8 Russian Poets Who Taught Me How to Write a Novel About Russia

Russians Don’t Recite Their Poetry, They Sing It

I came to Russian poetry late in life. I had already read the novels—Dostoyevsky and Tolstoy, Bulgakov and Turgenev—and the stories of Chekov, Gorky and Gogol Then, as a third year student in college, I spent an entire semester struggling to read Pushkin’s great verse novel, Eugene Onegin in Russian. When starting to read Russian poetry, you start with the greatest—Pushkin is Russia’s Shakespeare. It was Onegin that inspired me to attempt my new novel, The Revolution of Marina M. as a novel-in-verse. (I wrote 17 chapters before I came to my senses.)

A year later, on a student exchange to England, I took Soviet literature—in Russian, fully exploring the level of my linguistic incompetence. But it was in this class where I met the great poets of the Russian Silver Age—the time before and after the Revolution. The names still thrill me, like the names of old lovers. Akhmatova. Tsvetaeva, Mandelstam. Mayakovsky.

The professor was an elegant Soviet émigré named Valentina. While the other professors dressed in baggy cords and bulky scarves, she wore knee high suede boots and pearls. And she read aloud. Russians don’t recite their poetry, they sing it. The poets affected me differently than the fiction writers. Their voices weren’t disguised, in the way of the novelists’, they were direct—unique, variegated flavors of Russian genius, speaking directly to the hearer. Thought condensed to lightning.

The sounds and the sensibility of my new novel stems from these poets. This is the music of my Russian soul. Significant poets are missing here—Blok, Pasternak, Sophie Parnok. But I came to them much more recently.

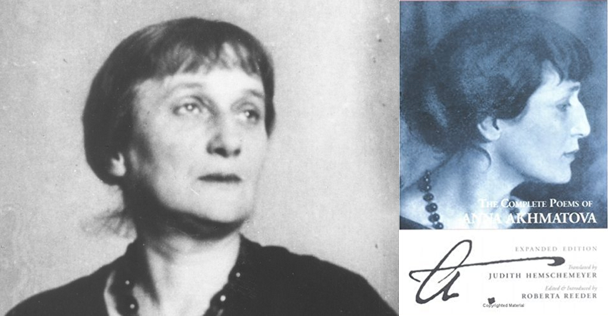

Anna Akhmatova

Anna Akhmatova

Russian poetry is a family affair. Its poets are born in constellations, like stars. And of the group born around 1880, the great Anna Akhmatova reigns supreme, the dark lady of Russian literature. I’ll always associate Akhmatova with Valentina and her pearls—the elegance, the gravity, the absolute authority. So much said with such little verbiage. Young Russian girls worshipped her, and still do. In the poem, “Muse,” a figure approaches a young Akhamatova out of the night. “You gave Dante the pages / Of the Inferno?” the poet asks. “And she answers, “Yes.”” Not many would risk that hubris.

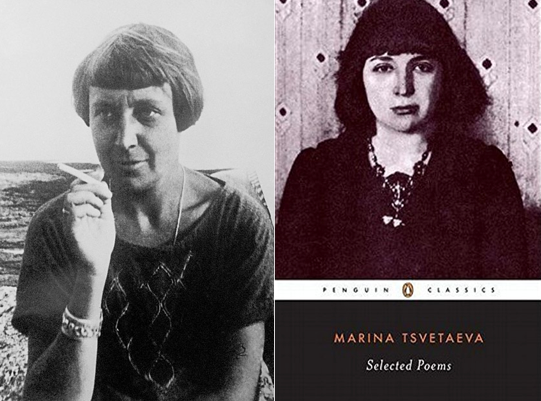

Marina Tsvetaeva

Marina Tsvetaeva

Although I admired the precise, elegaic Akhmatova, I felt immediate affinity with the passionate Marina Tsvetaeva. Fiery, biting, defiant, she was as sure of herself as Akhmatova was though as opposite by temperament as she could be. It’s not by accident I named my character Marina. A magician with language, personally turbulent, Tsvetaeva’s dashes and exclamation marks give speed and urgency to her work. Her “Ophelia: in Defense of the Queen” is a killer, in which she rags on Hamlet, “ . . . you defile the Queen’s / womb. Enough. A virgin cannot / judge passion . . .” That’s Tsvetaeva.

