A Brutal—and True—Piece of Writing Advice from Toni Morrison

A. J. Verdelle Recalls a Memorable Q&A with an Iconic Writer

The very first time I saw Toni Morrison in person was at an event in Boston, at a church, along with hundreds of people. The Beloved tour. I attended as a reader, as a Morrison fan. I’d had plenty of reader-only experience with books, but I knew next to nothing formal about writing then. Reading as a writer is a higher calling, and a whole different world. I had no writing tools at the time, though I did have some facility; I loved words—but the tools you need to write stack up and can be complicated. I could identify and define imagination, but I did not know the concepts of setting or drama or scene. I knew that language was critical, but how few words I knew then! I was hungry, eager, reaching—but I was ignorant of exactly what writers needed to know and do.

I was working as a statistician in the social sciences at the time. I consulted with clients who needed numbers turned into measurable questions. We’d create the questions, collect the data, and then turn those numbers back into words. I liked my work sufficiently, but I was a writer in corporate dress.

The Boston church was large, a fairly cavernous sanctuary, and packed. My awed memory estimates eight hundred in attendance. People sat close together, many of them women, with their pictureless copies of Beloved clutched in their hands, sometimes held to their hearts. Microphones waited vacantly for Morrison to complete her presentation, invitations at the top of aisles for the coming Q&A. While Morrison read, but for the sanctuary carpet, you could have heard the proverbial pin drop.

Beloved is a difficult read, especially the first time. The novel had not been out long by that evening. This was before it had been widely read, or deeply discussed, or passed from hand to hand, or canonized. Not having yet read it, we were mostly mystified by what the novel laid bare, but mesmerized by the woman who stood before us, who—the reviews of Beloved told us—had created yet another powerful, riveting narrative meditation on the depths and pressures of our American experience.

From her earlier novels, we knew that Toni Morrison put Black women in novels in gowns and crowns, with lithe flexibility, with the most nuanced and frenetic lives. Morrison wrote about Black women as if we were real, and important, and conflicted, and brainy, and righteous, and determined, and unafraid of running off. Beloved flowed from the ascendant to the enraged to the elegiac to the frightening to the rueful to the anticipated to the outraged to the treacherous; from past to future, through the netherworld.

The past was Morrison’s landscape. Though we lived in the present tense, we were the future of the past. She gave us our history without sugar or disdain, and through her work, we watched ourselves struggle and survive. She did use pretty language, but pretty is not sugar; her words lean—tough, pointed, and sometimes mean. You were caught when you read Morrison. It was impossible to read and look away.

Back there, back then, in Boston, the book I held in my hand in that sanctuary positively shook with mystery. Long before the event, I had loaned my copy to an old friend who also attended that day; she had wanted to read the book right away. Because I knew I needed the time and space to work with the novel, I had agreed, but I insisted that she not wreck my copy, especially not the dust jacket. A clean, intact dust jacket gives a hardcover value over time. My silly friend took the dust jacket off to protect the dust jacket—per my instructions, she said—and then sullied the actual cloth cover of the book with lipstick and cereal, both unhealthy substances for books. My friend was alarmed by my alarm. “You said the dust jacket needed to be clean!” she said. “I kept the dust jacket clean!”

“Well, it sounds like you don’t know what you’re doing,” Morrison began.

In time, in life, you learn that you have to be specific, explicit, sometimes almost stupidly blunt. Or, you have to not lend people books. I lend books. I want people to read. My library is a thousand books deep. Too much power there to be selfish and grabby. However, to be clear, the dust jacket is important to a hardcover book’s value over time. A hardcover without a dust jacket may as well be an airport paperback. That said, the book under the dust jacket should be kept clean, too. Liquids and lipstick are bad for books. I hold esteem for books.

*

Morrison read from the novel with her husky voice and Black woman’s authority. She was an author among us, a higher-up, a guiding light. Many of us in attendance had read her other books; that was how I knew I was going to need time with this one. The passage she read from Beloved that day did not disabuse me of that notion. Even if we’ve never read a book in our lives, every one of us has a read on slavery. Morrison’s manner of spearing history with her sharpened pencil in previous books made me know I’d likely be slayed by Beloved and that the time for that would need to be carefully arranged. I was in no rush.

