5 Writers Who Should be Feminist Saints

Julia Pierpont on Groundbreaking, Classic Authors

Virginia Woolf

Matron Saint of Writers

B. 1882, England

Feast Day: January 25

On a crisp October morning at “Oxbridge,” a woman crosses the grass. She has had an idea that excites her, and she is lost in thought. A man intercepts her: only scholars may walk along the turf; women are to stay on the gravel path. The woman complies, and the man moves on. It is a small moment, but the woman has lost her train of thought. She goes to the campus library, wanting to see a manuscript of Thackeray’s. But when she opens the library door, another man is there to meet her: women are not admitted unaccompanied. It is this series of refusals that would become the inspiration and opening to A Room of One’s Own, the feminist rallying text that explored two “unsolved problems”: women and fiction. Virginia Woolf, who owned and operated Hogarth Press with her husband, Leonard, recognized her unique privilege as a woman with artistic freedom. “I’m the only woman in England free to write what I like,” she observed. Woolf’s toughest battle was with her own mind, with the mental illness that eventually drove her to take her own life before the age of 60. “We cannot, I think, be sure what ‘caused’ Virginia Woolf’s mental illness,” wrote biographer Hermione Lee. “We can only look at what it did to her, and what she did with it. What is certain is her closeness, all her life, to a terrifying edge, and her creation of a language which faces it and makes something of it.” Her diaries reveal a mind unremittingly engaged. In an entry from 1927, while she was working on To the Lighthouse, Woolf wrote, “My brain is ferociously active. I want to have at my books as if I were conscious of the lapse of time; age and death.”

Maya Angelou

Matron Saint of Storytellers

B. 1928, United States

Feast Day: April 4

“In times of strife and extreme stress, I was likely to retreat to mutism. Mutism is so addictive. And I don’t think its powers ever go away.” A surprising admission for a woman who, by age 40, had lived in Egypt, in Ghana, and all around the United States; who’d worked as a professional dancer, a prostitute, an activist, a singer, a lecturer; and who would become a prolific writer.

Severe childhood trauma triggered Maya Angelou’s mutism at the age of eight: she’d been raped, and after her testimony in court, her rapist had been violently murdered. Her muteness lasted for nearly five years before lifting—but its dark appeal never left her. “It’s always there saying, ‘You can always come back to me. You have nothing to do—just stop talking.’” Angelou resisted the urge. At 41, she published her first and best-known book, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, which tells the story of that early trauma. In plays, in poems, in autobiographies and spoken-word albums and children’s books, she would tell stories for the rest of her life. “The writer has to take the most used, most familiar objects—nouns, pronouns, verbs, adverbs—ball them together and make them bounce, turn them a certain way and make people get into a romantic mood; and another way, into a bellicose mood,” she said at age 75. “I’m most happy to be a writer.”

Phillis Wheatley

Matron Saint of Readers

B. 1753, West Africa

Feast Day: May 8

The first black American to publish a volume of poems, and the second American woman to do so, was called Phillis Wheatley—a name given to her not by her parents but by her owners. The Wheatleys of Boston named her after the slave ship that carried her from West Africa. She was seven. The Wheatley family, known progressives, encouraged young Phillis’s education. “Without any Assistance from School Education, and by only what she was taught in the Family,” John Wheatley wrote, “she, in 16 Months Time from her Arrival, attained the English Language, to which she was an utter Stranger before, to such a Degree, as to read any, the most difficult Parts of the Sacred Writings, to the great Astonishment of all who heard her.” Many colonists doubted the authenticity of Phillis’s talents, and to silence skeptics, she endured an examination in court. When her collection, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, was published in 1773, she became the most famous African on the planet—according to Henry Louis Gates, Jr., “the Oprah Winfrey of her time.” Eventually gaining her freedom, she became a voice for the colonists as the American Revolution approached, writing such poems as “To His Excellency General Washington.” In 1776, Washington received her at his headquarters in Cambridge. Despite all her success and apparent patriotism, however, Wheatley recognized the complexity of her position, and her writing foreshadowed another great war, still nearly a century away. From her poem “On Being Brought from Africa to America”:

Some view our sable race with scornful eye,

“Their colour is a diabolic die.”

Remember, Christians, Negros, black as Cain,

May be refin’d and join th’ angelic train.

Mary Wollstonecraft and Mary Shelley

Matron Saints of Creation

B. 1759 and 1797, England

Feast Day: August 30

“If I cannot inspire love, I will cause fear; and chiefly towards you my arch-enemy, because my creator, do I swear inextinguishable hatred,” the creature tells his creator in Mary Shelley’s 1818 gothic classic Frankenstein. “You shall curse the hour of your birth.” Some literary critics have interpreted the novel as a “birth myth,” in which Shelley confronts “the drama of guilt, dread, and flight surrounding birth and its consequences.” The subject of childbirth was a fraught one for the author. At 18—a year before she would begin writing Frankenstein—she suffered the loss of a baby girl, born two months premature. Shelley’s own mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, died of childbed fever just 11 days after giving birth to her. Wollstonecraft was an author herself. Her “Thoughts on the Education of Daughters,” published in 1787, begins with the assertion that it is “the duty of every rational creature to attend to its offspring.” She argued the importance of women’s education in “A Vindication of the Rights of Women”: “Taught from their infancy that beauty is woman’s sceptre, the mind shapes itself to the body, and, roaming round its gilt cage, only seeks to adorn its prison.” (She couldn’t know the parallel she was making with the creature her daughter would imagine decades later. Much like Frankenstein’s monster, women are confined by their own physical form.) Though Wollstonecraft would not live to see the woman her daughter became, she did all she could in her lifetime to ensure that her daughter, and all daughters, would grow up with greater opportunity than the women who came before them.

Jane Austen

Matron Saint of Irony

B. 1775, England

Feast Day: December 16

I do not want people to be very agreeable, as it saves me the trouble of liking them a great deal.

–Jane Austen

Jane Austen knew how to be wicked. So much so that very few of her letters survive, her family having taken great pains, after her death, to destroy or censor any comments they deemed too forthright. Surprising, then, how in recent years, professing a love for Austen has become akin to professing oneself a romantic. The last decade or two have seen an uptick not just in direct adaptations of Austen’s works but in novels and films depicting “Janeites”—avid Austen fans who dream of forgoing their modern lives for entry into the ideal worlds of her fiction. The misreading was something Austen encountered even in her own day. In 1816, she wrote “Plan of a Novel, According to Hints from Various Quarters,” a brief parody of the “ideal novel,” written in response to suggestions she’d received from readers of her work. In it, the Heroine—“a faultless character herself, perfectly good, with much tenderness and sentiment, and not the least Wit”—meets with the Hero, who is “only prevented from paying his addresses to her by some excess of refinement.” Later the Heroine’s ailing father, a clergyman, “after 4 or 5 hours of tender advice and parental Admonition to his miserable Child, expires in a fine burst of Literary Enthusiasm.” In a surviving letter to her niece, she wrote, “Pictures of perfection, as you know, make me sick.”

__________________________________

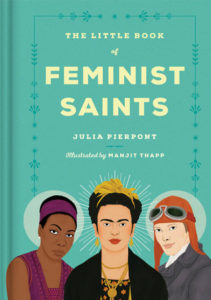

From The Little Book of Feminist Saints. Used with permission of the publisher, Random House. Copyright © 2018 by Julia Pierpont. Illustration copyright © 2018 by Manjit Thapp.