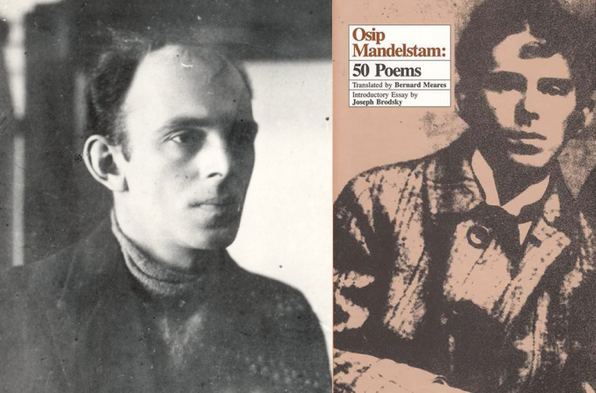

Osip Mandelstam

Osip Mandelstam

The most sophisticated on the page, Mandelstam was on the Akhmatova side of the spectrum, part of the Acmeist school—precision, and always the tie to world culture. Tsvetaeva had a hot affair with him—he of the long eyelashes, in her poem about him. His 1918 poem about the Revolution, “The Twilight of Freedom” gives you a sense of his bitter wit and stance as a poet as the apogee of cultural conscience, very Russian. “Brothers, let us celebrate liberty’s twilight, / The great and gloomy year...” when the very swallows have been pressed into battle legions. The end slays me. “…we’ll still recall in Lethe’s cold / That earth cost us a dozen heavens.”

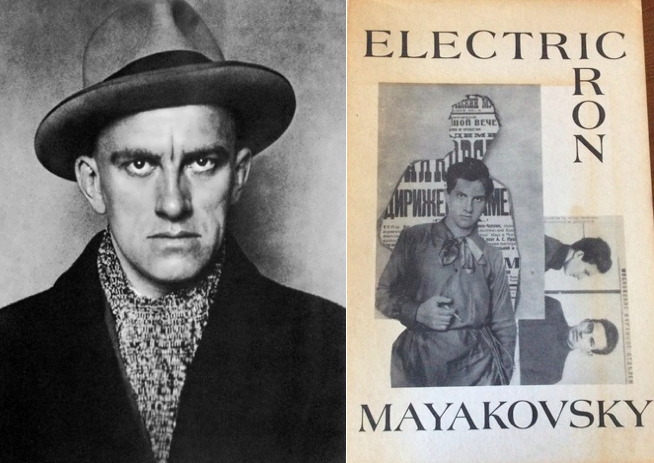

Vladimir Mayakovsky

Vladimir Mayakovsky

Mayakovsky, the great Futurist, was the one about whom they said, “He entered the Revolution as a man entering his own house.” A mass of contradictions—this great swaggering man, a giant, yet tender and even masochistic in his love life, desperately in love with a married woman and tormented with being the short end of a triangle. He was both the voice of the revolution—shouting, putting its feet on the table—but also “A Cloud in Trousers”:

You would not recognise me now:

a bulging bulk of sinews,

groaning,

and writhing,

What can such a clod desire?

Though a clod, many things!

Though politically at odds, he and Tsvetaeva had much in common and appreciated one another.

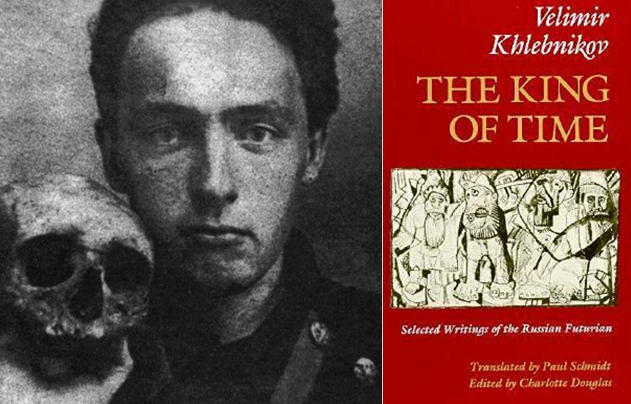

Velemir Khlebnikov

Velemir Khlebnikov

You’ve got to have the avant-garde to understand Russia. I think of Khlebnikov as Mayakovsky’s Mayakovsky. His sound poetry—“bo-bey-o-bi went the mouth”—fell under attack by the Soviet minders of culture. Mayakovsky defended his work, saying that there were “poets for the consumer and poets for the producer,” and a living literature needed both. Khlebnikov is the weird and imaginative advance guard of the Russian soul. I fell for his magnificent sprawling “Manifesto of the Presidents of the Terrestrial Globe”

Only we have fixed to our foreheads

The wild laurels of the Rulers of the Terrestrial Globe

We fire the moist clays of mankind

Into jugs and pitchers of time.

