Somehow, it’s fall again: cue mugs of tea, the return of socks, and all the biggest books of the year. As always, if you’re trying to figure out which books to read this season, Literary Hub has got you covered. Here you’ll find a list of the novels hitting shelves over the next three months that our editors have read and loved, and think you might just want to read too. Enjoy curled up on a couch somewhere, as the leaves fall gently outside . . . or perhaps in the continued blazing sun of our planet’s new eternal summer. Either way.

*

Maggie O’Farrell, The Marriage Portrait

Knopf, September 6

For those of us who loved Hamnet, Maggie O’Farrell’s stunning novel of Shakespeare’s wife and family, we are in luck: The Marriage Portrait is a similarly beautiful and excavating tale of a forgotten character, in this case Lucrezia de’ Medici. O’Farrell seems to have found her niche: fictionalizing the life of a 16th-century woman whom history has deemed lost to time. The Marriage Portrait is a book based on a poem, which was based on a painting, which was, once upon a time, based on a real woman, the 15-year-old Lucrezia de’ Medici as she was marrying Alfonso, Duke of Ferrara. What is known about Lucrezia is this: she was 15 when she married Alfonso, and she died a year into their marriage. Though the official cause of death was pulmonary tuberculosis, it was rumored that she died at the hands of her husband.

O’Farrell takes this rumor and runs, spinning a tale so lush and evocative and gaudy the whole narrative has a texture of velvet and encrusted jewels. It’s true that one has to be ready for elaborate language: it’s one of the more ornate texts I’ve read in a while, but the effect is fairy-tale-esque, with beasts and saviors, unexplainable magic, and last-minute happy endings. This is historical fiction at its best. O’Farrell knows the truth is dark, vast and unknowable, so she gives us something even better than the truth: a richly detailed, richly imagined, richly unbelievable story.

–Julia Hass, Contributing Editor

Hanne Orstavik, tr. Martin Aitken, Ti Amo

Archipelago, September 13

To read Hanne Orstavik is to submit to the harder truths of life—chief among them, of course, the inevitability of death. Like her 2018 novel, Love, also published by Archipelago, Ti Amo unspools with the cool urgency of early Marguerite Duras, as if it were a story that could only be told in one, long impossible exhalation (it’s no surprise that Orstavik namechecks Duras in Ti Amo).

If autofiction exists, Ti Amo—ostensibly a novel—is it. Written in the second person it can be read as a kind of love letter/confession to Orstavik’s late husband who—like the unnamed addressee in Ti Amo—was Italian, and who died of cancer. Orstavik’s compulsive candor, her brutal honesty about her all-too human needs, is leavened throughout by a matter-of-fact tenderness for life and the world; as deeply—and necessarily—sad as it is, Ti Amo is lit from within by this tenderness, by this love. To be specific, this love:

You, with whom I belong. You, who make the night and the darkness our own, in our big bed, a place where I can touch you, sense that you exist, and feel secure. You, who are home to me, my sky.

Ti Amo is to be read in its entirety on a late fall Sunday afternoon as the coffee turns to wine.

–Jonny Diamond, Editor in Chief

Gwendoline Riley, First Love

NYRB, September 13

Neve is a writer in her 30s, riding through a roller coaster of a marriage. One minute, Edwyn is calling her by their peculiar pet names (“little cabbage”) and the next, he’s declaring he has no intention of spending his life with a shrew. So much of what’s incredible about this novel is the precision of the dialogue. There are so many lines like daggers that cut under the surface of their relationship: “Love for you is possession, isn’t it?” Or, on the subject of saying “I love you” : “No, you only say that in order to be told it back. You know that.”

So how, exactly, did Neve end up in this place? There’s a line in this book that goes: “In Russia if you say you fell in love at first sight, it translates as ‘I fell down.’” Down the rabbit hole we go. In First Love, Gwendoline Riley takes us on a tour through Neve’s past/psyche to help us understand her specific plights. We meet her horrible father; her hilariously chatty, self-absorbed mother; and the musician that was her first big heartbreak. (“I don’t think I can think of you… outside of the context of—loving you?” is something he says to her at some point, and who among us has not fallen for that?) It’s a gutting rumination on the way our ghosts act out in our current relationships. I tore through this slender novel in a single afternoon, and it felt like reliving the worst, most whiplash-inducing fights you could imagine with a lover (in a fun way).

