5 Books Making News this Week: Religion, Refugees, and Odysseys

Alice McDermott, Jenny Erpenbeck, Daniel Mendelsohn, and More

CLMP, the Community of Literary Magazines and Presses, launches its 50th anniversary this fall, with a salute to founders George Plimpton, Russell Banks (not yet a famous novelist back then, but rather the publisher of Lillabulero magazine), Clayton Eshelman, Jules Chametzy and others. Rumor has it that Jackie O even MC’d one of their awards ceremonies way back when. They will kick off their 50th year at “Pierogies from Heaven” on November 8th, where they’ll celebrate Rob Spillman as a literary energizer extraordinaire and Wave Books for paradigm indie publishing.

The $50K Kirkus Prize finalists include Lesley Nneka Arimah’s What It Means When a Man Falls from the Sky: Stories and Jesmyn Ward’s Sing, Unburied, Sing. Rachel Cusk’s Transit, Josip Novakovich’s Tumbleweed, and Michelle Winters’ I Am a Truck make Canada’s $100K Scotiabank Giller Prize longlist. The judges note trends: “the plight of the marginalized, the ongoing influence of history on the present, the way it feels to grow up in our country, the way the world looks to the psychologically damaged. But 2017 was also a year of outliers, of books that were eccentric, challenging or thrillingly strange, books that took us to amusing or disturbing places. In fact, you could say that the exceptional was one of 2017’s trends. It gave the impression of a world in transition: searching inward as much as outward, wary but engaged.”

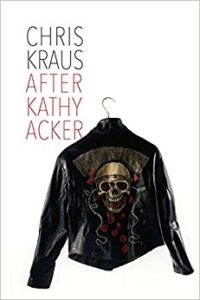

Alice McDermott’s eighth novel is “superb,” “masterful,” “a tour de force,” “a triumph;” Daniel Mendelsohn’s An Odyssey focuses on fathers and sons, Carmen Maria Machado’s first book is a collection of “bizarre, magical” stories, Jenny Erpenbeck humanizes the refugee crisis in Germany, and Chris Kraus memorializes punk-rock feminist writer Kathy Acker.

Alice McDermott, The Ninth Hour

Already named a finalist for the Kirkus Prize in fiction, McDermott’s eighth novel begins with a suicide in early 20th-century Brooklyn, and fans out to follow his widow, the child she bears, and nuns from the Little Nursing Sisters of the Sick Poor who come to her aid, the child Sally as an adult, and even her future children.

Rebecca Steinetz (Boston Globe) reviews the book in glowing terms:

In the tour de force opening chapter of The Ninth Hour, Alice McDermott’s splendid new novel, Irish immigrant and professional failure Jim sends his young wife out shopping and gases himself in his fourth floor apartment. The first sentence sets the scene: a “dark and dank day” with “cold spitting rain” and “a low, steel-gray sky.” In the third paragraph the overcoat Jim rolls lengthwise and lays across the threshold announces his intent. The back story emerges as he completes his preparations: the loss of his job as a trainman because “he liked to refuse time” by rebelliously refusing to get up in the morning. It is a loss all the more devastating when he learns from his justifiably angry wife that there is a baby on the way.

Lily King (Washington Post) calls The Ninth Hour “superb and masterful,” and adds, “the book’s real thrills are the feats of its storytelling.”

Katherine A. Powers (Barnes and Noble Review) concludes, “The novel’s title itself points to sacrifice, the ‘ninth hour’ being one of the canonical hours, 3 pm (notionally the ninth hour after dawn), the hour that Christ died on the Cross, sacrificing himself for the sins of the world. Such fascination with sacrifice and its endless demands— willingly embraced, reluctantly endured, or guiltily refused—belongs to the Catholic Church of an earlier age and to a vanished sensibility and milieu, all evoked to perfection by McDermott. This is an exquisitely deep novel and a triumph.”

