5 Books You May Have Missed in April

From the Dissolution of the Soviet Union to Unchecked Internet Fame

Some months’ searches are richer than others. I wish this list allowed me to cover 15 to 20 books, because I want to make sure you hear about Breasts and Eggs by Mieko Kawakami, about the repression of all things female in modern Japan—and maybe you have or will, because a big newspaper just covered it. But I’d also want to share Little Siberia by Antti Tuomainen, whose Finland-set thrillers are as funny as they are well paced; Gee Svasti’s Last to the Front, about Siamese soldiers fighting in France during World War I. . . See how I am? Let me confine myself to the five books I’ve chosen that I’m allowed, and maybe one of them will make it to your TBR pile.

Yair Assulin, The Drive

(New Vessel Press, trans. Jessica Cohen)

The Drive follows an Israeli soldier, in a car with his father, en route to see a military psychiatrist who may or may not be able to help the young soldier in his dilemma. He wants to leave the army, but he doesn’t want to leave the army, for reasons that make complete sense to him—but not to the bureaucracy. The most remarkable part of this book may be in its exploration of how impossible the mentally healthy find it to participate in the journey of the mentally ill. The soldier’s parents love him deeply but cannot find a way in to their son’s pain; both sides feel betrayed and isolated. A superb debut from one of Israel’s younger prize-winning authors translated by Cohen, who shared the Man Booker International Prize with David Grossman for her translation of A Horse Walks into a Bar.

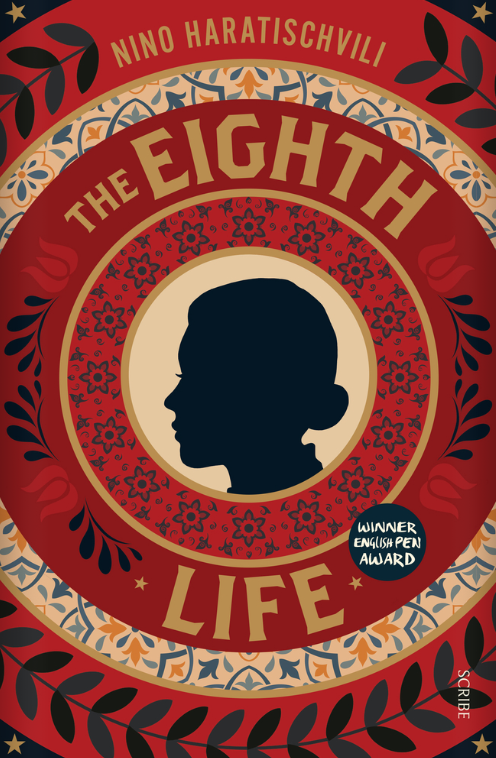

Nino Haratischvili, The Eighth Life (for Brilka)

(Scribe US, trans. Charlotte Collins and Ruth Martin)

I guarantee you have not seen a story before about the chocolate-making industry in Georgia—the Eastern European Georgia, that is. The Eighth Life (for Brilka) clocks in at 944 pages, a solid brick of a book with a gorgeous red-and-gold cover reminiscent of Georgian folk art. A worldwide bestseller already nominated for the Man Booker International Prize, Haratischvili’s epic family saga about how the Russian Empire dissolved and became the Soviet Union and dissolved and became separate states (Georgia in revolution, then) makes clear that Georgia is not and never has been “part” of Russia. It’s a country with its own language and alphabet and landscape and culture and ethos. The eight “books” that make up the novel may begin with a man, the master chocolatier whose secret recipe brings wealth to the family, but they each center on a woman in that family, and these stories bring to life the blank spaces the various political dynasties wanted kept secret from their people.

Kathe Koja, Velocities: Stories

(Meerkat Press)

This collection should be your next read if you’re (like me) a huge Samanta Schweblin fan. Like Schweblin (Fever Dream, Mouthful of Birds), and really, before Schweblin, Koja tells it slant and backwards, in dark narratives that are so immersive they read like truth. Fantasy, horror, sci-fi—it’s tough to fit them into genres, and that’s perfectly all right. Some short story collections unite by tone. This one unites through daring, through allowing characters to reach their limits, whether those are murder, breastfeeding, necrophilia, and seeing humanity at those limits. Even if that humanity is creepy, it’s undeniable. Because she plays with tone, genre, structure, and more, Koja never loses a reader’s interest. Watch out.

Ellen Meeropol, Her Sister’s Tattoo

(Red Hen Press)

Her Sister’s Tattoo shows women being political. Gasp! Meeropol tells the story of Rose and Esther, sisters whose political convictions separate them even as their familial love remains strong. It’s 1968, and the siblings attend a protest that turns violent. In the process, they are arrested. One does the time, one takes a plea bargain. It’s a long book, discursive even, perhaps because Meeropol wants readers to understand a great deal about these characters without turning them into cardboard cutouts. She succeeds. One of the great pleasures in reading Her Sister’s Tattoo lies in its attention to the five senses, from patchouli in the air at the opening protest to a child drawing on newsprint with “four fat crayons” to the sight of origami cranes. An exploration about how we make decisions on where our loyalties lie.

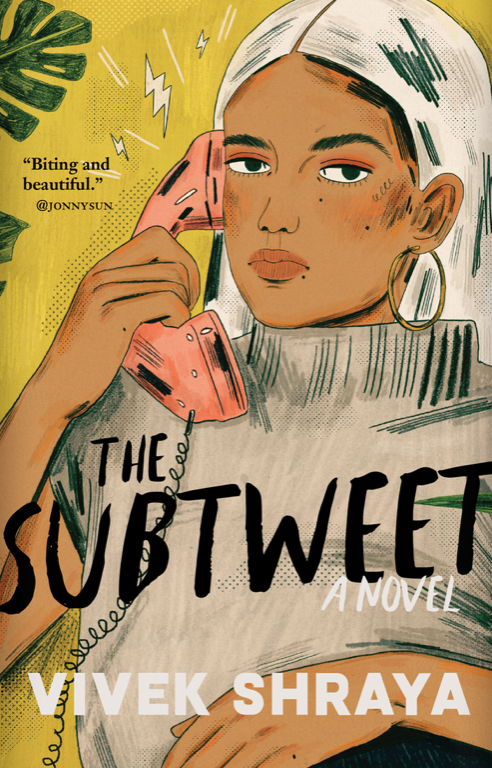

Vivek Shraya, The Subtweet

(ECW Press)

This novel should help Shraya, already a force for good in several artistic communities, find a much larger audience for her prose. Neela Devaki has a song covered by an internet-famous artist named Rukmini. Before you can say “hey girl,” the two have fallen deeply in friendship. Before you can say “bitch please,” one of them stagnates and the other soars. Shraya’s narrative moves fast, so fast you’ll want to slow down and read paragraphs again because they contain biting commentary on things like “a volunteer modelling last season’s lilac-grey hair” and an audience applauding, “festival lanyards flapping.” However, her exploration of how quickly relationships can live and die in our always-on world rests beneath the pitch-perfect wit.

Bethanne Patrick

Bethanne Patrick is a literary journalist and Literary Hub contributing editor.