5 Artists Who Explore Japanese-American Incarceration and Internment

Brandon Shimoda on Heather Nagami, Rea Tajiri, Aisuke Kondo, Brynn Saito, and Kevin Miyazaki

By the time I was old, more importantly conscious, enough to ask my grandfather questions about his life, he was dead. And he had been dying a long time before that. He had Alzheimer’s for 15 years (or 10 or 20 or 12 years, depending on who you ask). He died at 86. I was 18. Among the questions I would have wanted to ask him were about his time as an “enemy alien” of the United States, including his incarceration in a Department of Justice prison in Missoula, Montana. (Internment is used to define the detention of non-citizens, incarceration the detention of citizens, but because my grandfather was, as an Asian immigrant, ineligible (until 1952) for citizenship, I use the word incarceration to emphasize the impossibility of his situation.)

My grandfather, Midori Shimoda, was born on an island off the coast of Hiroshima and immigrated to the United States when he was nine. He spent the second half of his childhood in Seattle, and then was living and working as a photographer in Pasadena in 1941, when Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor validated and made legal what had already been established as the white population’s decades-long war against Asians in America. My family rarely, if ever, talked about the past; my only recollections of hearing about Japanese-American incarceration were of stories cast in primary and ultimately conciliatory colors. Other members of my family, including two great-aunts, my great-uncle, and their children, were also incarcerated.

It was not until my grandfather died that the loss of his memory fully exposed the enormous vacuum in our family’s history, as well as my lack of understanding about what Japanese Americans endured before, during, and after Executive Order 9066—signed by Democrat FDR—forcibly removed them from their homes and incarcerated them in remote concentration camps throughout the United States. My grandfather’s death occasioned a reckoning.

I began to read towards an understanding of his experience, through the experience of others, in books by former incarcerees: Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston’s Farewell to Manzanar, John Okada’s No-No Boy (the University of Washington Press edition, the only legitimate edition), Yoshiko Uchida’s Desert Exile, and in poems by Lawson Fusao Inada, Janice Mirikitani, and Mitsuye Yamada.

In 2005, while a graduate student (studying poetry) at the University of Montana—down the road from where my grandfather was incarcerated—I received a review copy of a book of poetry that introduced me to a perspective that I had, for reasons ranging from self-consciousness to ignorance, taken for granted: that of the descendants, those who were not there. The book was Hostile, by Heather Nagami, yonsei (fourth generation). Its revelation was that the experience of incarceration, and the story about the experience, was not over, but ongoing, and that the descendants’ perspective—formed out of the work of re-inhabiting and re-enacting and reclaiming and rehabilitating their forebears’ experiences—was fully a part of it, was the next phase. I have taken to calling this next phase, which is the current phase, the ruins.

The following is a narrative list of five descendants of incarceration (two poets, one filmmaker, one artist, one photographer) whose work reports directly from—and proliferates—the ruins of Japanese-American incarceration, and is meaningful to me and my work. Five is an arbitrary number. Absent from this list are other writers and artists whose work is meaningful to me and mine, especially Karen Tei Yamashita, whose book Letters to Memory (Coffee House Press, 2017)—a multifarious documentary immersion into her family’s history—is one of the great panoramic works on the afterlife of Japanese-American incarceration, and one on which I hope to someday write. For now, may this passage act as a guide:

As for history, you note the historian’s problem that writing about an event is not the same as living it. History is an inquiry, and there is an attempt here to, as you say, clear the ground with these letters, meaning perhaps to properly bury the dead. Yet even so, you say, we are rendered speechless, dumb, when it comes to the hearts. There are, you agree, things beyond history, which history may point to yet also obscure. Beyond or behind history are glimpses of what matters.

Heather Nagami, Hostile

Heather Nagami, Hostile

Nagami’s parents and grandparents were incarcerated in Poston. Her mother was born there. Her birth is announced in the first line of the first poem of Hostile, “Acts of Translation”: “’I was born in a hospital,’ she tells me, proudly (Figure 10.57), ‘driven out of the camp to a hospital’ (Figure 10.57).” There is no Figure 10.57, by the way, at least not in the book. Poston is not reimagined—in the book, or in the poem—so much as it is permitted to exist in its present state of erasure and decay.

When I first read the poem, it struck me that Nagami was, in this way, breaking with the tradition of projecting onto the ruins the more efflorescent and redemptive aspects of family lore. There is neither redemption nor epiphany nor lyric consolation. There are no flowers. There is inquiry, uncertainty, frustration, and doubt. There is a desire to understand, and the despair that greets any genuine effort to communicate with the dead.