Daniel Mendelsohn, An Odyssey

Award-winning memoirist, critic, classics professor Mendelsohn uses his method of blending ancient texts and personal narrative to write his most personal story yet, about his father, and The Odyssey.

“For a book about a man who missed a lot of his son’s life, The Odyssey has much to say about fathers and sons,” notes John Freeman (Boston Globe). “Homer’s epic begins and ends with a son in search of his father, after all, and Odysseus’s infamous island tests aside—besides the sirens!—the book’s innermost ring concerns how fathering is for many men the ultimate measure of time.”

Dwight Garner (New York Times) admires An Odyssey:

There’s an early scene in Mendelsohn’s new book . . . in which Daniel, a natty gay man, looks on in horror as Jay buttons himself into a shiny brown shirt.

“I said, Daddy, we’re on a Mediterranean cruise, you can’t wear brown polyester, and I took the shirt and walked to the balcony and threw it into the sea. Whaaat!?! he cried, that was an expensive shirt! He strode across the stateroom to the balcony and looked forlornly down as the shirt, which on contact with the water had taken on a dense animal gleam, like the skin of a seal, briefly bobbed along until it finally sank under its own weight.”

These sentences—well made, revealing and funny—are typical of Mendelsohn’s book. What catches you off guard about this memoir is how moving it is. It has many complicated things to say not only about Homer’s epic poem but about fathers and sons.

Jonathan Russell Clark (San Francisco Chronicle) sounds a cautionary note: “The trouble with Mendelsohn’s multifaceted style is that deep scrutiny, personal narrative, literary history and classics-derived life lessons don’t all possess wide appeal. Readers may find they have more interest in one of the five braided techniques (most likely the narrative with Mendelsohn and Jay), which will mean they’ll have to plod through the other parts in order to get to the stuff they like. But for those with broad curiosity and a tolerance for intellectual hopscotching, An Odyssey is a journey worth taking.”

Carmen Maria Machado, Her Body and Other Parties

This first story collection by the Artist in Residence at the University of Pennsylvania who has published in The New Yorker, Granta, and Electric Literature, among others, has already gained traction as a National Book Award and Kirkus Prize fiction finalist.

Suzette Smith (The Portland Mercury) notes, “Carmen Maria Machado’s followed an unusual trajectory to reach me: I casually opened her collection Her Body and Other Parties, and it lit me on fire. I’ve experienced this with only a handful of writers—Diane Cook and Leanne Shapton among them—whose creativity and language are fearless and whose images are so specific and unusual that they carry heavier metaphorical resonance than something more homogenized.”

A starred Kirkus review notes, “Machado’s debut collection brings together eight stories that showcase her fluency in the bizarre, magical, and sharply frightening depths of the imagination.”

Tara Block (PopSugar) calls it one of her favorites of the year (so far): “Carmen Maria Machado blends emotion, beauty, and creepy storytelling in Her Body and Other Parties. She plays with ‘psychological realism and science fiction, comedy and horror’ and bends genre to create stories that ‘map the realities of women’s lives and the violence visited upon their bodies.’”

Jenny Erpenbeck, Go, Went, Gone

German author Erpenbeck won Italy’s Premio Strega Europeo for this novel, translated from the German by Susan Bernofsky, and featuring a complex and revealing look at African asylum seekers in Berlin.

James Wood (The New Yorker) writes:

Jenny Erpenbeck’s magnificent novel . . . is about “the central moral question of our time,” and among its many virtues is that it is not only alive to the suffering of people who are very different from us but alive to the false consolations of telling “moving” stories about people who are very different from us. Erpenbeck writes about Richard, a retired German academic, whose privileged, orderly life is transformed by his growing involvement in the lives of a number of African refugees—utterly powerless, unaccommodated men, who have ended up, via the most arduous routes, in wealthy Germany. The risks inherent in making fiction out of the encounter between privileged Europeans and powerless dark-skinned non-Europeans are immense: earnestness without rigor, the mere confirmation of the right kind of political “concern,” sentimental didacticism. A journey of transformation, in which the white European is spiritually renewed, almost at the expense of his darkly exotic subjects, is familiar enough from German Romanticism; you can imagine a contemporary version, in which the novelist traffics in the most supple kind of self-protective self-criticism. Go, Went, Gone is not that kind of book.

