A Fantastical Odyssey Through Renaissance Italy: Álvaro Enrigue on Bomarzo

“Mujica Lainez’s Duke of Bomarzo is a lantern that illuminates... our tenebrous but also brilliant little lives.”

In June 1962 Manuel Mujica Lainez—then fifty-two years old—might have been regarded as a writer past his prime in a country going through a period of brilliance like no other national literature in Latin America has ever seen. On a wet, cold, gray day that austral fall in Buenos Aires, one could see Jorge Luis Borges and Adolfo Bioy Casares having lunch in the Florida Garden restaurant. Two blocks down, at San Martín 689, Victoria Ocampo would be discussing the contents of the next issue of the magazine Sur with José Bianco. (In 1962, Graham Greene, Jean-Paul Sartre, Malcolm Lowry, and Saint-John Perse were among the non-Spanish-speaking contributors.)

In San Telmo, Ernesto Sábato would be having a glass of wine in the Bar Dorrego—maybe satisfied with the critical success of On Heroes and Tombs. Julio Cortázar was not in Buenos Aires in 1962, but in Paris he may well have been dining with Alejandra Pizarnik, as he and Aurora Bernárdez did frequently. Pizarnik had just published Diana’s Tree, and Cortázar’s Hopscotch was soon to roll off the presses. Antonio Di Benedetto, ignored by all because he lived in Mendoza, had already published Zama and was at work on The Silentiary.

In the midst of this experimental writing frenzy, Mujica Lainez must have seemed like a writer looking backward. Before the publication of Bomarzo, he’d been considered a Gallicized realist who’d transplanted the Proustian mode into roman à clef studies of the Argentine criollo elite. His cycle of novels about the children of local patrician families—Los ídolos (1953), La casa (1954), Los viajeros (1955), and Invitados en El Paraíso (1957)—reads today, as it surely did at the time, as a project closer in spirit to the decadence of Huysmans’s À Rebours than the earnest vitalism that could be breathed in Argentina.

Bomarzo, though it seems to meet most of the requirements expected of heavily researched fiction set in the past, is not a historical novel but a fantastical one.

When Bomarzo appeared, Mujica Lainez had not published a book in more than five years. During that time the political map of Latin America, and the world, had taken a Copernican turn: Fidel Castro and his Argentine friend Ernesto “Che” Guevara had secured a previously unimaginable victory in Cuba, and readers were more interested in a new, revolutionary humanity than in the declining last survivors of the aristocracy that had founded, designed, and ruled Argentina—with some populist interruptions—since its independence in 1816.

Yet Bomarzo was a success. It came out under the very prestigious seal of Editorial Sudamericana, won the National Literature Prize of Argentina, and shared the Kennedy Prize with Hopscotch. Whereupon Cortázar fired off a telegram to Mujica Lainez from Paris proposing to make a book together named Bomscotch, maybe Hoparzo. (Not many writers could boast that Cortázar recognized them as equals.) Meanwhile, at a banquet in Buenos Aires, Borges gave a speech comparing Bomarzo to James Joyce’s Ulysses.

The book earned Mujica Lainez the Order of the Merit of the Italian Republic, and it was published in German and English (in Gregory Rabassa’s vigorous translation, reprinted here) at a time when the circulation of Latin American literature in other languages was not at all common. In 1967 the novel was given a second life as an opera—by Alberto Ginastera, with the libretto written in verse by Mujica Lainez himself—which opened to critical acclaim in the Lisner Auditorium in Washington, DC.

Bomarzo has hardly ever been out of print in Spanish and today can be read in the canonical Colección Austral, as well as in a more recent edition brilliantly introduced by Mariana Enríquez, who sees the book as one of Latin America’s contributions to the fantasy genre. The novel, after all, can be read today as an unknowing precursor to Interview with a Vampire or The Rocky Horror Picture Show. It is also a clear antecedent to the explosion of queer literature in the region. It would be hard to imagine the writing of masterpieces like Reinaldo Arenas’s Hallucinations, Sergio Pitol’s El tañido de una flauta (sadly untranslated), or Fernando Vallejo’s Our Lady of the Assassins without the successful circulation of Mujica Lainez’s novel.