“Acts of Translation” cites Confinement and Ethnicity, a historical text combining site visits and first-person testimony. In a series of dialogues that are revelatory in their skeptical and alienated, yet desperate and flirtatious relationship to the historical record, the poem talks back to the book, talks back to the voices that emerge from the history the book both reveals and constrains, talks back to the languages the voices speak, talks back to its own attempts to understand a language from which it has been forcibly removed, talks back to the poet’s attempts to identify herself within the dissolving frames of all the above.

I heard Nagami read “Acts of Translation” in Tucson (where I live, where she used to live) on February 19, 2017, the 75th anniversary of the signing of Executive Order 9066. Nagami’s mother was in the audience. Half way through the poem, Nagami’s voice cracked, and she stopped reading. She stared into her poem like she was searching for her face in a mirror. I say her voice cracked, but she cried. 12 years had passed since “Acts of Translation” had come out, but its desire and despair were still ongoing.

Rea Tajiri, History and Memory: for Akiko & Takashige

Rea Tajiri, History and Memory: for Akiko & Takashige

Rea Tajiri, Strawberry Fields

Rea Tajiri, Strawberry Fields

Tajiri’s parents and grandparents were incarcerated in Poston. History and Memory is a short, speculative documentary film. Strawberry Fields is a feature-length fiction film. They are companion pieces, and two of my favorite films. Both are immersions into the fog of Tajiri’s family’s incarceration, and are expressions of the descendant’s attempt to understand the inheritance of those experiences. Both films are motivated—haunted, inspired—by images. “I just had this fragment, this picture, that’s always been in my mind,” Tajiri says, in History and Memory,

my mother, she’s standing at a faucet, and it’s really hot outside, and she’s filling this canteen, and the water’s really cold, and it feels really good, and outside the sun is just so hot, it’s just beating down, and there’s this dust that gets in everywhere, and they’re always sweeping the floors.

The film proceeds, from there, to re-enact this fragment, enfolding it into a meditation on representations of history: personal, collective, filmic, propagandistic.

In Strawberry Fields, the main character (Irene Kawai, sansei, 16, played by Suzy Nakamura) discovers a photograph of her grandfather standing in front of tarpaper barracks. The discovery initiates a simultaneous unraveling and sharpening of Kawai’s understanding of her family’s history, including their incarceration. Strawberry Fields is revelatory for (at least) three reasons: it features an entirely Asian-American, primarily Japanese-American, cast; it is the only feature-length film about Japanese-American incarceration that does not center a white love interest/savior (e.g. Dennis Quaid in Come See the Paradise, Ethan Hawke in Snow Falling on Cedars); and it is the only feature-length film that centers the perspective of a descendant of incarceration. Not only that, but Kawai’s perspective—born out of her parents’ and grandparents’ trauma—is inflamed with confusion, frustration, and anger.

It is the perspective of intergenerational trauma, fresh and unrelieved. The scenes that take place in the ruins of Poston—which feature a joyous yet heartbreaking performance by Takayo Fischer—are perfect in how they articulate the empowerment and isolation, the turbulence and peace, one feels in the ruins, but especially in their lack of resolution.

Aisuke Kondo, here where you stood

Aisuke Kondo, here where you stood

Kondo’s great-grandfather was incarcerated in Topaz. Kondo (the great-grandson) was born and grew up in Japan, and is currently based in Berlin. After a year or so of corresponding, we met in person this year; we presented our work together at the Poetry Center at San Francisco State University. Kondo told a story about how he was cleaning the hair (blond) out of a shower drain in a hostel in Berlin when he became dizzy and had a flash of his great-grandfather cleaning houses, years earlier, in San Francisco. In that moment, some kind of ancestral transference took place. Kondo felt like he was re-enacting his great-grandfather’s life as an immigrant.

Much of Kondo’s work is devoted to uncovering the truth and consciousness of his great-grandfather’s experience. One of the films he showed was here where you stood, in which he visits the ruins of Topaz. The film is short, six minutes. I keep thinking about what happens four minutes in. Kondo, wearing a black hoodie and carrying a cane, walks down a deserted road, then stops and starts swinging the cane at the air, as if beating the air with it, until, at the end, he breaks the cane on the ground. It was an accident. Kondo did not mean to break the cane. I became quite emotional, he said in an interview. The cane was his great-grandfather’s. His great-grandfather made it while incarcerated at Topaz.

I keep thinking about it, because what do you do when you arrive, after generations have passed, in the place, on the land, where your ancestors were dehumanized?

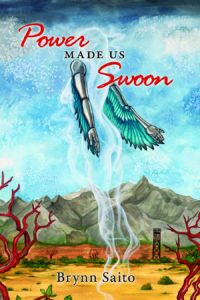

Brynn Saito: Power Made Us Swoon

Brynn Saito: Power Made Us Swoon

Saito’s grandparents were incarcerated in Gila River. Her aunt was born there. My introduction to Saito’s poetry was through her poem “Alma, 1942,” which appears in The Palace of Contemplating Departure. It ends with these lines:

You’ll see it for yourself

when you go there roving

with your questions for the barracks

like a hungry ghost.

