5 Books Making News This Week: Refugees and Religious Conversions

Mohsin Hamad, Ayelet Gundar-Goshen, Emmanuel Carrère, and More

The 2016 Barnes and Noble Discover Awards for the best books published last year go to Abby Geni’s The Lightkeepers (fiction) and Matthew Desmond’s Evicted (nonfiction). Mohsin Hamid casts a refugee as the hero in his fourth novel, Hideo Yokoyama’s first crime novel translated into English is a “Jamesian police procedural,” Israeli novelist Ayelet Gundar-Goshen’s Waking Lions earns a literary award, Emmanuel Carrère’s “brilliant, shocking” book is now available in English, and Lauren Elkin follows in the footsteps of Jean Rhys, Virginia Woolf and George Sand.

Mohsin Hamid, Exit West

The Booker-award winning Pakistani-born author’s fourth novel is a love story set against a global refugee crisis. “I thought it was important to imagine a narrative where a migrant was the hero, the protagonist, and enjoyed all of the narrative sympathies that come with that role,” he tells Mother Jones’ Alexander Sammon. His narrative strategy works.

Michael Schaub (NPR) calls Exit West “at once a love story, a fable, and a chilling reflection on what it means to be displaced, unable to return home and unwelcome anywhere else.”

Stephen Lee (Newsday) writes, “The heroes at the center of Mohsin Hamid’s slim yet poignant new novel . . . start off in a hellish reality—an unnamed city, presumably somewhere in South Asia, where helicopters and drones darken the sky—but the magical portals they discover don’t offer a true escape from that reality but rather lead to new destinations with their own set of dangers. It’s a brilliant, fantastical framework that, in Hamid’s hands, highlights the stark reality of the refugee experience and the universal struggle of dislocation.”

“By mixing the real and the surreal, and using old fairy-tale magic, Hamid has created a fictional universe that captures the global perils percolating beneath today’s headlines, while at the same time painting an unnervingly dystopian portrait of what might lie down the road,” notes Michiko Kakutani (New York Times). “The world in Exit West is, in many respects, an extrapolation of the world we live in now, with wars like the one in Syria turning cities into war zones; with political crises, warp-speed technological changes, and growing tensions between nativists and migrants threatening to upend millions of lives.”

Hamilton Cain (Minneapolis Star-Tribune) concludes:

In a light yet vibrant coda, he flashes forward 50 years to Nadia and Saeed’s reunion in a cafe in their home city, now revitalized: “Above them bright satellites transited in the darkening sky and the last hawks were returning to the rests of their nests and around them passersby did not pause to look at this old woman in her black robe or this old man with his stubble.”

There are many indelible moments like this one throughout Exit West. Let the word go forth: Hamid has written his most lyrical and piercing novel yet, destined to be one of this year’s landmark achievements.

Hideo Yokoyama, Six Four, tr. Jonathan Lloyd-Davies

Yokoyama’s million-selling crime novel is the first of his books translated into English. “Yokoyama’s work is unique even here in Japan, with an emphasis on internal politics, and the central characters generally working outside of Criminal Investigations,” translator Jonathan Lloyd-Davies tells Culture Trip’s Michael Barron. “The political motivation of many of his characters, the tribal sense of loyalty, is particularly Japanese.”

Terrence Rafferty (New York Times Book Review) offers a surprising comparison:

What Yokoyama does in Six Four evokes—improbably—the fastidious ethical parsings of a novel by Henry James, all qualms and calibrations, and while that might not sound like a good idea, he makes it work. He writes, fortunately, in plain, declarative prose (ably translated by Jonathan Lloyd-Davies), and because Mikami is such an ordinary man the mental gymnastics he puts himself through are moving and sometimes deeply funny. A Jamesian police procedural—The Wings of the Perp, maybe? Not exactly. But this novel is a real, out-of-the-blue original. I’ve never read anything like it.

“This is a story about frustration at work—wanting to do what’s right vs. needing to do what’s expected,” writes Sarah Begley (Time). “Though it deploys common tropes of crime fiction and its lightly noir style, Six Four‘s unusual focus on the PR side of police work sets it apart and gives it unexpected heat. Yokoyama avoids simplistic moralizing, and instead offers the reader a compelling interrogation of duty.”

Ayelet Gundar-Goshen, Waking Lions, tr. Sondra Silverston

Israeli novelist Gundar-Goshen’s Waking Lions is joint winner (with Philippe Sands’s East West Street) of the J.Q. Wingate literary prize, which recognizes authors and writing that explore the idea of Jewishness to the general reader. “In Gundar-Goshen’s novel we enter a world where barbarism exists side by side with civilization,” notes the chair of judges, Bryan Cheyette. He calls the book “an incredibly compelling and enjoyable read which tackles an unsettling issue which engages with the ethical core of present-day Israel.”