–Katie Yee, Lit Hub associate editor

Andrew Sean Greer, Less is Lost

Little, Brown, September 20

Returning to a beloved fictional world is always a pleasure, but to return and find the world’s characters, humor, and humanity deepened is a rare treat. Such is the case with Andrew Sean Greer’s follow-up to his Pulitzer Prize-winning Less. Less Is Lost shares a narrator, Freddy Pelu, with the first novel, though where in Less the narrator’s identity was mysterious until the novel’s end, now Freddy is known to us as Freddy—partner of the (still charmingly dizzy) Arthur Less. After the death of Less’s ex, the poet Robert Brownburn, puts Less on the hook for ten years of back rent (at San Francisco market prices!) on Robert’s house—where he and Freddy live—Less embarks on a series of writing gigs across the country to earn the money to dig himself out. (With a pug named Dolly, in a camper van named Rosina, naturally.)

Greer’s balance of razor sharp wit with genuine warmth makes this book a welcome balm at a moment when balms are in short supply. It’s a true charmer I recommend to anyone looking for an escape from (a truly charmless) reality.

–Jessie Gaynor, Lit Hub senior editor

Chelsea Martin, Tell Me I’m an Artist

Soft Skull, September 20

I love a campus novel in the fall, but I would reread Chelsea Martin’s Tell Me I’m an Artist any time of year. Joey is in her second year of art school in San Francisco, three hours from where she grew up, though it might as well be another universe: her peers are wealthy and well-connected, assured that they’re where they belong. Meanwhile, Joey is poor—and not just I Feel Bad About Much I Spend On Takeout poor, but When The Student Loans Dry Up There’s Literally No More Where That Came From poor.

She doesn’t tell her closest (and only) friend that she’s on the verge of being evicted from her apartment, and she spends the entire semester thinking about—but not really working on—a self-portrait in the form of a remake of a Wes Anderson film she’s never seen. Also, her older sister has gone missing and left her toddler with their mom, and Joey feels guilty that she’s not more help to her family and guilty that she doesn’t actually feel more guilty. She wants a new kind of life, one her mom and sister might find frivolous and even privileged, and she doesn’t know if she deserves it. The stakes are HIGH.

If you can’t relate to the poor stuff, don’t worry—there’s also a lot of poignant (and amusing) musings about what it means to be an artist, some of which come in the form of hand-drawn Venn diagrams. (My personal favorite: “art” in the left circle, “self-respect” in the right, “something probably goes here” in the overlapped middle.) Also, over the course of the book, Joey learns some very important truths about friendship. Yes, all of that happens in the same book! And it doesn’t feel overwrought! Now that’s a work of art.

–Eliza Smith, Special Projects Editor

Yiyun Li, The Book of Goose

FSG, September 20

It would be reductive to describe this novel as Elena Ferrante meets Fleur Jaeggy, because of course Yiyun Li is a master with a style all her own—but it’s tempting. It concerns two friends in the French countryside—one hard and brilliant, the other our narrator, as is often the way—who decide to write a book. The book they write is disturbing, and it vaults our narrator to fame, which complicates their already obsessive and strange relationship, brought to the surface by Li’s magical prose, sharp as a knife and also somehow dreamy, like an almost-bitter elegy. I loved it.

–Emily Temple, Managing Editor

Stephanie LaCava, I Fear My Pain Interests You

Verso, September 27

I Fear My Pain Interests You is a book that gets under your skin, whether or not you want it to. LaCava’s narrator is a cool, disaffected twenty-something, the child of famous (and troubled) musicians, who also has been unable to feel physical pain since childhood. After being kicked out of college, and while recovering from a romantic liaison with a horrendous man, she skips town to stay in her friend’s fancy digs in Montana. There, she meets a doctor whose morbid fascination with her condition tips the scales very, very far into creepy. Understated and elegant, LaCava’s writing inspires both dread and longing; her characters, nearly all of them direct to the point of cruelty, also seem unable to say anything that would lead to real emotional connection. The horrors of this book build so subtly that their apex seems both unfathomable and inevitable, like a deep fear that finally comes to pass. Still, I’m not sorry for bearing witness to this striking story.

