A Century of Reading: The 10 Books That Defined the 1920s

Part Three of Your New Favorite Series

Some books are flashes in the pan, read for entertainment and then left on a bus seat for the next lucky person to pick up and enjoy, forgotten by most after their season has passed. Others stick around, are read and re-read, are taught and discussed. sometimes due to great artistry, sometimes due to luck, and sometimes because they manage to recognize and capture some element of the culture of the time.

In the moment, you often can’t tell which books are which. The Great Gatsby wasn’t a bestseller upon its release, but we now see it as emblematic of a certain American sensibility in the 1920s. Of course, hindsight can also distort the senses; the canon looms and obscures. Still, over the next weeks, we’ll be publishing a list a day, each one attempting to define a discrete decade, starting with the 1900s (as you’ve no doubt guessed by now) and counting down until we get to the (nearly complete) 2010s.

Though the books on these lists need not be American in origin, I am looking for books that evoke some aspect of American life, actual or intellectual, in each decade—a global lens would require a much longer list. And of course, varied and complex as it is, there’s no list that could truly define American life over ten or any number of years, so I do not make any claim on exhaustiveness. I’ve simply selected books that, if read together, would give a fair picture of the landscape of literary culture for that decade—both as it was and as it is remembered. Finally, two process notes: I’ve limited myself to one book for author over the entire 12-part list, so you may see certain works skipped over in favor of others, even if both are important (for instance, I ignored Dubliners yesterday so I could include Ulysses today), and in the case of translated work, I’ll be using the date of the English translation, for obvious reasons.

For our third installment, below you’ll find 10 books that defined the third decade of the 1900s—a decade that, as you may notice, the literary world is still particularly obsessed with.

Agatha Christie, The Mysterious Affair at Styles (1920)

Agatha Christie, The Mysterious Affair at Styles (1920)

Christie’s first published novel—and the first to feature her mega-famous creation Hercule Poirot—was released to wide acclaim (somewhat surprised acclaim, considering it was a first novel by an unknown) in 1920, helping to usher in the Golden Age of Detective Fiction, not to mention the enduring love affair that millions of fans would have with Christie’s work. According to the flap copy of the first edition, Christie wrote it after accepting a bet—that she couldn’t write a mystery novel in which the reader could spot the murderer before the detective. Everyone agrees that she won. Now she’s one of the best selling, widely translated, and most influential novelists of all time—but it all started here.

T. S. Eliot, The Waste Land (1922)

T. S. Eliot, The Waste Land (1922)

Eliot’s masterpiece is widely considered to be one of the most important works of Modernist literature, not to mention 20th-century literature in general. The book-length poem, which Louis Menand describes as “a collage of allusion, quotation, echo, appropriation, pastiche, imitation, and ventriloquism,” but also “a report on the condition of postwar Europe,” didn’t sell particularly well (330 copies in the first six months), but the Cambridge academics seized upon it, and with Eliot’s other works, used it as the basis for creating the modern English department.

James Joyce, Ulysses (1922)

James Joyce, Ulysses (1922)

If we’re counting by literary influence, Ulysses was biggest book of the 20s by far—the most important Modernist text and certainly one of the most important novels ever written. “Ulysses,” T. S. Eliot told Virginia Woolf, “destroyed the whole of the 19th century. It left Joyce himself with nothing to write another book on. It showed up the futility of all the English styles.” For her part, Woolf wasn’t always convinced, but did sing its praises in her essay “Modern Fiction,” calling it “undeniably important . . . The scene in the cemetery, for instance, with its brilliancy, its sordidity, its incoherence, its sudden lightning flashes of significance, does undoubtedly come so close to the quick of the mind that, on a first reading at any rate, it is difficult not to acclaim a masterpiece. If we want life itself, here surely we have it.”

Marcel Proust, Swann’s Way (1922)

Marcel Proust, Swann’s Way (1922)

If any book could challenge Ulysses for the top spot in literary history, it’s Proust’s seven-volume masterpiece about memory, In Search of Lost Time, the first book of which was translated by C. K. Scott Moncrieff and published in English for the first time in 1922. In fact, in 2013 Edmund White called it “the most respected novel of the 20th century,” and noted that “in the last 30 years Proust has superseded Joyce.” Either way, like Ulysses, it is a widely influential, much-discussed, probably under-read, classic exemplar of the decade in literature, a text that reverberates through to much of our art today.