*

Bomarzo tells, in first person, the life story of Pier Francesco Orsini from the moment of his birth, when his horoscope predicts eternal life, to his last transit—or whatever it is that happens to those with the Draculaesque gift of immortality. The young Vicino (as his family called him) is second in line to inherit the title of Duke of Bomarzo, but he is the polar opposite of what is expected from a male of his lineage. The Orsini—and this is a historical fact—were a family of condottieri: commanders of private armies that, for a hefty fee, served princes, emperors, and popes. Mercenaries, but of the highest noble condition.

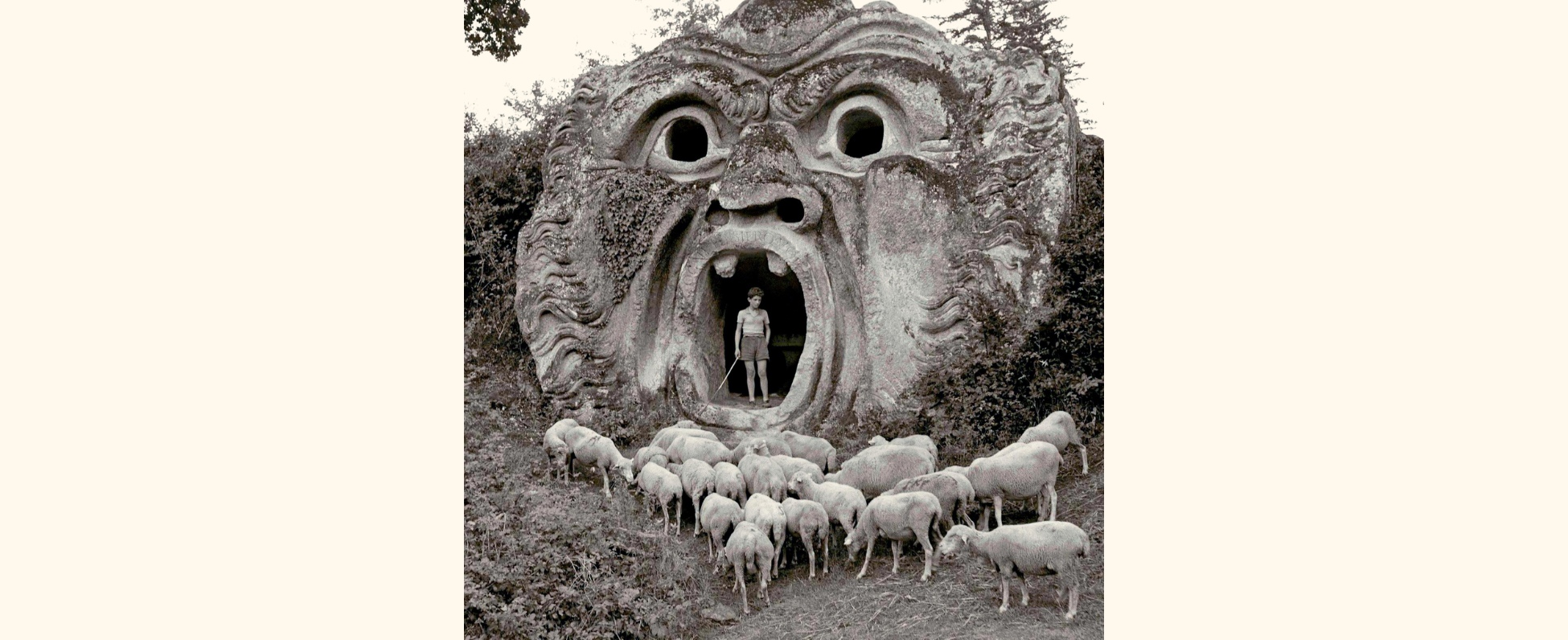

A “hunchback” whose body is ill-adapted to physical action, Vicino has a traumatic childhood. Mocked, bullied, and tormented, he becomes a ruthless politician. When he inherits his father’s title, he uses it to wage war not against other armies but against all conventions, rebelling against everything from normative masculinity to Catholicism to the inevitability of death. The span of his years and the privilege of his parentage allow him to bear witness to such extraordinary events as the coronation of Charles V, the battle of Lepanto, the decadence of the Medici, the rise of the Farnese, and the most glorious hours of the Serene Republic of Venice. As he moves restlessly through Italy, Vicino comes into contact with Giorgio Vasari, Benvenuto Cellini, Lorenzo Lotto, the alchemist Paracelsus, Miguel de Cervantes, and a long lineup of cardinals, popes, and princes who gave us the gift of modern sensibility during those final, convulsive years of the Renaissance. In his retirement, Vicino oversees the design of the dreamlike gardens of Bomarzo—the Sacro Bosco—studded with mannerist sculptures.

Whatever Borges said at the banquet in Buenos Aires was never published, though parts of it seem to have ended up in a note he wrote later about Mujica Lainez’s novel The Wandering Unicorn. Two people, nevertheless, did record their impressions. Bioy Casares, whose dislike for Mujica Lainez ran deep, noted in his journal that Borges’s speech was brilliant. He does not make clear why but notes that the author of “The Aleph” spoke about the influence of Ludovico Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso on modern novels. An anonymous note about the event also appeared in La Nación, written by a harried reporter unaware of the importance of what he saw then for future nerds like us. He tells us that Borges’s comparison of Bomarzo to Ulysses had to do with dimension. Not with the number of pages but with the effort to represent a complete universe in tireless detail, as the great epics do, from The Odyssey to The Aeneid, the Viking sagas and the Arthurian tales, and, of course, Orlando Furioso, which crops up again and again in Bomarzo. All of them are books that contain everything their authors knew about their subject matter—and life.