–Corinne Segal, Lit Hub senior editor

Laura Warrell, Sweet, Soft Plenty Rhythm

Pantheon, September 27

At the center of Laura Warrell’s deeply engaging multifocal debut novel is a familiar figure: he’s charming, emotionally withholding, as rakish as he is readily wounded, and cursed with just enough talent to keep the dream going long after it should. In this case, his name is Circus Palmer, a 40-year-old, womanizing jazz trumpeter who may or may not be on the downslope of a career that never quite had an upslope.

A character like Palmer could easily come across as pathetic, a toxic joke to everyone but himself (and whoever happens to love him at any given moment), but Warrell let’s us see Palmer through the eyes of all those women—lovers, friends, a teenage daughter—whose lives he’s upended one way or another. And rather than each viewpoint serving as further damning evidence of Palmer’s egocentric selfishness, they instead offer glimpses of his increasingly human frailties.

In this way the novel is built like a hastily assembled jazz ensemble, a group of players taking turns on a rough theme, gathering their solos into a rich, indelible composition, so much stronger than the sum of its parts.

–Jonny Diamond, Editor in Chief

Namwali Serpell, The Furrows

Hogarth, September 27

This knottily brilliant puzzle box of a novel from Namwali Serpell (The Old Drift) is an aching, stylistically innovative portrait of grief, memory, and familial fracture that is already earning its author comparisons to Toni Morrison. The eldest child of a black professor father and a white artist mother, Cassandra Williams looks back—over and over and over—on the day her beatific 7-year-old brother Wayne drowned (or was he killed in a car crash? Or a bizarre fairground accident?) and then disappeared (to where, and with whom?). In the wake of the tragedy, Cassandra, “C,” cycles through talk therapists while her taciturn father moves to Georgia to start a new family and her broken mother builds Vigil, a foundation dedicated to “missing” children. As C gets older, and grudgingly begins working at Vigil, she starts to see Wayne in the faces of strangers, saviors, lovers—one of whom is pursuing his own secret agenda. A surreal, sensual, and often thrilling examination of childhood trauma and its devastating ripple effects, this is a novel destined to end up on every Best of the Year list.

–Dan Sheehan, Book Marks Editor-in-Chief

Elizabeth McCracken, The Hero of This Book

Ecco, October 4

“What’s the difference between a novel and a memoir? I couldn’t tell you. Permission to lie; permission to cast aside worries about plausibility.” So writes Elizabeth McCracken in her new novel (?), The Hero of This Book. (Personally, as a lover of memoir, I don’t take much umbrage with memoir-disguised-as-fiction, if for no other reason than it allows me to read and write about them for our novel lists.)

Anyway, the narrator of this novel is walking around London and thinking about her mother, who died ten months prior; she’s thinking about flaneurs and accessibility (her mother used canes and a wheelchair—at one point, the narrator realizes she could’ve taken her mother on the London Eye after all and wonders, Is this grief?); she’s thinking about privacy and authorship and the ways we keep others at a safe distance. It’s a beautiful, unusual book—a sort of meditation—elevated by McCracken’s playful relationship with language, and it left with me with the distinct conviction that no daughter has ever seen so clearly that mysterious and forever-looming figure that is her mother.

–Eliza Smith, Special Projects Editor

Hiroko Oyamada, tr. David Boyd, Weasels in the Attic

New Directions, October 4

Is there anything more satisfying than a slim, perfectly constructed novel(la) you can read in an afternoon? Hiroko Oyamada’s latest is a wonder of narrative economy and quiet suspense. The novel follows its narrator across three strange evenings with his friend Saiki over a number of years. Looming anxiety swirl through these chapters—anxiety about fertility, masculinity, marriage, and hunger, as well as a dread which is never named, but which kept me both profoundly unsettled and completely glued to the page. The magic of this book is in its deft melding of the real and the surreal. It has the tension of great horror, but the actual horror is subtle and elusive—fish flakes as both a dinner party appetizer and an act of charity; a story about the best way to rid your home of the titular weasels. I was entirely enthralled as I read it, and I haven’t been able to stop thinking about it since.