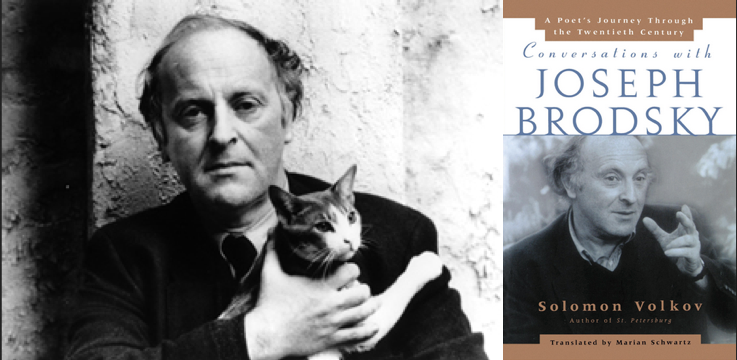

Joseph Brodsky

Joseph Brodsky

My dead-guy crush, my poetic Jim Morrison. Dry, witty, with a big undertow of sorrow, what a portrait of Russia. In the early 60s, he’d been imprisoned in a mental institution, and served a sentence for parasitism in in the Far North. A trial judge asked “Who has recognized you as a poet? Who has enrolled you in the ranks of poets?” “No one,” Brodsky replied, “Who enrolled me in the ranks of the human race?” He was Akhmatova’s heir and protégé. To hear him recite his own work is to hear the sound of the Silver Age, the coolness of Akhmatova, the bite and world-culture of Mandelstam. His poem, “May 24, 1986” on his 40th birthday, begins:

I have braved, for want of wild beasts, steel cages,

carved my term and nickname on bunks and rafters,

lived by the sea, flashed aces in an oasis,

dined with the devil-knows-whom, in tails, on truffles…

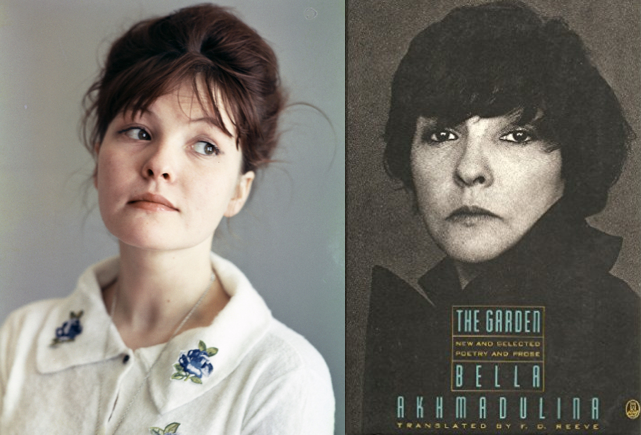

Bella Akhmadulina

Bella Akhmadulina

Akhmadulina is another member of the graduating class of the 1960s—along with Brodsky, Yevtushenko (to whom she was married) and Voznesensky. She was her generation’s glorious woman poet, dramatic, impassioned. I first read her long poem “Fairy Tale about the Rain” in Vogue magazine—it’s a metaphor for the way a vocation for art ruins you for “regular” life. The Russian poet is a dedicated creature, he or she doesn’t divide herself between the tea table or the bank desk and the page. In “Fairy Tale” the poet gets invited to a chic party, but the Rain follows her, ruining the carpet and watering the drinks. There’s a lot of Akhmadulina in Marina.

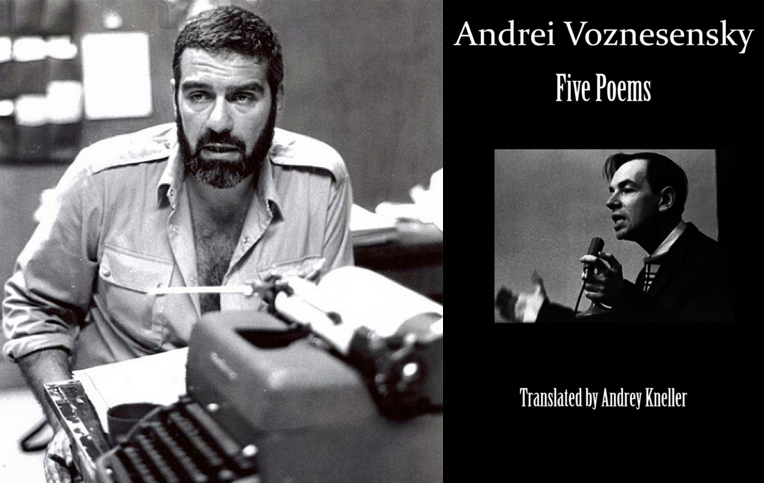

Sergei Voznesensky

The third of the great Class of 1960. I actually met Voznesensky in Portland, Oregon when I was a Russian student at Reed College—a black-leather-jacketed hipster, a world traveler. Like Yevtushenko and Akhmadulina, he walked a fine and ambiguous line between government approval and biting the had that fed him—a line one that Brodsky could not walk. Mayakovsky’s descendent, Voznesensky is pure Beat—right at home next to Ferlinghetti and Corso. I remember listening to East German punk rocker Nina Hagen to discover she’d lifted Voznesensky’s poem “Antiworlds” and set it to her own unique music. “AntiBukashkin the Academician, / Lapped in the arms of Lolobrigidas . . . ”