Vera Vladimirovna’s final Saturday was a huge success: the coveted poet appeared. The company that evening consisted of the most select lovers of literature, both men and women. These days, it is not at all difficult to get such a group together since literature is extremely respected, and ladies especially have been devoting such attention to it for some time that only by hardly noticeable signs is it possible to guess that, in fact, they play no active part in it.

And so the poet appeared: a shy, rather awkward young man, his gloves not quite fresh. He entered with some feelings of timid pride into the well-lighted and enlightened drawing room where so many important persons, so many beautiful women, had gathered to hear him. But right now, they all had something else on their minds: Vera Vladimirovna’s nephew had unexpectedly brought her a traveler just arrived in Moscow, a Spanish count, terribly interesting, a swarthy proud Carlist with sparkling eyes. Naturally he became the object of general attention, the focus of all female glances, and the focus of the drawing room. All the ladies present were busy trying with fervent effort to please the new arrival, to ingratiate themselves with the foreign visitor by that well-known, incurable hospitality that is sometimes so fond and jealous that it becomes a bit indecent and often makes us appear comical and our foreign guests arrogant. The poor man of letters stood in a corner, completely unnoticed. But what is so surprising in the fact that no one so much as glanced at him in such an unforeseen event? For Moscow ladies, men of letters are nothing unusual, but a Spanish count is still something of a novelty.

But after a couple of hours, the count left, and then the hostess turned her attention to the poet. She went up to him and told him in a very nice way about her own and everyone else’s impatience for and expectation of the recital he had promised. Then she seated him by a table with the audience around him, herself magnanimously occupying the most prominent place nearest him, where it would be impossible either to whisper or to yawn. The poor young man was a bit troubled and began to turn the pages of his notebook, not knowing what to select from it. Everything he did made it clear that it was the first time that he was preparing to deal with this class of people, who are separated from the rest of humanity and compose that haughty fashionable “world,” as it is so naively called, for which no other world exists in the Lord’s universe.

Because Cecily and other young ladies were there, the recital had to be completely moral and blameless, and the timid poet, after some hesitation, finally decided to read his unpublished translation of Schiller’s “Bell.” He coughed and said in a modest voice, “The Song of the Bell.” A minute’s silence followed, a few graceful heads leaned forward, some rosy lips smiled sweetly, some lovely listeners fixed affable looks upon the young poet while making a mental note that this was a very long piece. Emboldened by such flattering attention, the young man began to read, at first in a soft voice, then in a louder and livelier one. He was so young and inexperienced that he read his verse before that aristocratic society with the same passion with which he spoke them alone to himself in his modest room. He was so tempered in the flame of poetry that he did not sense the worldly coldness of all these people. He placed before them a series of magically changing views: a peaceful childhood, a stormy youth and the ecstasy of love, quiet happiness, grief come from heaven, the flame of fire, the gloom of devastation and a mother’s death, and then, in the distance, meadows in the light of evening with the herds slowly returning, the night quietly falling, healing calm and sudden, terrible restlessness, the joys of life and the sorrows, ringing forth in the prayerful, fateful sound of the bell, and finally, from his burning lips, the last inspired words flew:

And henceforth may this be

Its destiny

Amid the heavens’ expanse

Carried high above Earth,

May it float, near to thunder

And approach the world of stars.

May its holy voice come from on high

Like all the constellation’s choir

May it praise the universe-creator

And bring along a generous year.

May it proclaim with bronze tongue

Only that which is sacred and omnipotent;

May the wing of time beat within it

Every hour as it goes by.

And may it be the word of fate,

Standing unconsciously above all,

May it herald from afar

The game of Earth’s reality,

And startling us from on high

With powerful sounds,

May it teach us that all is not eternal,

That all things earthly will pass.

The notebook fell from his hands. He fell silent.

“C’est délicieux! C’est charmant!” whispered a few voices.

Vera Vladimirovna repeated, with emotion, “C’est charmant!” and thanked the poet for the pleasure he had given them.

“How fine that was,” said Cecily into Olga’s ear.

“Very good,” Olga replied, looking intently at someone through her lorgnette.

A short silence ensued.

“Yes,” said a short, sweetly smiling little man of about fifty, “that thought about time is a very felicitous one, but a bit drawn out in the German manner. With what strength and compression Jean-Baptiste Rousseau managed to express it in two lines:

Le temps, cette image mobile

De l’immobile Eternité.”

One lady among the charming neighbors of the man of letters leaned close to him and asked sympathetically, “How long did this marvelous translation take you?”

“I don’t know,” answered the poor, confused young man.

She turned away with a barely perceptible smile.

“That is really good poetry,” said a lean, serious man, Prince Somebody, quietly sitting in a large armchair, “but it’s . . .” (he stopped for a moment, took a pinch of snuff, stretched his right leg over his left, and continued) “but it’s not very contemporary poetry. We are not content any more with empty dreaming; we demand action. In our century, a poet should labor alongside this hardworking generation; poetry should be useful; it should hold vice up to shame or set a crown on virtue.”

Vera Vladimirovna stood up for Schiller.

“Permit me, Prince,” she remarked, “it seems to me that you are not quite right about the poem; there is much that is morally edifying and truly useful in it.”

“Yes,” interrupted the prince, inflamed by his own eloquence, “but it is all somehow not alive enough, not expressive enough. We want to see the point of a poem clearly. Understand this,” he continued, turning to the poet, “your noble calling is more important now than ever, morally higher. Write poetry against cold-hearted egotists, against the debauches of flighty young people, stir the conscience of the evildoer, and then you will be a contemporary poet. We recognize only what is useful to mankind.”

The poor young poet thought for a moment, perhaps, that to feel and to reason, to love and to pray—this too might be somewhat useful for humanity; but he was silent.

__________________________________

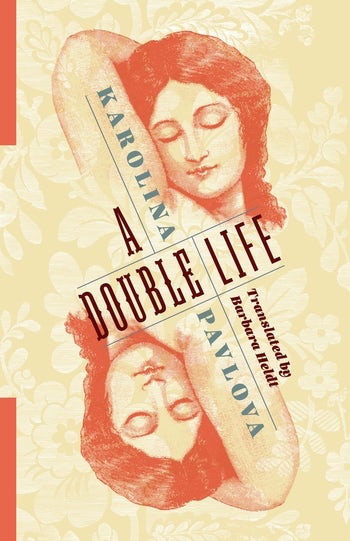

From A Double Life by Karolina Pavlova, translated by Barbara Heldt. Used with the permission of the publisher, Columbia University Press. Copyright © 2019 by Barbara Heldt.