–Jessie Gaynor, Lit Hub senior editor

Celeste Ng, Our Missing Hearts

Penguin Press, October 4

What an immense joy it is to be back in the trusty hands of Celeste Ng! Like Little Fires Everywhere and Everything I Never Told You, Our Missing Hearts is a careful study of a family trying their best to live their lives in a world that is rooting against them. In this dystopia, the government’s top priority is “preserving American culture” in the name of “keeping peace.” The xenophobia has run amok, particularly against those of Asian descent. Children are taken away from parents suspected of treason. Books with views that don’t align with the government are removed from shelves and destroyed. (Sound familiar?)

This is particularly hard on Bird, a 12-year-old biracial boy whose Chinese American mother was a renowned poet but who left the family three years before this story begins. His linguist father thinks ignoring Bird’s Chinese roots will keep him safe. They do not discuss his heritage, or his mom. Bird can’t find a single trace of her writings in the university library where his father works—but the novel begins when he receives a cryptic note in the mail. Well, not so much a note as a doodle of cats. It’s got to be from her, and it’s got to be a clue.

On top of that, there are all these odd pieces of art cropping up, much to the dismay of law enforcement: a tree covered in yarn with knitted children tied to it, graffiti that speaks of missing hearts—an allusion to his mother’s book. So begins Bird’s journey: into his memories of myths his mother used to tell him, into back rooms of libraries where old card catalogs are a reminder of all that we’ve lost and the power of language.

The story is told in close to third, and what’s particularly striking is Celeste Ng’s ability to show us the horrors of this world while also showing how banal it’s become for our characters. (Even the language in Bird’s math homework exemplifies a deeply-embedded racism.) This is a tale that is propulsive and poignant in equal measure; it’s a much-needed love letter to the written word.

–Katie Yee, Lit Hub Associate Editor

Erin E. Adams, Jackal

Bantam, October 4

As Jackal begins, Liz Rocher has reluctantly headed home to Johnstown, Pennsylvania for her childhood best friend’s wedding. She’s prepared for the micro-aggressions from her friend’s racist family, but during the celebration something far worse happens—a beloved child goes missing, and the key to her disappearance stretches back over decades of missing children, all of them young Black girls last seen around the summer solstice.

Meanwhile, a spirit in the woods is close to taking corporeal form and rejecting the bonds of its human master. A social thriller perfect for fans of Jordan Peele, Jackal also comfortably rides the folk horror wave. Like Bethany C. Morrow’s Cherish, Farrah, Jackal also asks compelling questions about who society values as worthy of protection, and the true nature of monstrosity.

–Molly Odintz, CrimeReads Senior Editor

Lydia Millet, Dinosaurs

W.W. Norton, October 11

Millet’s latest novel, following her National Book Award-shortlisted A Children’s Bible, is a much subtler, sneakier affair, one that goes down easy but rattles around in your brain for weeks after reading. It concerns Gil, a man who became wildly wealthy as a teenager after the death of his parents, a fact that has led him to a life of philanthropy, volunteering, and for some reason, walking from Manhattan to Phoenix, where he buys a castle-like home in the suburbs, next to a house with one full wall made of glass. (Yes, it’s a Millet novel—our reality, but perhaps turned up a notch or two.)

Once there, he becomes deeply invested in the birds in his new home, as well as his neighbors, whose lives are revealed to him through the glass. Spoiler alert: that’s basically it. There’s no apocalypse. Things happen, a few of them wrenching, but this is a quiet, elegant novel, much more interested in wondering how a person—this person—should live, and watching how he does. More men like Gil, please, and more novels like this.

–Emily Temple, Managing Editor

Cormac McCarthy, The Passenger

Knopf, October 25

I have not yet read The Passenger, but I will confess that I love even the worst of Cormac McCarthy (I can understand why some people take issue with aspects of the Border Trilogy, but it’s still great to me). Apologies for quoting press copy, but this is exactly what I want to be reading as the days grow short and the nights get cold:

Traversing the American South, from the garrulous barrooms of New Orleans to an abandoned oil rig off the Florida coast, The Passenger is a breathtaking novel of morality and science, the legacy of sin, and the madness that is human consciousness.

Oh, the protagonist’s name is Bobby Winter.