A simple yet astounding realization, and one that has shaped my research: that we can ask questions directly of the ruins. Saito’s poetry provokes, in me, and provides me with, the questions, or kinds of questions, I too want to ask of the ruins. In her poem “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Teacher Resource” (which is in the March 2019 issue of Evening Will Come), she asks (and answers) a series of questions, including: What types of memories have you inherited? What are the differences between memory and history? How do you make meaning from the past? She answers the last one like this:

See the writer again at the gate of memory?

See the writer again—

See the writer again at the gate?

Gate the writer again at the memory—

Gate the writer—

See the past again at the meaning gate?

Past the meaning—

Past the making, gate the memory—

See the meaning?

She should drown it.

The question, See the writer again at the gate of memory? also appears in her second book, Power Made Us Swoon; it is the first line of the poem “Stone on Watch at Dawn.” The poem also includes the line, “She should drown her pages / in the sky,” an action and image she revised in “Thirteen Ways.” I appreciate her pages and the sky, and I also appreciate their disappearance in the subsequent poem. But most of all, I appreciate Saito’s inclination to return to those lines, to weave them into the form of an exam, because it reveals the fact that the lines with and through which a poet thinks are not necessarily relieved by their inclusion in a poem, but continue to rattle, sometimes restlessly, in search of a place, more specifically a way of being.

The second section of Power takes place in the ruins; Saito’s poetry affirms the ruins as a place where confusion, doubt, anger, and love, are supported and consoled, and by the voices that make it a space of transgenerational resonance. She is also the cofounder, with Nikiko Masumoto, of the Fresno, California-based Yonsei Memory Project, which utilizes arts-based inquiry to generate dialogue connecting Japanese-American incarceration with current and ongoing civil liberties struggles.

Kevin Miyazaki, Camp Home

Kevin Miyazaki, Camp Home

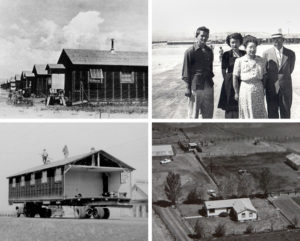

Miyazaki’s father and grandparents were incarcerated in Heart Mountain and Tule Lake. His grandfather was also incarcerated (with my grandfather) in Fort Missoula. Miyazaki, a photographer, has made a variety of work about Japanese-American incarceration, from posters to books to a Relocation Welcome Kit consisting of bucket, broom, handkerchief, hammer, hooks, nails, among other practical items. The work I keep returning to is Camp Home, a series of photographs of houses, barns, and buildings in Northern Wyoming (near the ruins of Heart Mountain) and Northern California (near the ruins of Tule Lake).

What the buildings have in common is that they are all or partly made from the concentration camp barracks. After WWII, the United States government created a lottery-based homesteading program for veterans. The vets, primarily young men, some of whom had families, were given land and houses constructed of repurposed barracks. And with that, one of the many overlapping circles of colonization was complete. The barracks—infused with the soul and spirit of the Japanese-Americans—were given new life within the hallucination of umpteenth generation Manifest Destiny. Miyazaki’s photographs are of interiors and exteriors. Houses, roofs, rafters, siding, shingles, cabinets, walls. Especially walls. Plates on walls, hats on walls, guns on walls, tools and utensils on walls, and framed photographs on walls. The framed photographs are all of white people, smiling.

It was racism that motivated the mass incarceration of Japanese immigrants and Japanese-Americans. Racism, rage, white anxiety over land haunted by its having been stolen. Miyazaki’s photographs are beautiful. Their revelations are plainspoken. Yet clear. To be confronted, through them, with the absurdity of war veterans—many of whom served, against the Japanese, in the Pacific—converting the former prison quarters of the Japanese-Americans, into homes, and the manifestations of their dreams, is bitter, absurd, comic, profound, and: of course! Yes, the story of Japanese-American incarceration—or one story among many—has always been about theft masquerading as renewal.

_________________________________________

Brandon Shimoda’s The Grave on the Wall is out now from City Lights.

Brandon Shimoda

Brandon Shimoda is a yonsei poet/writer, and the author of several books, most recently The Grave on the Wall (City Lights, 2019), which received the PEN Open Book Award. He has two books forthcoming: Hydra Medusa (Nightboat Books, 2023) and a book on the afterlife of Japanese American incarceration (City Lights, 2024), which received a Creative Nonfiction grant from the Whiting Foundation.