8 Books That Define and Defy the Canon of Hip Hop Literature

From Coast to Coast, Old School to New

About 20 years later than you would’ve expected, hip hop literature (and literature about hip hop) is finally developing something like a canon. You’d start with the likes of Nelson George and Greg Tate, shimmy through Jeff Chang’s Can’t Stop Won’t Stop and Dan Charnas’s The Big Payback, stop off with Tricia Rose and Bakari Kitwana, take in some of the best ghosted memoirs of the stars (probably Rza’s Tao of Wu and Jay-Z’s Decoded), before finishing up with more recent works like Hanif Abduraqqib’s brilliant Go Ahead In The Rain, or devoting yourself to inventory with the Ego Trip Book of Rap Lists.

But hip hop is a machine for undermining orthodoxy, so any canon is also automatically suspect, or ripe to be torn apart and reconfigured—and that’s what makes it such a vital force. This, then, is a list of books sitting at the edge of any putative “Best Of,” books that never quite belong, and whose lack of belonging is exactly what makes them work. Their relation to hip hop is much like my own—simultaneously “in” (I started and, for 15 years, ran the hip hop label Big Dada Recordings) and “out” (I’m a white, middle class guy from England). And perhaps that’s why I love them.

David Toop, The Rap Attack: African Jive to New York Hip Hop

(South End Press, 1984)

If you want to go back, way back, back to the old skool, then Rap Attack by the English writer and musician David Toop is the place to start. It was first published in 1984 and has the immediacy of history written on the hoof while that history is still happening. It’s fun and it conveys the author’s own exhilaration, which is never a bad place to start. There have been numerous revisions in later editions, but my feeling is the book should be read less for its accuracy of detail than for its evocation of a specific time and place. It’s a book which brilliantly captures the sense of creative explosion. Also: pictures.

Brian Cross, It’s Not About A Salary: Rap, Race and Resistance in Los Angeles

(Verso, 1993)

New York’s dominance of the hip hop world was, in actuality, fairly short-lived and the first scene to challenge that status was centered in Los Angeles. Brian Cross grew up in Ireland, but moved to LA in 1990 to study photography. He’s still probably better known as photographer B+, whose images made the magazine Rappages so special, and whose cover credits include DJ Shadow’s “Entroducing.” But the project he started while still at Cal Arts, It’s Not About A Salary: Rap, Race and Resistance in Los Angeles, is probably the first and certainly the most thorough overview of the early scene on the West (or Left) Coast. Starting off with an essay drawing on Mike Davis’s work on the privatization of public space, the book then expands into a series of Q&As with just about everyone on the scene, interspersed with Cross’s excellent black-and-white photographs. Although it’s very different from Rap Attack, they’re both books built on and exuding love, and this is probably what holds together every book listed here.

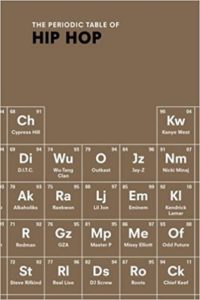

Neil Kulkarni, The Periodic Table of Hip Hop

(Ebury Press, 2015)

A British writer who deserves to be considerably better known in the US is Neil Kulkarni, who has long been one of the most insightful (and blunt) writers on hip hop from this side of the pond, from his days at Melody Maker onward. His The Periodic Table of Hip Hop might sound as if it will be a work of extreme objectivity, but Kulkarni has more opinions than most people have had breakfasts. This book will challenge, amuse and possibly offend you. The format of the series could have limited a lesser writer, but Kulkarni uses it as a leaping off point for a series of brilliant, provocative excursions. A guide book designed to get you lost.

Christine Otten (trans. Jonathan Reader), The Last Poets

(World Editions, 2018)

Anyone really hoping to come to grips with the roots of rap and how it stands in a continuum with other African-American musics could do a lot worse than grab a translation of The Last Poets, the remarkable novel by Dutch writer Christine Otten (trans. Jonathan Reader). Otten spent a number of years interviewing everyone she could who had a connection to the godfathers of rap and spoken word (only Jalal Nuriddin refused her requests). Originally planned as a work of non-fiction, she came to realize that the novel provided the only form through which she could fully make the story live. It works—in fact, it works magnificently. And she provides a kind of manifesto when she writes in the Irish Times, that its success (and, by extension, the success of all writing) relies on empathy: “Without empathy there is no good fiction, and also no real connection between people from whatever background. Real human contact means change, because what arises from it is not you or the other, but something new.”

