Let’s be honest. Kids are kind of creepy.

If you have kids, I’m probably not talking about yours (probably). But of the kids out there who are trying to be frightening, many are doing a good job.

After all, how many novels, films, and TV episodes—looking for a quick scare—rely on some pale girl with long hair slinking through an old house, or some boy crouched in a dark room singing nursery rhymes in slow, minor keys? The commercial industry of fear knows if the product scares, you keep producing it. And, in the end, what’s creepier than waking at night to the sound of a child’s laughter—when you don’t have kids?

As an adolescent boy, I didn’t cope well with the trope. After seeing The Ring (creepy ghost girl), I found myself paralyzed, watching ShamWow infomercials into the early morning, terrified that if I turned the television off, the girl might crawl out of the screen at me. After reading Pet Sematary (creepy resurrected boy), I discovered that checking under my bed was a new, necessary step before sleep. And then, it was The Shining (creepy ghost twins, good Lord) that for months sent me sprinting down my parents’ dark hallway for the light switch.

Back then, if I were to imagine a face for bump in the night, it was always a creepy child’s. Never once did I have a clear idea of what these kids would do to me—what they even could do, small as kids are. But that never stopped me from growing frustrated, even angry, when reading a story and coming across yet another creepy child, knowing that yet again I’d find myself sleepless that night, worried some small set of unblinking eyes watched me through the ceiling vent.

I feel like I should say that I like kids. It’s not like I’ve avoided them in the various jobs I’ve worked. I’ve overseen afterschool programs and summer camps, and I’ve taught chess lessons in the long-term wings of children’s hospitals. There’s a unique joy in helping them, even a little, especially the ones whose support networks aren’t strong or consistent.

Isn’t it odd how we tend to fear things that appear in need?So it’s strange that, as an adult, I still find myself sensitive to the trope, and it seems even more strange when I consider those different renditions of ghostly kids in literature and film, with their pale and soot-streaked skin, untrimmed nails, and hair clinging to their foreheads as if in a fevered sweat. In all probability, under a bright light these horror children would look less demonic than sick, hungry, and neglected.

Isn’t it odd how we tend to fear things that appear in need?

It’s a pattern that shows true with most of our monsters, the standard Gothic ghouls that pervade our literature and film. Vampires, at least in their traditional, Nosferatu-like forms, appear infirm and starved, as if recuperating from a long illness. Zombies appear injured and limping, with shell-shocked expressions. Ghosts moan and wail from the bounds of their afterlife, as if we could set them free. And Frankenstein’s monster is stitched together, nails hammered into its neck, its heavy movements seeming painful. Sure, these creatures are startling when rattling chains and gnashing teeth. But their bodies alone, designed to frighten an audience, so often appear as if they’re the real victims.

All of this seems doubly true for “scary” children. Kids, who outside the frame of frightening fiction are obviously as vulnerable as it gets—and yet they creepify the worlds of The Exorcist, The Children of the Corn, and The Omen, and even fantasy stories like those first eerie moments of HBO’s Game of Thrones. The trope certainly isn’t limited to speculative fiction and otherworldly genres. Classic literary novels, like Shirley Jackson’s We Have Always Lived in the Castle and novellas like Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw, explore the disquieting feelings of fear and pity that they arise in us.

Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude tells of Rebecca, a girl who eats dirt and stares ominously at adults. I’d even wager that early forms can be seen in Charles Dickens’ fiction—whether or not he intended it. His doll-like children, the Little Nells and Tiny Tims, show odd maturity and prescience in what they say, with a purity that leans a bit inhuman. For some readers (i.e. this one), they’re less loveable than perhaps Dickens intended, more discomforting. Even as a fan of Dickens’ books, I’ve always tended to skim the pages with kids. (And I will never forgive him for A Christmas Carol: the shock of two starved children emerging—ghastly!—from under The Ghost of Christmas Present’s robes.)

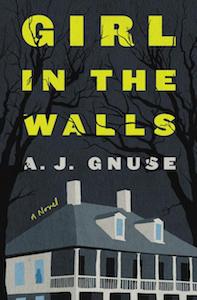

So, imagine my surprise, as I drafted my debut novel, to discover I was writing my own creepy child story. Though, as a twist on the concept, Girl in the Walls is no horror, and the orphan Elise, who haunts her old home, crawling within its walls, is no ghost or wicked entity. Elise hides in the attic and listens to the family beneath her. When they leave for the day, she emerges and gathers what she needs to survive. She sneaks cereal and food the family won’t notice missing. She enjoys reading mythological stories and whatever else she can find on their bookshelves. She’s a fan of The Black Eyed Peas. Elise is voyeuristic, invasive, and sure, a little creepy—but she’s also 11 years old. She’s hurting. She misses her parents. She doesn’t know where else to go.

As a young girl completely on her own, Elise is the one who is most vulnerable here. Yet to the family that’s unknowingly sharing a home with her, she seems, at times, an almost supernatural force, whose unknowingness feels like malevolence. To the two teenage sons, who sense their belongings have been moved, who hear sounds in the dead of night and wonder whether a shape moving at the end of a dark hallway is real—Elise is terrifying. And their fear eventually builds into anger.

Girl in the Walls asks the question: what does it mean to be the bump in the night? It’s a book about how strange our gut reactions may be, those impulses that steer on primal levels. It’s what happens when we strip away the narrative we expect—the threat of “monsters” and “evil” children—and consider what’s actually there. Why were we so scared?

Maybe it’s this:

In a scary movie, the child appears for the first time, pulling into frame, exposing its grim, sick face to the dim light. The audience—we’re startled. We’re overwhelmed because in that moment we try to process everything wrong at once. There’s hurt where we don’t want it, and an instinctual part of us panics. How can we help? Where do we even begin?

There are things we learn about ourselves from the stories that frighten us. Probably not all the lessons are uplifting ones, but I do think there is one here.

I think, sometimes, we’re frightened because we care.

__________________________________

Girl in the Walls is available from Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Copyright © 2021 by A.J. Gnuse.