Mujica Lainez confirms what Borges sensed in a note written at the end of the manuscript of Bomarzo, completed on October 7, 1961. He says that, as empty as he feels at losing the company of Vicino Orsini, and knowing that he would always miss him, “to have finished the novel feels like an enormous relief.” He also says that he will never again write “a novel as vast, as arduous, as demanding as Bomarzo.”

The book was written by an author with a firm, steady hand. The manuscript (and it is truly a manuscript, handwritten from start to finish) begins as the printed novel does, with the horoscope of Pier Francesco Orsini and its strange promise of eternal life. The first attempt—one paragraph—is crossed out. Then come three more false starts, but by the fourth we find ourselves in the novel that would be published three years later. The manuscript fills three notebooks, 708 pages of meticulous longhand. There are crossed-out lines and insertions, but not many.

In addition to the three notebooks that compose the novel itself, there are another seven (hundreds and hundreds of handwritten pages) filled with notes, chronologies, family trees, biographies of every historical character—no matter how small its incidence in the novel—and long critical meditations on the books he read in order to construct the consciousness of Vicino Orsini. The notes devoted to Orlando Furioso could be a short critical book in their own right. Also, of course, there is a handwritten encyclopedia of the influential personalities, noble families, and ruling cities as they existed during the sixteenth century.

Bomarzo is a book full of Italian Renaissance gossip in which most of the characters are who they were historically: popes who were thieves, bishops who fathered many children, princes who were assassins, poets and artists as skilled at their craft as they were at the more complicated art of surviving an era in which the infliction of pain and the desperate rush for power or pleasure had very few moral constraints.

The seventh notebook is composed of additions: sentences and paragraphs, organized by page, to be inserted in the manuscript when it was transcribed on the typewriter. And then there are the notes on the final architecture of the book, which sounds, sometimes, more like a cathedral than like a novel. These notes are the descriptions and personal—and only personal—interpretations of the nineteen sculptures and monuments of the Sacro Bosco of Bomarzo that are the organizing principle of the story, each piece a reference to a plot-changing event in the life of Vicino Orsini. After this narrative map of the Sacro Bosco that is also a map of the novel comes the list of the eleven titles of the book’s eleven chapters.