Eileen Battersby (The Guardian) writes, “Great fiction doesn’t have to be real, but it does have to be true. Erpenbeck’s powerful tale, delivered in a wonderfully plain, candid tone, is both real and true. It will alert readers, make us more aware and, it is to be hoped, more human.”

“It is not Erpenbeck’s diffident protagonist that makes the lasting impression,” points out Robert Lemon (World Literature Today). “Instead, the reader is left with the cold fury of her polemic against Germany and the European Union’s bureaucratic response to this humanitarian crisis, their willingness to allow people who have “survived the passage across a real-life sea” to “drown in rivers and oceans of paper.” In the United States where the Supreme Court has partially upheld the Trump administration’s travel ban and border patrols raid aid shelters for migrants, readers may be surprised by this excoriation of Germany’s relatively generous immigration policies. Yet Go, Went, Gone reminds us that it is the mission of art to engage our imaginative empathy and hold the status quo to a higher account.”

Chris Kraus, After Kathy Acker

The post-punk feminist performance artist and writer is memorialized by a woman who was close to Acker, but not necessarily in a good way. “Even though I didn’t know her, Kathy had been an important figure to me—at first, through her writings, and later on, through our uncomfortably similar relationships with Sylvère,” Kraus tells the Los Angeles Review of Books’s Mathias Viegener, Acker’s literary executor. “At the height of her fame, I observed how people related to her, or her power and fame, and felt very ambivalent. Her glamourous persona was the opposite of my poetry-grunge aesthetic, but I felt weirdly protective of her—as if people didn’t understand at what cost her persona was cultivated. Clearly, I wildly and inappropriately identified with her.”

“The book begins at Acker’s funeral, a surreal and stylish scene populated by critical theorists, underground artists, and crystal healers,” writes Anna Ioanes (Los Angeles Review of Books). “Beginning at the end might seem like a cheap postmodern trick, but instead, this structure orients readers with an endpoint and asks the question: how did we get here? By opening in a moment immediately ‘after’ Kathy Acker, in the midst of her mourners, Kraus begins to map out the extensive and shifting network of Acker’s mentors, friends, lovers, and rivals.”

Josephine Livingstone (New Republic) concludes:

Over the course of After Kathy Acker, Kraus has been inside her diaries, burrowed inside her friendships, psychoanalyzed and praised a little and recorded much. But only with Acker’s death does the detail of Kraus’s research match the purpose for which it is intended: remembering with honor the dead writer.

Biography-writing is a very tricky form, and no reader could fault the dedication with which Kraus has chased down the archival and human remains of Kathy Acker on earth. As an Acker fan, I inhaled this book. But as the last pages turned, the biography’s lingering flavor was one of bitterness. Whether that was done in the name of the truth or in the name of dislike, we can’t know.

“After reading this book, would I have wanted to know Kathy Acker?” asks Des Barry (3:AM Magazine). “Maybe. Maybe not. I’ve always thought that writing and where it takes the reader is more important than the personality, although in Kathy Acker’s case, her persona was as much a work of confrontational art as her novels. Acker’s writing connects with a raw part of the psyche. After Kathy Acker is a definitive, exhaustive and brilliantly written biography of a writer who lived a chaotic, victorious, tragic, destructive and painfully romantic life; a writer who flared brightly in the literary world of the late twentieth century, and burned up like a meteor in the raw atmosphere of her own life’s creation. Chris Kraus’s biography resurrects that messy, post-punk, goddess-vision, and gives a tantalizing view of how to approach Kathy Acker’s inimitable writing.”

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.