5 Books Making News This Week: Athletes, Art, and Audacious Escapes

Gabe Habash, Percival Everett, Cate Lineberry, and More

Colson Whitehead and Matthew Desmond take a victory lap at the American Library Association annual conference in Chicago as fellow Carnegie Prize winners: Whitehead (fiction) for The Underground Railroad and Desmond (nonfiction) for Evicted. Both books also won Pulitzers this year; Whitehead’s won the National Book Award, Desmond’s the National Book Critics Circle award. Nick Laird’s third novel brings him back to his Northern Irish roots, Percival Everett’s So Much Blue “could not be timelier,” Teju Cole “brings the unseen realm of poetry into vision” in a hybrid blend of photographs and text, Cate Lineberry revives interest in a Civil War hero, and Gabe Habash’s first novel about a college wrestler is “one of the best sports books to come along in quite a while.”

Nick Laird, Modern Gods

Laird’s third novel brings him back to his Northern Irish roots, as he follows two sisters, one marrying for a second time in Ulster, the other traveling to a region he calls New Ulster in Papua New Guinea to work on a BBC film about a cargo cult. “I’d been reading about cargo cults for about 20 years,” Laird tells Michael Chabon in Interview. “The whole novel was arranged like a fever dream where you have these two separate realities—Ulster and New Ulster—and they end up having certain similarities.”

Modern Gods, writes Jennifer Egan (New York Times Book Review), “assumes the guise at various points of novels we’ve all read before: A man discovers he can’t escape the violent deeds of his past; a woman fed up with her life is spiritually revived by a visit to a third-world guru; a family reunion catalyzes the sharing of secrets and sorting out of misunderstandings. But this deeply ambitious book is none of those things, exactly—or rather, it is all of them and a great deal more. The characters in Modern Gods traverse oceans, time zones and political situations as part of Laird’s project to pry apart the very structures of worship and locate the systems they have in common, among them storytelling and ritual cruelty.”

“Laird’s ambitions and erudition deepen and nourish what, in lesser hands, may have been a pat story line,” writes John L. Murphy (PopMatters). “Having graduated from Cambridge before working six years in a London law firm, Laird adds to fiction his knowledge of how corporate charisma and capitalist machinations ensnare brash social climbers. While Modern Gods leaves the City’s financial heights to enter small-town Northern Irish and BBC media realms, it sustains Laird’s inspection of how aspirants to power get trapped in pain.”

Carlo Gebler (Irish Times) concludes:

Novels of ideas very often fail because, though the rhetoric may be marvelous, their literary virtue is deficient. Happily, this isn’t the case here. Modern Gods is an exceptional work of literature. It also fulfills its duty as a corrective to our collective idiocy by reminding us what we’ve forgotten: at bedrock, it says, we’re all just confused, lonely, yearning, terrified of death and desperate for love. If we’re to flourish as a species, the sooner we relearn this the better; so bravo, Mr Laird, for trying to help us to remember this.

Percival Everett, So Much Blue

Everett weaves together three stories, set in Paris, El Salvador and the U.S., as his midlife painter protagonist, an African-American abstract painter, works on a private piece that incorporates all the strands.

Everett’s new novel could not be timelier, notes Paul Devlin (The Nation), pointing to the controversies swirling around Dana Schutz’s Open Casket, a painting representing the murdered Emmett Till, which was displayed at the Whitney Biennial, Sam Durant’s 2012 sculpture Scaffold, which sought to comment on the mass executions of Native Americans in 1862 (it was dismantled and burned, following an agreement between the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis and the local Native community, before the exhibit even opened) and conceptual poet Kenneth Goldsmith’s reading aloud of a poem titled “The Body of Michael Brown,” in which he used text from the Ferguson teenager’s autopsy report.

“ . . . while a different culture’s history shouldn’t be declared categorically off-limits to an artist,” Devlin writes, “there are meaningful questions of quality, context, understanding, power, and purpose to be considered—and, along those lines, each work of art must be evaluated on its own terms. At least since his 1996 short story ‘The Appropriation of Cultures,’ in which an African-American man reimagines the Confederate Stars and Bars as a ‘black power flag,’ Everett has pondered this knotty subject, provoking a different set of questions: If the premise of cultural ownership is accepted, then what is left for the imaginative artist—to say nothing of the intergroup affinities that art has created and enhanced? What of those artists who don’t feel compelled to produce work that engages with the adversity or trauma that their group has faced? Social context exists, and often looms; it can be the catalyst or theme of profound art, but it doesn’t always have to be.”

“So Much Blue presents Everett, one of our culture’s preeminent novelists, a nonpareil ironist-satirist, turning away from the familiar terrain of his recent fictions,” writes Walton Muyumba (Los Angeles Times). “On this new turf, however, a problem arises for the author: Though ironic art may not lead the protagonist home, irony is a basic component of the kind of self-critique that will. Yet this crucial element—necessary to the character’s development and his realizations about secrets and art—is lost in the shuffle somewhat. Nonetheless, captivating and pleasurable, especially those pages devoted to El Salvador, So Much Blue is a ‘coming of middle-age’ story worth gazing into.”