–Jonny Diamond, Editor in Chief

Claire Keegan, Foster

Grove Press, November 1

Claire Keegan has written four brief, nigh-on perfect books over the last 23 years. Her career began with a pair of short story collections—Antarctica (1999) and Walk the Blue Fields (2007)—that all at once announced her as one of the greatest practitioners of the short prose form at which Irish writers historically have excelled and as the heir both to the unapologetic causticity of an Anne Enright and the Christ-its-beautiful-but-grim-in-the-Irish-countryside lyricism of a John McGahern.

After that followed two novellas, Foster (2010) and Small Things Like These (2021), the first of which began as a short story that won the Davy Byrne’s Irish Writing prize in 2009, then became a somewhat longer story in The New Yorker the following year, before appearing as a standalone volume. In many respects, Foster, now published by Grove, is a simple story.

It follows a young girl sent away while her mother is pregnant to live with some family friends, from whom she begins to receive the love and care she has been lacking and for whom she begins to fill the absence opened by the loss of their own child.

The book, though, is elevated far above the humility of its plot and structure by the sheer brilliance of Keegan’s writing—which is to say, by her bottomless empathy for her characters, by her elegiac descriptions of the natural world, and, above all, by her total ability to inhabit the developing perspective of a child and bring the girl to life, while gripping the reader across a gulf of ironic distance with a tone and tenor that are compassionate and heartbreaking where a thousand lesser writers end up cheap and patronizing. It’s in the nature of literary journalism for critics to deem this kind of book “among the finest stories written in English,” as The Observer, duly, did. It’s a cliché and it’s almost always bullshit or at least hyperbole. But in this case, it’s absolutely true.

–Emily Firetog, Deputy Editor

Katherine Dunn, Toad

MCD, November 1

A previously unpublished Katherine Dunn novel?! Is it as wild and weird and wonderful as Geek Love? Of course it isn’t, dummy; nothing is as wild and weird and wonderful as Geek Love, but Toad—which Dunn, who died in 2016, wrote, and then locked away in a drawer, over 50 years ago—is still a buoyantly scabrous gem of a novel as well as a fascinating precursor to the Oregon author’s grotesque opus.

From the small-town hermitage she shares with a vase full of goldfish and a yellow garden toad, an emotionally battered Sally Gunnar looks back at the various regrets, failed romances, and general misadventures of her youth. There’s a beautiful but cruel poet lover who urinates on her stash of donuts, a badly maimed manager, an act of nude vandalism, and a spell in a psychiatric institution which yields a liberating weekly disability check. Most of Sally’s reminiscences, however, are of her college days, which were spent within an extremely ripe-spelling bubble of Reed College eccentrics. When it comes to posthumous releases, there are cynical cash-ins and there are unearthed gems. Toad belongs firmly in the latter category.

–Dan Sheehan, Book Marks Editor-in-Chief

Erica T. Wurth, White Horse

Flatiron, November 1

Erika T. Wurth’s White Horse is part horror novel, part detective story, as a haunted woman finds herself compelled to investigate her mother’s long-ago disappearance. Why did her mother leave her at two days old? Why did no one listen to her father when he suspected foul play? How many others have gone missing the exact same way? What is her mother trying to tell her through the visions she sees when she wears her mother’s powerful beaded bracelet? And what is the horrifying presence she’s accidentally conjured into this world, along with her mother’s ghost? White Horse, like the bar in the story it takes its title from, is gritty, haunting, understated, and beautiful. Erika T. Wurth is of Apache, Chickasaw, and Cherokee descent, and sets out to capture the urban Native experience while also doing justice to deeply rooted spiritual beliefs and practices.

–Molly Odintz, CrimeReads Senior Editor

Graeme Macrae Burnet, Case Study

Biblioasis, November 1

From moment to moment, there’s very little you can take for granted in this inventive novel by Graeme Macrae Burnet, whose literary sleight of hand in Case Study landed the book on the Booker longlist and makes it one of the most fascinating reads of this fall. The story begins with testimony from a woman who is convinced that London psychotherapist Collins Braithwaite has “killed” her sister Veronica, who was meeting with him regularly at the time she jumped off an overpass at the age of 26. From there, the focus is on the relationship between the young woman and Braithwaite as the two investigate questions about the boundaries of a self, responsibility, and the role of a therapist, interspersed with their personal histories and with plenty of humor throughout. Burnet’s uniquely compelling characters are worth your time and attention.

