2,000 Years Old and Still Going Strong: Aristotle’s Lessons in Storytelling

Philip Freeman on What We Can Learn From the Poetics

Of the many disciplines Aristotle developed, the study of literature as found in his Poetics is among the most engaging.

In spite of the title, the Poetics is about far more than poetry, at least in the modern sense of the word. In ancient Greece, almost all literature was written in poetic verse, from epic tales of heroes past to obscene comedies. Although Aristotle focuses primarily on tragedies such as Sophocles’s Oedipus Rex presented on the Athenian stage, his insights into storytelling are applicable to all kinds of modern literature, drama, and film.

But the Poetics suffers from being even less polished than most of Aristotle’s writings. It is full of logical gaps, missing pieces, and outright contradictions, not to mention a somewhat tedious section on linguistics and the loss of its entire second half, on the topic of comedy. We shouldn’t fault Aristotle for this but take the Poetics as we have it, as an inspired piece of work full of brilliant insights that was never meant to be published in its present form. If we do this, then we can begin to learn the many lessons the Poetics has to teach. A few of these:

All storytelling is a kind of imitation—Just as painters represent and interpret the world around them, writers tell of people, places, and things from real life in their stories. Even the most imaginative stories reflect the world as we know it; otherwise no one would be able to relate to them.

The most satisfying tragic stories are about good people who make mistakes.

Every story has an appropriate length—Even with a lengthy epic, the readers or viewers must be able to keep the whole of the story in their mind’s eye; otherwise they will become lost and lose interest. As Aristotle says, an animal too small to be seen or too gigantic to view at once is of little interest to us.

Stories must have a beginning, middle, and end—Although this may seem obvious, many stories fail terribly at being whole and complete. They often start strong but lose their way and end weakly or with an unbelievable event to bring the story clumsily to a close. A strong story, as Aristotle says, builds on itself, is consistent, and never loses its path.

Spectacle is secondary to story line—In a story presented on stage or screen, costumes, set design, and elaborate pageantry are all subordinate to the story itself. Audiences will not be impressed by even the most spectacular special effects without a strong story underlying them.

Plot is more important than characters— Although some writers and readers will disagree, Aristotle believes that the story itself comes before even the most interesting characters who inhabit it. Strong and well-developed characters are crucial, but the plot comes first.

The best conflict occurs between family and friends—Hostility and fights between strangers can be interesting, but for the most powerful and moving stories, make the conflict between people who love each other.

The Poetics is over two thousand years old, but it remains one of the most important handbooks for authors even today.

The most satisfying tragic stories are about good people who make mistakes—An evil character coming to a bad end is as predictable as a perfect character for whom everything turns out well in the finale. If you want to move your audience, make your starring role a basically decent person with a terrible weakness that ruins his or her life by the end of the story. Since we are all imperfect, we can identify with such people. Watching their downfall brings about pity for them and fear that such a thing could happen to us.

The Poetics is over two thousand years old, but it remains one of the most important handbooks for authors even today. Some of the best contemporary writers of stage and screen, such as Aaron Sorkin and David Mamet, think that this ancient Greek philosopher knew exactly how to tell a gripping story for any age. When it comes to writing “the rulebook is the Poetics of Aristotle,” Sorkin says. “All the rules are there.”

__________________________________

Excerpted from HOW TO TELL A STORY: An Ancient Guide to the Art of Storytelling for Writers and Readers © 2022 by Philip Freeman. Reprinted by permission of Princeton University Press.

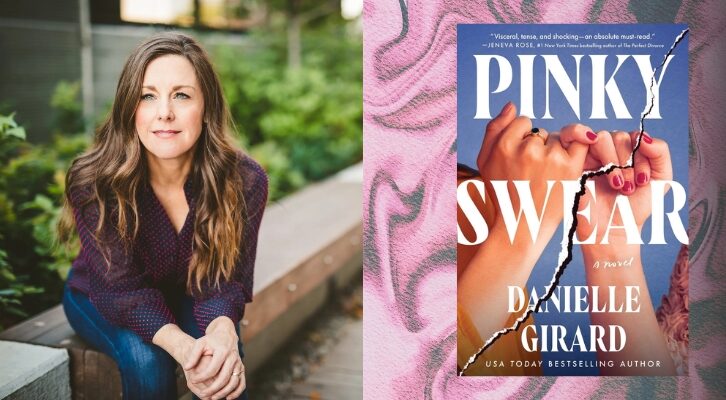

Philip Freeman

Philip Freeman is the author of more than twenty books on the ancient world, including the Cicero translations How to Think about God, How to Be a Friend, How to Grow Old, and How to Run a Country (all Princeton). He holds the Fletcher Jones Chair in Humanities at Pepperdine University.