Christian Lorentzen (Vulture) concludes, “There are echoes in So Much Blue of Don DeLillo’s The Names with the shadowy doings mingling with the story of a failed marriage, and of Alberto Moravia’s Boredom and its jaded painter-narrator. Americans dabbling in politics, drugs, bloodsport south of the border; an American indulging in faithless love in Paris; class posturing among Americans in Rhode Island—Everett has blended these disparate strands of an imagined life into a quietly beguiling novel. That he’s constructed it on an edifice of clichés, sanded down and transformed into combustive elements, is a sign of his mastery of the form.”

Teju Cole, Blind Spot

Cole, a novelist, essayist, photographer and photography critic for the New York Times magazine, offers up a hybrid book of photos and text that gives a full range of his introspective intellect.

A “questioning, tentative habit of mind, with its allegiance to particulars, suspending judgment while hoping for the brief, limited miracle of insight, drives Cole’s enterprise,” points out Robert Pinsky (New York Times Book Review). “It is an ‘avenue of thought’ for which he rejects ‘the dismissive term “self-referential.” ‘This inquiring, open attention is a form of what used to be called (before the word began to smell of departments and committees) ‘humanism.’”

“Blind Spot proves that Cole’s singular talents extend into picture-making, yes, but more than that, it shows what an extraordinarily gifted writer he is,” writes Jonathan Russell Clark (San Francisco Chronicle). “This may seem like a counterintuitive suggestion—this being a book of photos, after all—but Cole’s often brief commentaries function less like little helping-hand guides and more like an expertly executed and insightful narrative. These bite-size prose pieces are intricately structured, hauntingly written and add up to much more than the sum of their parts. Cole comments on his own work, of course, but he also examines photography as a whole; he tells stories from his journeys, as one would assume, but he also tells the stories of his subjects, of friends and family, of figures throughout history (from classic mythology to our tentative present); and he writes about what the images show, but he also focuses on what they do not.”

Ismail Muhammed (Slate) concludes:

Cole brings the unseen realm of poetry into vision, exposing a reality that’s not beneath the surface so much as caught in its interstices. “From time to time, in certain heightened states in certain individuals, the boundary between the chimeras seen in dreams and the discrete forms of waking life begin to blur,” Cole writes. “In these sudden rifts in the natural order of time, prodigies of vision in the guise of hybrid forms appear briefly.” He might as well be talking about this book: a hybrid form that deposits its readers into a heightened state of perception, a composite way of seeing that overcomes our blind spot. In this heightened state, the boundaries between a church in Lagos and a convenience store in New York blur and what you’re left with is the knowledge that they are inextricably linked, even if you don’t know how.

Cate Lineberry, Be Free or Die

Journalist Lineberry tells of Robert Smalls’ daring escape to freedom in 1862, when he commandeered a Confederate steamer and steered it to freedom—a Union blockade of Charleston harbor—and of his later years as a member of Congress. As Kirkus Reviews puts it, “An audacious paragon of the Civil War, now largely forgotten, is brought back to life, and his rags-to-riches adventure is certainly worth the revisit.”

“In writing Be Free or Die: The Amazing Story of Robert Smalls’ Escape from Slavery to Union Hero, journalist Cate Lineberry has done readers and history a good turn by chronicling the life of a man who led one of the most daring escapes from American slavery during the Civil War,” writes James McGrath Morris (Dallas Morning News).

Gene Seymour (USA Today) likens reading Be Free or Die to “recovering a national heirloom that was lost, stolen or buried through decades.”

Peter Lewis (Christian Science Monitor) notes:

Smalls’s story is dramatic enough, but Lineberry gives it greater honor by setting it in the context of its surrounding circumstances. It doesn’t take any particular imagination to understand that the Civil War did not erase the institutionalization of racism in this country or even, for that matter, end slavery. But it is mostly students of the period who appreciate the hurdles that African-Americans experienced at nearly every turn.

Lineberry goes deeper. She pulls apart Lincoln’s Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction, which encouraged helping freemen gain education and work, but had no teeth to enforce compliance.

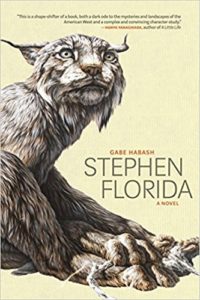

Gabe Habash, Stephen Florida

Habash’s first novel follows the final months of his narrator’s college wrestling career. Why wrestling? “I really only love basketball,” Habash tells Jonathan Lee at the Paris Review. “LeBron James is the greatest human being on the planet. But what drew me to wrestling was how demanding and unforgiving it is.”

“This is a sports novel for everyone,” Isaac Fitzgerald tells his Today Show viewers. “It’s a fantastic read, because it’s such a compelling character. If you are a human being who’s had drive, this is a book for you.”

“The moments when he is on the mat are the book’s best, delivering a near-perfect combination of lyricism and clinical detachment,” notes Lucas Iberico Lozada (Paste).

“Stephen Florida is brash and audacious,” writes Michael Schaub (NPR). “It’s not just one of the best novels of the year, it’s one of the best sports books to come along in quite a while. It’s an accomplishment that’s made all the more stunning by Habash’s status as a debut novelist: It’s his first time on the mat, and he puts on a clinic.”

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.