–Corinne Segal, Lit Hub senior editor

Lynn Steger Strong, Flight

Mariner Books, November 8

Lynn Steger Strong has a way with families. Her previous novels (Hold Still and Want) explore, among other things, the cruel and unusual way siblings, spouses, and mothers love—and hurt—each other. In her newest novel, she dives right into a complicated family story. There are a lot of characters and relationships to track, but it is one of the best depictions of a family that I’ve read in a long time. Three siblings—Henry, Kate, and Martin—bring their spouses and a handful of kids together to Henry and Alice’s house in upstate New York for the Christmas holiday, the first since their mother’s death and the first away from the matriarchal house in Florida (which also happens to be their inheritance).

It would be easy to label the story a domestic fiction—we track Kate, her relationships with her sisters-in-law, their petty jealousies, and their motherhood woes. But a family story, especially in Strong’s hands, is a story of class and work and systematic inequality (Alice’s role as a social worker and—semi-spoiler—her missing client bring the perfect propulsion to the latter part of the novel). The world outside of the home is so complicated and tangible that it would be a mistake to imagine this is just a story of parents and children. It is a story about how families shape our lives, even when we are away from them, and what happens when the natural order of the world is disrupted. And its description and understanding of grief is a beautiful reminder of the power of parental love.

–Emily Firetog, Deputy Editor

Kevin Wilson, Now Is Not the Time to Panic

Ecco, November 8

Kevin Wilson’s Nothing to See Here is one of those books that pops up on lists and Twitter threads almost as often as Where’d You Go Bernadette—at a certain point, why fight it? It’s just a good, tender, warm, funny book that’ll make you feel and make you laugh. Wilson has a gift, and he’s back with Now is Not the Time to Panic, a book that similarly dances the line between what it is to be a child, and what it is to be an adult: a true “coming of age” story.

We meet Frankie Budge when she’s 16, angsty and confused about what it is to be a person in the world. When she meets Zeke, another conflicted teen who’s just moved in with his grandmother, sparks fly, and they become romantic and creative partners teamed up against the town and society that doesn’t understand them. Zeke is an artist, and they decide to paper the town with posters bearing the enigmatic phrase The edge is a shantytown filled with gold seekers. We are fugitives, and the law is skinny with hunger for us—a project that sets up a series of consequences they could have never foreseen.

Decades later, Frankie (now Frances) is contacted by a journalist with questions about the incidents that played out surrounding those fateful posters, and the “Coalfield Panic” that ensued. Wilson’s stories manage to be unexpected, totally new, and yet gets to the heart of human experience in the most familiar way. Now is Not the Time to Panic is the perfect book for this “back to school” season, reminding us of what it is to be young, to find your people, and to learn for the first time the true power of art.

–Julia Hass, Contributing Editor

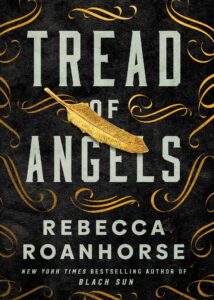

Rebecca Roanhorse, Tread of Angels

November 15

In this tough-as-nails novella, Rebecca Roanhorse imagines a late 19th century mining town with a most precious mineral for extraction, inhabited by the descendents of rebellious angels (known as the Fallen) yet exploited from above by those still accepted by heaven (known as the Virtues). Roanhorse plays with the notion of purity and original sin, as her townspeople must grapple with their permanently assigned “rebel” status and the seemingly virtuous come slumming at night to see the town’s most wicked delights.

A murder in town threatens to disrupt the fragile peace between Fallen and Virtues, and a demon girl must solve the crime or lose her sister forever to the punishments of heaven’s judgement. Rebecca Roanhorse is known for her incredible worldbuilding, diverse inspirations, and complex reinterpretations of tropes, and all her talents are perfectly on display in her latest. For those who can’t get enough of Roanhorse’s speculative fiction, check out Fevered Star, the sequel to her meso-American indigenous fantasy Black Sun.

–Molly Odintz, CrimeReads Senior Editor