Jean Toomer, Cane (1923)

Jean Toomer, Cane (1923)

Yet another Modernist masterpiece for this list, this one also a significant text of the Harlem Renaissance, notable for its experimental style, which blends poetry, prose, and drama to illuminate the lives of African Americans living under Jim Crow. Though it received positive—if sometimes baffled—reviews from contemporary critics, the book did not find widespread success in the decade of its publication. “The Negro artist works against an undertow of sharp criticism and misunderstanding from his own group and unintentional bribes from the whites,” wrote Langston Hughes in his 1926 essay “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain.”

“Oh, be respectable, write about nice people, show how good we are,” say the Negroes. “Be stereotyped, don’t go too far, don’t shatter our illusions about you, don’t amuse us too seriously. We will pay you,” say the whites. Both would have told Jean Toomer not to write Cane. The colored people did not praise it. The white people did not buy it. Most of the colored people who did read Cane hate it. They are afraid of it. Although the critics gave it good reviews the public remained indifferent. Yet (excepting the work of Du Bois) Cane contains the finest prose written by a Negro in America. And like the singing of Robeson, it is truly racial.

Now it’s considered one of the most important books of the Harlem Renaissance, and a Modernist classic, particularly notable for its formal flexibility and enduring influence on later works.

F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby (1925)

F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby (1925)

Given its enduring cultural relevance, it’s impossible to ignore this Great American Novel, and its influence on the way we imagine the 1920s in this country, despite the fact that in the actual 1920s, it wasn’t considered so great. Sure, readers loved This Side of Paradise and The Beautiful and the Damned, but The Great Gatsby represented something of a fall from grace. “Fitzgerald’s Latest A Dud” read the headline of a review in the New York World. Other reviewers were less critical but unenthusiastic, and by the time Fitzgerald died in 1940, the book had sold fewer than 25,000 copies. Now it sells 500,000 copies a year, if mostly to disgruntled students. It was WWII that rescued Gatsby from obscurity. The US government developed a program to send cheap paperback books to soldiers, and of the 1,227 titles chosen, one of them was The Great Gatsby. The program was wildly popular—by some estimates more than a million soldiers read the novel—and Fitzgerald’s reputation soared. It hasn’t slowed down yet.

Virginia Woolf, Mrs. Dalloway (1925)

Virginia Woolf, Mrs. Dalloway (1925)

You could argue (or at least I would) that To the Lighthouse (1927) is the more formally exciting—and even the better—book, that Orlando (1928) is decidedly more fun, and that A Room of One’s Own (1929) is the most widely and continually influential (or at least glibly quoted) but I think it’s safe to say that Mrs. Dalloway is the most loved. At least, that’s my read after surveying the Literary Hub office, the internet, and the members of my own personal family. It was also very well regarded in its time—in a contemporary review in the New York Times, John W. Crawford wrote:

Among Mrs. Woolf’s contemporaries, there are not a few who have brought to the traditional forms of fiction, and the stated modes of writing, idioms which cannot but enlarge the resources of speech and the uses of narrative. Virginia Woolf is almost alone, however, in the intricate yet clear art of her composition. . . . Clarissa is . . . conceived so brilliantly, dimensioned so thoroughly and documented so absolutely that her type, in the words of Constantin Stanislavsky, might be said to have been done ”inviolably and for all time.”

Despite all the competition, Mrs. Dalloway is a standout work in a standout career, a hallmark of the Modernist movement, and a splendid, wrenching, subtle psychological novel, beloved in its day and beloved now.

Langston Hughes, The Weary Blues (1926)

Langston Hughes, The Weary Blues (1926)

The title poem of Langston Hughes’ first collection is still one of his most famous, weaving language and jazz together as in all the best of his work, and he’s probably the most important figure of the Harlem Renaissance. “It’s the poems that speak of being “Black like me”—black still being fighting words in some quarters—that prove especially moving,” wrote Kevin Young in an introduction to a 2014 edition of the book.

