5 Poems to Appease the Infamous Welsh Christmas Horse Skeleton

Here's What to Do if Mari Lwyd Shows Up at Your Door

The holiday season is upon us, bringing with it mistletoe, chestnuts roasting on an open fire, and skeletal horses demanding entrance to our homes. Yes, it is nearly time for the annual appearance of Mari Lwyd: a horse skull with beer bottle eyes, shrouded in white linen and strung with ribbons and bells. Rigged with a mouth that could open and close like a puppet’s, Mari would recite verse to unsuspecting neighbors, who had to answer in turn or else ply the wassailers with beer, cake, and “a good deal of romping.”

Mari Lwyd in Llangynwyd, Glamorgan, est. 1904-1910

Mari Lwyd in Llangynwyd, Glamorgan, est. 1904-1910

Though believed to be of pre-Christian origin, the Mari Lwyd tradition was first recorded in the early 19th century, and its evolution remains somewhat mysterious. Writing in 1888 in the journal Archaeologia Cambrensis, David Jones observed that “the word ‘Lwyd’ means ‘Blessed.’ How the name ‘Blessed Mary’ has come to be applied to the skeleton of a horse’s head, decked with ribbons and other finery, as will be presently described, is a question easier put than answered.” Today, the tradition has more or less diminished, save for a few exceptions; you can see Mari at St. Fagan’s National History Museum every December, and each January the town of Chepstow plays host to visiting Maris from across Wales for an annual celebration.

Should these equine zombies ever rise en masse again, the only way to defeat the horrible specters is to arm yourself with verse. Here are some poems you might recite to the wassailing skull if it arrives at your door.

Mari Lwyd as Lana Del Rey

Mari Lwyd as Lana Del Rey

If you want to be quite literal . . .

Donald Hall’s “Names of Horses,” originally published in 1977, eulogizes a series of beloved farm horses who, when they are “old and lame” with “shoulders [that] hurt bending to graze,” are shot and laid to rest by their owners. The poem concludes with an image Mari Lwyd is sure to recognize:

For a hundred and fifty years, in the Pasture of dead horses,

roots of pine trees pushed through the pale curves of your ribs,

yellow blossoms flourished above you in autumn, and in winter

frost heaved your bones in the ground – old toilers, soil makers . . .

If you want to choose a Welsh poet . . .

Sometimes referred to as “Swansea’s most famous son,” you can’t go wrong with Dylan Thomas. Though technically a work of prose, “A Child’s Christmas in Wales” would bring a tear to any anthropomorphic horse skeleton’s eye. Here’s a good bit:

Years and years ago, when I was a boy, when there were wolves in Wales, and birds the color of red-flannel petticoats whisked past the harp-shaped hills, when we sang and wallowed all night and day in caves that smelt like Sunday afternoons in damp front farmhouse parlors, and we chased, with the jawbones of deacons, the English and the bears, before the motor car, before the wheel, before the duchess-faced horse, when we rode the daft and happy hills bareback, it snowed and it snowed. But here a small boy says: “It snowed last year, too. I made a snowman and my brother knocked it down and I knocked my brother down and then we had tea.”

“But that was not the same snow,” I say. “Our snow was not only shaken from white wash buckets down the sky, it came shawling out of the ground and swam and drifted out of the arms and hands and bodies of the trees; snow grew overnight on the roofs of the houses like a pure and grandfather moss, minutely -ivied the walls and settled on the postman, opening the gate, like a dumb, numb thunder-storm of white, torn Christmas cards.”

If you want to go traditional . . .

In Mari Lwyd’s heyday, the verses traded between wassailers and the households they visited were rhyming insults, delivered, of course, in Welsh. One common opening went thusly:

Wel dyma ni’n dwad (Well here we come)

Gy-feillion di-niwad (Innocent friends)

I ofyn am gennad (To ask leave)

I ofyn am gennad (To ask leave)

I ofyn am gennad i ganu (To ask leave to sing)

Or just take a cue from these lads:

If you want to banish the horse skeleton . . .

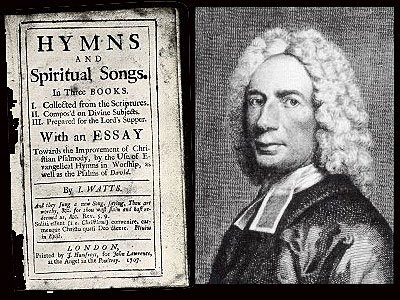

For those who feel as the Reverend William Roberts did when he wrote this of Mari Lwyd in The Religion of the Dark Ages (1852) —”I wish of this folly, and of all similar follies, that they find no place anywhere apart from the museum of the historian and the antiquary”—the words of another clergyman may be of use. To chasten Mari and her drunken minders, try “Against Evil Company” by 18th-century minister and hymn-writer Isaac Watts:

Why should I join with those in Play,

In whom I’ve no delight,

Who curse and swear, but never pray,

Who call ill Names, and fight.

I hate to hear a wanton Song,

Their Words offend my Ears:

I should not dare defile my Tongue

With Language such as theirs . . .

If you want the horse to come inside . . .

At the end of the day, the point isn’t really to send Mari Lwyd packing. Her visit is meant to bring luck to your household during the year ahead, and besides, she’s an undead horse who’s been rhyming since the pre-Christian era—realistically, you won’t outsmart her. When you’re ready to concede, William Butler Yeats’s “A Drinking Song” will do, whether you’re sighing in romantic admiration or resigned defeat.

Wine comes in at the mouth

And love comes in at the eye;

That’s all we shall know for truth

Before we grow old and die.

I lift the glass to my mouth,

I look at you, and I sigh.

Nadolig llawen a blwyddyn newydd dda!

Blair Beusman and Jess Bergman

Blair Beusman and Jess Bergman are Literary Hub's Associate Editor and Features Editor, respectively.