Maureen Corrigan (NPR) calls Waking Lions “It’s a smart and disturbing exploration of the high price of walking away, whether it be from a car accident or from one’s own politically unstable homeland.”

Waking Lions “exposes a rot at the core of Israeli society,” concludes Adam Kirsch (Tablet).

That society, Gundar-Goshen suggests, is best reflected in Davidson, the owner of the restaurant where Sirkit works. Davidson turns out to be a far worse exploiter than he appears at first, yet Gundar-Goshen writes that he never consciously decided to hurt anyone: “The urge to do evil did not arise in him, and so he could neither overcome it nor abandon himself to it. He lived his life totally asleep. In a state of slumber that became a way of life. When he could take something, he took it. When he couldn’t, he tried to take it anyway. Not out of greed but out of habit.” It is the classic “banality of evil” argument, turned around to indict Israeli society—and our own.

Emmanuel Carrère, The Kingdom, tr. John Lambert

The French filmmaker, novelist and intellectual mixes fiction and memoir in his new book, a best seller in France. The English publication gathers accolades, beginning with a starred Kirkus review: “A passionate, digressive, empathetic history of religious rebels and the mystery of faith.”

John Cornwell (Financial Times) writes, “In The Kingdom, [Carrère] tells of his highly charged religious conversion to Christianity in parallel with a gripping history of the Jesus story. But what is fact about Jesus, and Carrère? What is fantasy? While the conversion narrative only occupies around a fifth of The Kingdom, it looms large as a nakedly frank account of a personal crisis. For the remainder, reflections on the origins of Christianity deconstruct and refract into versions of Jesus and the writer himself. The telling of these two Greatest Stories Ever Told, Jesus’s and his own, is only just redeemed from supreme narcissism by Carrère’s winning sense of irony.”

Tim Whitmarsh (The Guardian) calls The Kingdom “a brilliant, shocking book” and “a work of great literature,” and notes, “Carrère is not an easy writer to categorize, working as he does at the intersection between fiction, biography, autobiography and history. He is also—importantly—a screenwriter, and a sensualist who likes to feel the world he describes.”

Wyatt Mason (New York Times Magazine) argues that Emmanuel Carrère reinvented nonfiction. “Suddenly at the end of an exploration of a kind of darkness, the darkness of a lived life and its struggles, a moment of revelation occurs in which those struggles are revealed to be not at all what we supposed they were,” he concludes. “This sort of revelation—small but in a life, huge—is one of the very special things about Carrère’s work: how his books, at their ends, document what, hitherto in literature as in life, remains hidden. This consistent shift to small, hard revelation at the end of his books, is the most difficult thing to characterize, because the effect of these endings is produced through the accumulation of what precedes them, the tens of thousands of choices that lead the reader to them . . . Carrère’s true subject isn’t evil, but rapture, its precarious presence in our lives; how it disappears, how we become blind to it, how we seek it, how we become its prey and how, if we are fortunate, it at last catches up to us. However preoccupied Carrère is with loss and violence and pain, his books move to endings that earn a space of joy. They are, for lack of a better term, happy endings, but happy endings that feel not like tricks but truths. They are written by someone who knows precisely what they cost.”

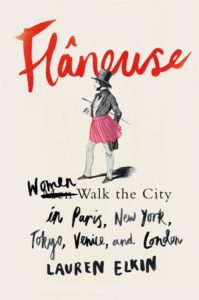

Lauren Elkin, Flâneuse

New Yorker Lauren Elkin moved to Paris in 2004, and learned the joy of urban walking, following in the footsteps of follows in the footsteps of Jean Rhys, Virginia Woolf, and George Sand.

Kathleen Rooney (Chicago Tribune) writes:

Throughout the pages of this erudite yet conversational book, Elkin sets about successfully persuading her audience that the joy of walking in the city belongs now—and has for ages belonged—to both men and women: “We can talk about social mores and restrictions but we cannot rule out the fact that women were there.” If anything, she suggests, “Perhaps the answer is not to attempt to make a woman fit the masculine concept, but to redefine the concept itself. If we tunnel back, we find there always was a flâneuse passing Baudelaire in the street.”

“A recurrent theme of Flâneuse is the pull between wandering and settling,” notes Heller McAlpin (Los Angeles Times), “illustrated most vividly with war journalist Martha Gellhorn’s story. Hemingway’s third wife, Elkin writes, ‘turned flânerie into testimony,’ but she ‘pinged between extremes’ of free-range activity and domesticity, often painfully.”

Diane Johnson (New York Times Book Review) concludes, “To be as good a flâneuse as Elkin also requires strong legs, sturdy feet, erudition and, above all, imagination, a way of being in touch with the ghosts who linger in recently visited spots. It will be up to booksellers to figure out how to categorize her pastiche of travel writing, memoir, history and literary nonfiction. A reader, flaneusing along the bookshelves, will find in it some of the pleasures of each.”

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.