Yet Bomarzo, though it seems to meet most of the requirements expected of heavily researched fiction set in the past, is not a historical novel but a fantastical one. It is another example of the delicious, if sometimes confusing, freedom that Latin American writers have taken with material from other traditions. It is less that Mujica Lainez had the experimental impulse of Boom writers like Carlos Fuentes, José Donoso, Juan Carlos Onetti, Gabriel García Márquez, and Julio Cortázar, and more, I think, that he was forced to deal with precarity and he did so splendidly.

When, in 1952, Mujica Lainez visited the Sacro Bosco of Bomarzo for the first time, the garden was in a state of abandonment that made it look more like the ruins of a monstrous, extinct civilization than the touristic Renaissance traipse it is today. There is a very accessible film in which Salvador Dalí visits the Park of the Monsters just a few years earlier and its state of abandonment is notorious. The same was true of the biography of the man who designed the garden: it was overgrown with vegetation, and almost nothing was known about him. Mujica Lainez was thus free to imagine a literary Duke of Bomarzo, incarnating the contradictions of his period. A tremendously powerful man who felt like a victim due to his physical disadvantages. A shy, sensitive noble of vulnerable sexuality, but also a cold-blooded murderer and rapist. A man of enormous ambition who could never get over his childhood. A luminous patron of the arts attracted to everything occult, dark, and demonic.

*

It was after the publication of Bomarzo in Italian, and perhaps partly because of it, that the Sacro Bosco became a place of interest not only for tourists but for historians and scholars. Documents lost for almost half a millennium were found: birth and marriage certificates, legal and commercial affidavits, and a good number of letters written by, to, and about Pier Francesco, in the archives of Viterbo (the municipal seat, not far from Bomarzo), as well as in Rome (there were Orsini popes and bishops, and an Orsini palace in the Eternal City) and various academic institutions overseas. (One important collection of letters written by Pier Francesco was discovered in the custody of the University of California in Los Angeles.)

We now know who he was: a very rich and successful condottiere with a taste for earthly pleasures; a man uninclined to the occult and, as far as it is possible to know, to queer practices. We even know how he looked: there is a medal with his portrait in the holdings of the British Museum, which Mujica Lainez never saw and which today anyone can access online. A number of serious critics and excellent readers still assert that he was the model for Lotto’s Portrait of a Young Man, a whimsical touch that Mujica Lainez decided to add after a visit to the Accademia in Venice, where the painting is on display.

Mujica Lainez’s sources were touchingly poor: an issue of Quaderni dell’Istituto di Storia dell’Architettura published in Rome in 1955, the autobiographies of Cellini and Vasari, and an edition of Famiglie celebri italiane published in Milan in 1918. In addition to these few publications, the author also mentioned, in an interview given two decades after the novel first appeared, a topographic study of the Sacro Bosco and a brochure written by the parish priest at the local church. In the same conversation, he confessed that he had visited Bomarzo only twice, and only for one day in both cases: first as a simple tourist in 1952 after reading a newspaper story about the Bosco, and again when he was already writing notes for the novel. On this second trip, thanks to the intercession of the Argentinean ambassador in Rome, he was permitted into the palace of Bomarzo—at the time closed to the public—and the chapel, where he saw the skeleton with a “crown of withered cloth roses” that would become essential to the novel’s plot, one source of the trauma that would make Vicino a stranger to mercy.

The historical character’s adventures, whatever they were, could never be as revealing of the ambiguities and contradictions of the human condition as the mythical Vicino.

Mujica Lainez used to brag, and I find no reason to doubt him, that when the sculptures and paths of the Sacro Bosco were restored and became a frequent stop for visitors to Lazio, the local tourist guides described Pier Francesco Orsini as the bisexual alchemist tormented by an imperfect body that Mujica Lainez had invented in his book. If nothing else, the novel was effective: In his article about visiting Orsini’s “deliberately discordant” gardens, published in The New York Review of Books in 1972, Edmund Wilson bought Mujica Lainez’s version of the hunchback duke hook, line, and sinker.

