5 Important Books That Reveal the Human Cost of War

Janine di Giovanni on Influential War Reportage

As a reporter, I’ve documented war and conflict for more than three decades. The things I carry with me are important. While traveling light and often working in closed countries or besieged areas, the most important things in my backpack, aside from a medical kit, is a book that can nourish and inspire me. Many of the classics of war reportage I chose also parallel with my own life and professional experiences.

Martha Gellhorn, The Face of War

(Grove Press)

Over the Christmas of 1992, at night in my freezing unheated room on Sniper’s Alley, I burrowed under my sleeping bag in three layers of clothes with a flashlight, a candle, and Martha Gellhorn. I was frightened, hungry, cold, and disoriented—besieged Sarajevo was my first real war—and I took some comfort knowing another woman had gone long before me, also struggling to convey the political complexities of a multi-faceted war along with the gut-wrenching sadness of the destruction of a society.

My literary masters had always been the Russians—Turgenev, Chekhov—but Gellhorn’s book, which starts with the Spanish Civil War and winds its way into World War II and beyond, was my solace and my guide, my introduction to the genre of literary reportage. The Face of War taught me, in some ways, that reporting war wasn’t about news angles, but in attention to details—what the aftermath of a bombing smelled like and felt like, how people cut down trees in the park to stay warm or made bread out of rice from humanitarian aid packages. In later life, I met Gellhorn several times. I didn’t agree with her views—she was fiercely anti-Palestinian, based on a few weeks in 1960 traveling through UN refugee camps. For a woman whose early work was full of empathy, her unfailing support of Israel at any cost was entirely partisan and biased. Still, I will never forget reading The Face of War for the first time, marking it lightly with a pencil, and coming back over and over to re-read it during the dark and frightening Bosnian nights for inspiration.

Artyom Borovik, The Hidden War: a Russian Journalist’s Account of the Soviet War in Afghanistan

(Grove Press)

I was in Grozny during the second Chechen war when it fell to Russian forces and remember the terror of constant aerial bombardment, the freezing cold, the blood sticking to my boots, the screams of soldiers as their limbs were amputated. Chechnya was the most dangerous and probably frightening war I ever reported, and I struggled to contain my own fear. The Hidden War was always with me. The late Russian journalist Borovik was a beautiful, poetic writer who grasped the ultimate sadness of war—and how the dead come back and haunt you long after you leave the battlefield.

Bao Ninh, The Sorrow of War

(Anchor Books)

In 1995, 20 years after the fall of Saigon, I arrived in a bleak Hanoi housing project to meet this gifted writer. He had been among the child soldiers during the Vietnam War on the Ho Chi Minh Trail and it marked him forever. By the war’s end, most of his fellow soldiers were dead. I was haunted by his lyricism, his stirring passion, his quiet and desperate sadness.

Elliot Paul, The Last Time I Saw Paris

(Crombie Jardine)

After many years in Africa, the Balkans, and the Middle East, I moved to Paris in 2004 to marry and have a baby boy. I struggled to adapt to “normal” life and tried to write about the long-term effect of war. I was intrigued by the occupation of Paris—my own family, like many French families, had both resistance fighters and those who kept their heads down to stay alive during the Nazi occupation. Elliot Paul, an American reporter, lived in Paris on the Rue de la Huchette between the two wars and recorded the everyday life of everyday people—the iceman, the sex workers, the butcher, the baker. He stayed until shortly before they were either sent away, one by one (many were Jews). He returned, postwar, to see this ghost of a neighborhood. It’s a forgotten jewel of a book, a wonderful reminder of how war causes things to fade and disappear—never to return to what they once were.

Rebecca West, Black Lamb and Grey Falcon

(Penguin Group)

Between the two world wars, Rebecca West took a journey to Yugoslavia. Like me, she found herself under the magical Balkan spell. Her portrayal of the country before it cracked into a million pieces is often hard going, but it’s well worth the time and energy to read it. Having spent most of the 1990s in the Balkans, to me, there is no finer interpretation of the people and the region.

__________________________________

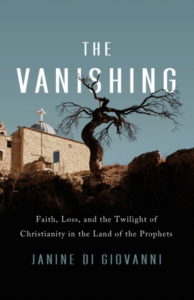

The Vanishing by Janine di Giovanni is available via PublicAffairs.

Janine di Giovanni

Janine di Giovanni is the winner of a 2019 Guggenheim Fellowship and in 2020 was awarded the Blake Dodd Prize from the American Academy of Arts and Letters for her lifetime achievement in non-fiction; it has previously been awarded to Alexander Stille and Elizabeth Kolbert. She has won a dozen other international awards. She is a Senior Fellow at Yale University, the Jackson Institute for Global Affairs and the former Edward R. Murrow Fellow at the Council on Foreign Affairs in New York. Her accolades are well-deserved; she has written and reported from the Balkans, Africa and the Middle East, where she witnessed the siege of Sarajevo, the fall of Grozny and the destruction of Srebrenica and Rwanda in 1994, as well as more than a dozen active conflicts.