30 Books in 30 Days: Mark Athitakis on Ottessa Moshfegh's Eileen

Counting Down the National Book Critics Circle Awards Finalists

In the days leading up to the March 17th announcement of the 2015 NBCC award winners, NBCC’s blog, Critical Mass, will be highlighting the thirty finalists with critical appraisals—we’re happy to be running those concurrently here at Literary Hub. Today, NBCC board member Mark Athitakis offers an appreciation of fiction finalist Ottessa Moshfegh’s Eileen (Penguin Press).

Mark Athitakis on Ottessa Moshfegh’s Eileen

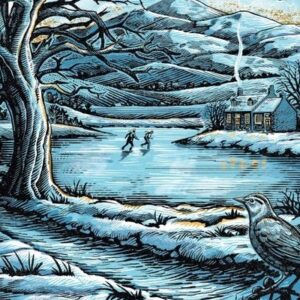

Ottessa Moshfegh’s novel Eileen takes place in 1964 in a New England town that its narrator calls X-ville. In the context of the story that follows, that “X” reads like a slash, a barring, a negation, a transgression, an urge to expunge. We know going in that something bad has happened to its protagonist, but we also know she’s survived it; she’s writing from a distance of decades. So how’d she’d get through? The entire book is the long answer, but the short answer comes early—she’s psychically split herself in two. “I was not myself back then,” she writes. “I was someone else. I was Eileen.”

To put it another way, X-ville is also Unreliable Narrator City. Unquestionably, Eileen’s life is hard. She lives in a home in which she cares for a desperately alcoholic father. She works as a secretary in a boys’ prison, a dreary place soaked in error and violence. She imagines suicide with a blunt, clinical implacability that signals a host of problems: “People died all the time,” she muses. “Why couldn’t I?” The arrival of a new coworker, Rebecca, at first suggests a way out, but for Eileen it also unlocks a mix of romantic obsession, bad behavior, and despair.

Easy reading is hard writing, the saying goes, and the plainspoken clarity of Eileen’s prose is a testament to Moshfegh’s talent. But this simplicity cloaks multiple psychic layers. Moshfegh is superb at hinting at the one-eyelid-twitching aspect of Eileen’s character while keeping her sentences free of unearned portents, and while preserving our concern for Eileen’s fate.

The “loud, rabid inner circuitry” of Eileen’s mind carries echoes of Shirley Jackson or Patricia Highsmith’s The Price of Salt, while evoking the bleak New England of Russell Banks and women-in-trouble stories of Joyce Carol Oates. Eileen is a study in how a place can make you feel trapped. But it’s also an interior story about living with self-disgust, which is why Moshfegh makes her story at least a little repulsive—candid descriptions of body functions abound, and Eileen glories in them. (“My little world of exhaust and vomit was somehow wonderful.”)

As much as any recent novel, Eileen explodes the notion that an affecting, well-made character must be a likable one. But even readers who recognize the likability fallacy will be provoked by Eileen, a superbly crafted and imagined novel about the difficulty of escaping the place where you are, and what the place has turned you into.

Read Tobias Carroll’s profile of Ottessa Moshfegh here.

Mark Athitakis

Mark Athitakis is a writer, editor, critic, and blogger who’s spent more than a dozen years in journalism. His work has appeared in the New York Times Book Review, Washington Post Book World, Chicago Sun-Times, Minneapolis Star-Tribune, Washington City Paper and many more publications.