During the Q&A, one young woman made her way to the microphone to ask one of the earliest questions. She might have been the first in line, with the first question. In my memory, she rushed her speech; she may have been breathlessly waiting. She described her interest in writing, her aspirations, and her failure to accomplish the fiction she aimed for. She described her struggle with making her stories “just right.” Likely trying to be succinct and yet communicate directly with the greatest of writers, she sounded hurried, even as she sought direction. She then joined the rest of us in silence, to hear what Morrison advised.

“Well, it sounds like you don’t know what you’re doing,” Morrison began.

Quiet in the sanctuary. I drew in my breath. The huge audience almost gasped in unison. I remember the hiccup of my own heartbeat; the whole scene went instantly wavy before my eyes.

My anxiety pounded in my ears, which made hearing hard. My embarrassment for her echoed and bounced around the chambers of my mind.

I empathized: I understood not knowing what to do. But I would not have asked the great Ms. Morrison such a question—so nakedly personal, and too particular to be answerable, really. Especially over the heads of hundreds. And in front of God and everybody. And in such a public space. And when the great writer was expecting to be asked about her own masterful novel—just published, just read from, the whole reason for the tour.

Narcissism can cause mistakes. What could Toni Morrison possibly know about that woman’s struggles with her own blank page? Not knowing the definition of complete self-absorption can make you foolish in the context of community. The young woman might have obtained a different or better response if she had asked a writing question about the author’s work. She could have asked about her own writing under cover:

Ms. Morrison, how do you make the impossible believable?

Ms. Morrison, how do you get your characters so tied to the invented place?

Ms. Morrison, what are the best strategies for research?

Or, even, What writing suggestions do you have for an aspiring writer, for a dreamer like me?

I slid down, trying to hide, mortified and wanting to be invisible for the young woman who had asked the ill-considered question. The spirit in me, the spunkette, the woman who wanted to know what Toni Morrison did and thought, harbored a hungry curiosity over how this would turn out, but I couldn’t help but dream of a hole opening up to swallow the awkwardness.

You don’t know what you’re doing. Morrison did say this aloud.

I don’t, I thought to myself, as if this were my conversation. You’re right. I have no idea what I’m doing. What am I even thinking?

All these years, Morrison’s first spoken sentence (from the first time I remember seeing her), her whip of a reply, has stayed with me.

Who did that reaching aspiring writer think she was? To be so personal, publicly? Showing all she didn’t know? And now likely having to slink back to her seat in that crowded church, having been told off or, more benevolently, told to practice and learn—and by Toni Morrison. This was a public event, so, relatively quickly, the line for the microphone shifted. The aspiring writer left the mic; I could not see the exit well. Maybe the questioner walked straight out the sanctuary doors. That is what I might have done.

I, too, worried about whether I understood the terms of writing. I had not yet begun to write seriously or in form. I had pages of words, observations of my little travels, my tiny thoughts. Occasional poems. But books and long stories need shape and scaffolding. It takes knowledge, experience, study, apprenticeship. It takes architecture.

This young woman needed the basics. Morrison continued, pointing her, and us, toward some fundamentals:

You need to study what writing requires. And:

Writing has rules, conventions, requirements. There is form. And:

Writing is more than your thoughts about characters. Drama has structure. You can learn.

That nameless young woman who had scurried to be first at the mic prepared me for what I did not know my future would bring: stinging quips and side-eye admonishment from the greatest living writer. All these years, Morrison’s first spoken sentence (from the first time I remember seeing her), her whip of a reply, has stayed with me. In that huge sanctuary, I felt personally stung, even if only empathetically.

You don’t know what you’re doing. Yes, this is true.

Yowzah and ouch!

__________________________________

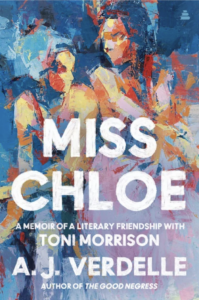

Excerpted from Miss Chloe: A Memoir of a Literary Friendship with Toni Morrison by A. J. Verdelle. Published by Amistad. Copyright © 2022 HarperCollins.

A. J. Verdelle

A. J. Verdelle is an award-winning novelist and essayist. She is a recipient of a Whiting Writer’s Award and teaches in the low-residency MFA program at Lesley University, and teaches undergraduates at Morgan State University. She remains a working mother, and feels confident that the western, Genuine Cowboy, will eventually have a life in print.