Hughes manages remarkably to take Whitman’s American “I” and write himself into it. After labeling the final section “Our Land,” the volume ends with one of the more memorable lines of the century, almost an anthem: “I, too, am America.”

Offering up a series of “Dream Variations,” as one section is called, Hughes, it becomes clear, is celebrating, critiquing, and completing the American dream, that desire for equality or at least opportunity. But his America takes in the Americas—including Mexico, where his estranged father moved to flee the color line of the United States—and even the West Coast of Africa, which he’d also visited. His well-paced poetry is laced with an impeccable exile.

A groundbreaking collection from an iconic American artist.

Ernest Hemingway, The Sun Also Rises (1926)

Ernest Hemingway, The Sun Also Rises (1926)

Hemingway’s outsize influence and literary fame began with the publication of The Sun Also Rises, his first proper novel, and hasn’t abated much in the 90 years since. “No amount of analysis can convey the quality of The Sun Also Rises,” the New York Times purred in the year of its release.

It is a truly gripping story, told in a lean, hard, athletic narrative prose that puts more literary English to shame. Mr. Hemingway knows how not only to make words be specific but how to arrange a collection of words which shall betray a great deal more than is to be found in the individual parts. It is magnificent writing, filled with that organic action which gives a compelling picture of character. This novel is unquestionably one of the events of an unusually rich year in literature.

In the years after, some writers would diligently copy his sparse, “athletic” prose, and others would fly descriptively in the opposite direction, but almost everyone would develop an opinion on him, and at least some degree of knowledge of him. He’s still, decades after his death, as beloved a literary celebrity as he was during his lifetime.

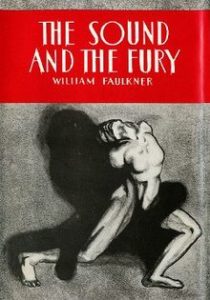

William Faulkner, The Sound and the Fury (1929)

William Faulkner, The Sound and the Fury (1929)

We’ll round out this gutting (for me—I’ve had to cut so many!) list of literary giants with everyone’s least favorite postman, whose stream-of-consciousness masterpiece is one of the most difficult, important, complex, and lionized works of American literature—our best, not-so-humble contribution to the High Modernist era. Faulkner won the 1949 Nobel Prize for Literature for “his powerful and artistically unique contribution to the modern American novel.”

See also: D. H. Lawrence, Women in Love (1920), Edith Wharton, The Age of Innocence (1920), F. Scott Fitzgerald, This Side of Paradise (1920), Sinclair Lewis, Main Street (1920), Albert Einstein, The Meaning of Relativity (1922), Emily Post, Etiquette (1922), F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Beautiful and the Damned (1922), Katherine Mansfield, The Garden Party (1922), Margery Williams, The Velveteen Rabbit (1922), William Carlos Williams, Spring and All (1923), Carrie Chapman Catt and Nettie Rogers Shuler, Woman Suffrage and Politics: The Inner Story of the Suffrage Movement (1923), Robert Frost, New Hampshire (1923), Emma Goldman, My Disillusionment with Russia (1924), Thomas Mann, The Magic Mountain (1924), E. M. Forster, A Passage to India (1924), Herman Melville, Billy Budd, Sailor (1924), Theodore Dreiser, An American Tragedy (1925), Alain Locke, ed., The New Negro (1925), Anita Loos, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1925), A. A. Milne, Winnie-the-Pooh (1926), Thornton Wilder, Bridge of San Luis Rey (1927), Willa Cather, Death Comes for the Archbishop (1927), Virginia Woolf, To the Lighthouse (1927), Virginia Woolf, Orlando (1928), Aldous Huxley, Point Counter Point (1928), Evelyn Waugh, Decline and Fall (1928), Dashiell Hammett, Red Harvest (1929), Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own (1929), Thomas Wolfe, Look Homeward, Angel (1929), Henry Green, Living (1929), Ernest Hemingway, A Farewell to Arms (1929), Erich Maria Remarque, All Quiet on the Western Front (1929), Nella Larsen, Passing (1929), etc.

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.