Nik Cohn, Triksta: Life and Death and New Orleans Rap

(Knopf, 2005)

Perhaps the book on this list most clearly written from an outsider’s perspective (and also the most explicit about it) is Triksta by Nik Cohn. Brought up in Northern Ireland, Cohn made his name aged only 23, when he published his account of the first years of rock ‘n’ roll, Awopbopaloobop Alopbamboom, in 1969. He followed it up with the essay which formed the basis for the film Saturday Night Fever, plus a host of other books. Aged 55, he moved back to New Orleans (having stayed there after coming off tour with The Who 30 years earlier), became fascinated by the city’s “bounce” scene and ended up managing a young rapper, with less than sparkling results. The book, on the other hand, is fantastic—unsentimental but full of heart, a genuine love for the city and its inhabitants, as well as a succession of off-the-wall ideas, including his theory that left-handed people are rhythm people (I put forward this idea in every piece I write about hip hop and it always gets cut by right-handed editors).

Kodwo Eshun, More Brilliant Than the Sun: Adventures in Sonic Fiction

(Quartet Books, 1998)

Kodwo Eshun is described in his biography for More Brilliant Than The Sun: Adventures in Sonic Fiction, as “not a cultural critic or cultural commentator so much as a concept engineer” and that begins to give some idea of what a wild read his book is. Operating mainly now in the fine art world, Eshun’s 1998 work about afrofuturism is also a work of afrofuturism. It contains more than enough (brilliant) hip hop to keep all but the most tramlined ‘head’ happy, but places it in a kind of disrupted continuum—the full spectrum brilliance of Black Music. As such, if it could be said to be about any one thing, it’s a kind of theorization of rhythm: “The Breakbeat is a motion-capture device, a detachable Rhythmengine, a movable Rhythmotor that generates cultural velocity.” Woah.

William Upski Wimsatt, Bomb the Suburbs: Graffiti, Race, Freight-Hopping and the Search for Hip-Hop’s Moral Center

(Soft Skull Press, 1994)

Bomb The Suburbs was written and self-published in 1994 by William Upski Wimsatt, who described himself as “both an extreme insider and an extreme outsider to hip-hop,” on account of his middle class upbringing and private education mixed with his years as a a graffiti writer. What makes it stand out from almost anything else written about the culture—inside or out—is Wimsatt’s bracing honesty and lack of piety. He says exactly what he thinks and if it offends you or confuses you, well that’s your problem. The book is a mess, all badly reproduced images and terrible page layouts, as you’d expect. But his voice comes through so strongly it feels like he’s sitting in front of you, and the sense of trying to build something bigger than just a book is palpable.

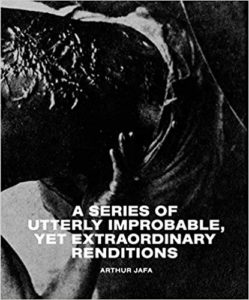

Arthur Jafa, A Series of Utterly Impossible Yet Extraordinary Renditions

(Cornerhouse Publications, 2018)

Finally, a kind of bonus. A book looking out beyond hip hop, but done in a way which is hip hop to its core. Arthur Jafa is a film director, cinematographer and visual artist who has worked with the likes of Spike Lee, Solange, Stanley Kubrick and Jay-Z. When some online browsing led me to the catalogue from his recent London show, A Series of Utterly Improbable Yet Extraordinary Renditions, I thought its high price tag was because it was a limited edition art book. Actually, its high price tag is because it’s huge. Almost 850 (large) pages long, it weighs in at just under 17.5 lbs, is packed with photographic images, specially commissioned essays from the likes of Fred Moten, Tina Campt and Ernest Hardy, amongst others, as well as texts from everyone from Amiri Baraka to Deleuze & Guattari (stopping off at Hilton Als, John Akomfrah, Cecil Taylor and Henry Dumas along the way). As such, it both harks back to the ringbinders of found images Jafa used to assemble as a child and to the collagist methodologies of hip hop itself. It’s such a rich, heady brew of theory, Theory, image and THEORY that I know I’ll be dipping into it for inspiration for years.

Will Ashon

Will Ashon is the author of Chamber Music: Wu-Tang and America in 36 Pieces, published by Faber & Faber in the US. He founded the record label Big Dada Recordings in 1996, which he ran for over 15 years, signing acts like Roots Manuva, Wiley, Diplo, Kate Tempest, MF Doom’s King Geedorah project and many more. He lives in London.