The biggest influences on the novel, however, are literary. Reading Cellini’s Life in the light of Bomarzo, one gets a bird’s-eye view of Mujica Lainez’s workshop. The naturalness and even lightness with which the Argentinean author describes the brutal life of a man of the cinquecento comes directly from Cellini, who narrates the siege of Rome as if it were a calcio match in which, now and then, some of the players were blown to bits by the enemy’s cannons.

There are also more transparent borrowings. In Cellini’s book, a courtesan named Pantasilea makes a passing appearance. Later, Cellini is invited to a dinner and shows up with a young man dressed as a woman; the courtesan, his lover at the time, is also at the dinner, which leads to an enormously violent scene. In Mujica Lainez’s novel, Cellini tells the same story after dropping a quick, intriguing kiss on Vicino’s young lips. As Bomarzo progresses, Pantasilea grows to monumental proportions, becoming an emblem of the duke’s troubling relationship with sex and beauty. He makes her a grotesque allegory of decayed glamour—a monster—as he does with the stones of his garden, his lovers, and everything else he touches.

Something similar happens with the character of Giulia Farnese, the historical Duchess of Bomarzo. Not much is known about her except that her husband dedicated a temple to her in the Sacro Bosco. Mujica Lainez, nevertheless, appears to take biographical details about her famous great-aunt of the same name—a sister and lover of popes— to produce a magnificent portrait of a serene, resentful duchess in whom all the perversions and servitudes of an esteemed Renaissance lady are carved with believable detail.

This recycling of historical materials, multiplied by the dozens of characters developed in Bomarzo, produces a mimetic effect. The reader spends the days or weeks it takes to finish the novel submerged in an enormous fresco governed by a subtle design in which every major event in the life of the young and brilliant Pier Francesco Orsini finds a bizarre echo in the obscure years during which he constructs his garden. His wedding with Giulia Farnese repeats itself as comedy in the wedding of Pantasilea. The pitch-black moment in which he inherits his father’s title after a series of horrid crimes and dark-arts plots is offset by the luminous coronation of Charles V. His father’s Spartan court turns vaudeville when, in his later years, he becomes a patron of mediocre poets and artists who leech all his money. His second wife, rich and vulgar, is the polar opposite of the first duchess’s distinction, just as Paracelsus’s elegant opacity is a better version of the paltry resident magician and alchemist whom the duke can afford.

In “Odysseus’ Scar,” the imposing first essay of Mimesis, Erich Auerbach proposes that European realism issues from two sources: on the one hand, the very dry telling of biblical stories, in which nothing is visible—no landscapes, no descriptions of characters, no temporal frames—except the action of the main characters; on the other, the Greek epics, in which every detail of every scene and every feature of every character is visible under the zenithal light of Homer’s style. It may have been this second filiation that made Borges think of Bomarzo and Ulysses as consummate examples of a modern epic.

Mujica Lainez’s imaginary Vicino Orsini could not be further removed from his true, historical character. But the historical character’s adventures, whatever they were, could never be as revealing of the ambiguities and contradictions of the human condition as the mythical Vicino—no more than a historical Achilles could achieve the capricious pathos of Homer’s creation. For all its darkness, Mujica Lainez’s Duke of Bomarzo is a lantern that illuminates the place and period that brought us modernity and, as such, our tenebrous but also brilliant little lives.

__________________________________

From Bomarzo by Manuel Mujica Lainez, translated by Gregory Rabassa. Introduction © 2025 Álvaro Enrigue. Available from New York Review Books.

Álvaro Enrigue

Álvaro Enrigue is a writer and editor. His first novel, La muerte de un instalador, won the Joaquín Mortiz Prize in 1996. His second novel, El cementerio de sillas (Lengua de trapo, 2002), was selected as that year's best novel in Spanish by the literary magazine La Tempestad. He has two collections of stories: Virtudes Capitales (Joaquín Mortiz, 1998) and Hipotermia (Anagrama, 2005). He has taught creative writing at the University of Maryland and Latin American literature at the Ibero-American University in Mexico City. Currently, he is an editor at Letras Libres.