A Brief History of the New York Times Wedding Announcements

Cate Doty on the Evolution of a Society Mainstay

The first piece of content that can be identified as a wedding announcement appeared in the New-York Daily Times on September 18, 1851. “In Trinity Church, Fredonia, on the 15th, inst., by Rev. T.P. Tyler, JOHN M. GRANT, Esq., of Jamestown, to SARAH, daughter of Hon. JAMES MULLETT of Fredonia.” In that same edition, the governor of Pennsylvania empowered his fellow citizens to help capture enslaved Black people who had crossed the border into Maryland and who had, in the course of protecting dozens of other fugitives who had holed up in a barn, shot and killed two of the enslavers in pursuit, who went by the name of Gorsuch. The paper also declared that George P. Putnam would soon be publishing The Book of Home Beauty by Mrs. Kirkland, complete with “twelve elegantly engraved Female Portraits,” and that “A Bloomer Costume,” otherwise known as a woman wearing pants, had made an appearance on 6th Avenue two days before, but had been faced by a group of self-described Conservatives, who had manifested their hostility toward such a progressive movement. This was where Sarah Mullett and John M. Grant, Esq., pledged their troth: a young America with the manners of a preschooler and the morals of a pawn broker, where enslaved people faced charges of treason for just trying to get free, and where anyone who was not a white man faced diminution and disregard.

By 1865, as many as twenty couples an issue submitted their matrimonial announcements to the Times, which, as with the notice for the Grants, gave only the barest of details. These were the plebeians, however—those who did not live on Washington Square. For at least 25 years, newspapers had already been in the practice of reporting and writing about society and royal weddings, the details of which set trends for years and decades to come. Take, for example, Queen Victoria’s 1840 wedding to Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. British newspapers breathlessly reported the details of her sumptuous wedding, including a three-hundred-pound wedding cake, and more important, her cream satin dress embellished with Honiton lace and orange blossoms. Before then, most women chose colored wedding dresses, and those who wore white at all were known to have the money and wherewithal to keep their white clothing clean. Through the power and reach of the press, Victoria changed all that, influencing women across the decades and centuries to choose white or cream for their wedding dress, and it had nothing to do with bridal purity.

Over the 19th century, reports of weddings, parties, and social affairs became more entrenched in what newspapers were expected to provide their readers. By the 1880s, society journalism was well established, and society reporters thronged every major bridal event in New York. While old-line society families may have feigned horror at the infiltration of the dirty masses into their well-protected enclaves, they needed that publicity to keep power. The write-ups of society weddings were, on their surface, details of wedding parties, veils, trousseaus from Paris, and wedding tours to the Riviera. But what they really signaled was a family merger: a connection made legal in the eyes of the church, and state, that consolidated social, political, and academic power between families.

Consider, for example, the 1880 wedding of Miss Mary Virginia Smith, known as Jennie, to Fernando Yznaga. Miss Smith’s sister, the former Alva Erskine Smith, was married to William Kissam Vanderbilt, a grandson of Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt, whose father, William Henry Vanderbilt, in 1877, became the richest American after he took over the Commodore’s fortune. (At this point, the Vanderbilts were still considered interlopers by New York’s upper crust, although they were fast on their way to being as rich as Croesus and as powerful as any Astor. In fact, when Caroline Schermerhorn Astor died, Alva, who by that point had dropped the Vanderbilt and married a Belmont, took her place as one of the leaders of the Four Hundred, Ward McAllister’s list of the people in New York society who really mattered.) Fernando Yznaga, quite the man about town, was a Cuban sugar heir who knew what he was doing. Right after he married Miss Smith, he was awarded a seat on the New York Stock Exchange and a big job with a big banking firm—“Presto!” noted the Times. And even after they divorced six years later, he stayed close enough with Vanderbilt to be considered part of the “Three Vanderbilt Musketeers,” a fact that was mentioned with no small amount of pride in his obituary in 1901, after he died of diphtheria. Anyway, the Smith women knew what they were doing too. Upon the occasion of Jennie’s second marriage, to a cousin of Louis Comfort Tiffany, the Times had this to say: “It is understood that Mr. Yznaga settled a handsome income on the bride of yesterday, but she will not need this, as Mr. Tiffany is an exceedingly wealthy man.”

For decades and centuries, people—women, really—have established, gained, and consolidated power through marriage, and wedding announcements bear that out.

Is that news? Not really. Is it gossip? Absolutely. For decades and centuries, people—women, really—have established, gained, and consolidated power through marriage, and wedding announcements bear that out. Edith Wharton knew that gossip was and is power, and those who hold the most knowledge hold the strings of power. Understanding bank balances and legal this-and-that is important, to be sure—but families are made and destroyed by the stories we tell, and wedding announcements are no different. Which brings me to my other point: even though New York society families may have eschewed these write-ups in private, they used them to publicly signal where their money was going and what their priorities were. In The Age of Innocence, May Welland’s mother might have been horrified to know that reporters would be gathered just outside the church awning, to report on May’s Parisian bridal gown and who among the blue bloods was in attendance. But those selfsame bluebloods were rapidly, furtively using the press—behind drawing room doors and in public—to further their own interests.

Of course, times are different now. But they aren’t that different. The Times wedding announcements are signalers not just of social class but of intellectual and economic achievement. The du Ponts and Rockefellers still pop up occasionally, but for the most part, the pages are filled with a new guard of American society: still pretty white, but way more Jewish and far less straight than they used to be. David Brooks wrote a lot about this in his book Bobos in Paradise: since the Gilded Age, the pages, and the announcements, have traced the evolution of America’s ruling class from a consolidation among a hundred or so ruling families, to an ambitious establishment created by those who have gained entry on merit.

Well, sort of. Merit is as merit does. The announcements largely feature white upper-middle-class people, which means, of course, that they were born with at least one leg up. I will tell you that I can count on one hand the number of Black couples that I wrote about during my tenure on the desk, despite Ira’s attempts to reach out to Black churches and community groups. This was a historical failing and not one that had improved much with time. The Times did manage to cover the nuptials of Ida B. Wells, the anti-lynching journalist who the newspaper’s editorial writers, seeking to justify lynching just the year before, had called “a slanderous and nasty-minded mulatress.” Her wedding in Chicago to Ferdinand L. Barnett, “a local colored attorney of prominence,” warranted a notice on the front page of the edition of June 28, 1895. It was a remarkable development for a Black woman born into enslavement and who was herself, as Nikole Hannah-Jones later noted in the Times, “by definition, remarkable.” The nine-line item abutted another bit of society news: the second wife of Fernando Yznaga, the former Mabel Elizabeth Wright, was holed up with her artist father in Yankton, South Dakota, and seeking a divorce.

__________________________________________

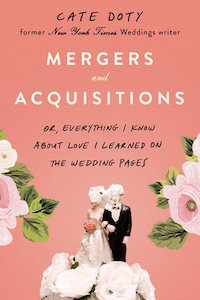

From MERGERS AND ACQUISITIONS by Cate Doty, published by Putnam, an imprint of The Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2021 by Mary Catherine Doty.

Cate Doty

Cate Doty is a writer and a former editor at The New York Times, where she worked for nearly 15 years, including as a wedding announcements writer, presidential campaign reporter, and a senior staff editor on the Food desk. She teaches journalism at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, from which she graduated, and lives in North Carolina with her family. Mergers and Acquisitions is her first book.