gatsby was to the ’20s, The Grapes of Wrath to the ’30s, and Rabbit Is Rich to the seventies: a microscope exactly focused on a definitive specimen of what was once the present American moment.

Golk, Europe, In Any Case, Stitch, Other Men’s Daughters, Natural Shocks, A Father’s Words, Pacific Tremors, exquisitely imagined and surpassingly executed by one of our era’s most distinguished, if unheralded, novelists and men of letters, Richard Stern, who was born in Manhattan on February 25, 1928, and for decades, in the environs of the University of Chicago, lived to the hilt the life of the mind and the imagination (to be sure, tempered, as his biographical record will show, by the daily trials, the inescapable crises, the stunning losses and unavoidable conflicts engendered simply by going about one’s business for eighty-four years) and who, after enduring everyman’s thousand ups and downs, died beside his adoring, brilliant, devoted wife, far from brainy Hyde Park and its renowned university, in his unlikely last home, on little Tybee Island, the easternmost point in Georgia, a very simple place with one main street and a nature sanctuary, on January 24, 2013—a magnanimous friend, a formidable writer, an exceptional man.

__________________________________

From the introduction to Other Men’s Daughters by Richard Stern, by Philip Roth. Copyright © 2016 Philip Roth, used by permission of The Wylie Agency LLC and NYRB Classics.

Philip Roth

Philip Roth is the author of 31 books, including the Pulitzer Prize–winning American Pastoral.