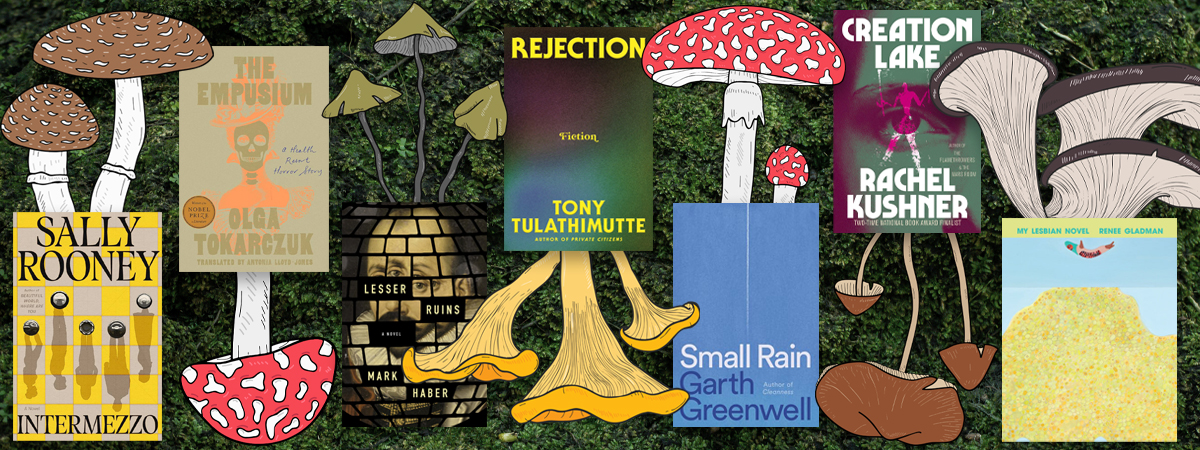

17 Novels You Need to Read This Fall

Reading Recommendations from the Lit Hub Staff

Have you noticed yellowing leaves, Labor Day sales, and the return of the school bus, now clanking spiritedly around your neighborhood? Congratulations, you’ve made it to another Big Book Season. There are a lot of books coming out this fall, and a lot of them will probably be very good, despite the election season of it all. Though we’re still working through our own fall piles, here are a few of the Literary Hub staff’s favorite new novels of the season.

Rachel Kushner, Creation Lake (Scribner, September 3)

Creation Lake is experiencing righteous hype for being several things at once. One the one hand, this novel is a slow-simmering thriller, featuring all the furniture from your favorite Bond flick or film noir. An American spy has been tasked to topple an eco-Marx-ish community in rural France. As Sadie, our droll protagonist, falls deeper in with the intentional community, suspense stems from wondering: will she have pity on her flawed but idealistic marks, or take the money and run?

Kushner pulls off the spy story with ease and wit. But because she is the rare novelist as deft with style as she is with ideas, Creation Lake is also operating as a canny, characteristically thoughtful engagement with the crisis of modernity. Our narrator is fine company, calibrated with just the right blend of snark and candor. But via slick, cheeky observations, Sadie’s mission somehow touches on the plight of rural farmers, intellectual theories of the French left, the heart and hypocrisy guiding radical movements, genetic predeterminism, and what the Neanderthals knew of utopia. And this isn’t even to touch on the gleefully rendered cast of bit players populating this under-examined corner of “the real Europe…a borderless network of supply and transport.”

This is a sharp, deep, dart of a book. I hated putting it down. –Brittany Allen, Staff Writer

Garth Greenwell, Small Rain (FSG, September 3)

I wasn’t sure I was going to be able to read this novel, because it depicts something that keeps me up at night: a life-threatening health crisis that appears suddenly, with no apparent cause, in an otherwise healthy person. (It’s boring to say that we are all subject to the randomness of our bodies, and yet.) But in the end it was not difficult to read this novel, Greenwell’s third. Not because it isn’t harrowing, in places, but because of the mind we are privy to in the course of it.

The book is both claustrophobic and almost impossibly expansive; we are sitting with the narrator in his hospital bed during the height of the pandemic, unable to move without help, veins blown out by constant IVs, but we are also sitting with the narrator in his head, following his thoughts as he considers poetry, desire, his family, the house and life he and his partner fought so hard for. It manages—sort of incredibly, ecstatically, if you think about it—to be utterly unsentimental despite technically being an illness narrative. It is also very moving. It is not any kind of drama that makes the love story at the center of the book—because what do you do in your hospital bed except consider the love story at the center of your life—but tenderness. Page-turning tenderness! That alone is a magic trick, though not the only one Greenwell pulls off here. –Emily Temple, Managing Editor

Danzy Senna, Colored Television (Riverhead, September 3)

Danzy Senna’s spent several books fathoming the psyches of identity-straddling Black folks. In her newest novel, Colored Television, she turns a gimlet eye on “mulattoes,” and troubles the tragic plot that has followed this moniker around for a century. When Jane, a writer with upper middle class aspirations (but adjunct income) fails to pull off the Great Mixed American Novel she’s promised her publisher, she pins her hopes on Hollywood. But turning her albatross into a punchy sitcom proves compromising, in more ways than one.

I can’t think of another book that so frankly depicts the conflict between longing for an artistic lifestyle and longing to make good art. We feel this in real time, as readers—as Jane’s desire for a certain kind of glossy respectability threatens to eat all that’s truthful in her life, her project itself grows diffuse. This clever, itchy-making, and often hilarious novel is unsparing on identity-driven fiction and creative working conditions under capitalism. Asking finally, what should suffer for our work: the truth, the hearth, or the spirit? –BA

Elizabeth Strout, Tell Me Everything (Random House, September 10)

Elizabeth Strout’s latest is a literary crossover episode, blending the universes of her beloved characters: Olive Kitteridge, Bob Burgess, and Lucy Barton all share the spotlight here, offering their idiosyncratic voices and poignancies. Each of Strout’s books has been a lesson in humanity and storytelling, revolving around the stories we tell ourselves or others in order to make meaning and understand our lives. These stalwart Strout characters each offer us something different in their resilience, quirks, and capacity for hope: Lucy with her childlike joy amid loneliness, Bob his practical forward momentum even through pain, Olive her acerbic but loving tendencies. The main plot of this novel is juicy: there’s been a murder in town and Bob takes the case in defending the main suspect, the son of the victim. This is its own intrigue, and keeps one turning the pages to find the answers, but that’s not really why we’re here. We’re here to live amongst these complicated, delightful characters as they traverse their lives and relationships, the reader just as embedded as they are in their day-to-days, their squabbles, their tender moments, all of it. In this gentle and moving book, life’s most powerful messages are distilled and delivered in sweet, simple prose. One never wants to leave this pure, exceptional universe that Strout has created. –Julia Hass, Contributing Editor

Sugiura Shigeru, tr. Ryan Holmberg, Ninja Sarutobi Sasuke (NYR Comics, September 10)

Cartoonist Sugiura Shigeru’s 1969 psychedelic, Pop Art take on the famous ninja Sarutobi Sasuke is a joy. Translated for the first time into English, Ninja Sarutobi Sasuke is a gallivanting and strange adventure, full of gags, magical run-ins, and trippy sequences as the titular ninja jumps around a historic Japan that seems to be fraying at its edges and picking up scrambled TV signals from all over the universe.

Shigeru’s writing follows a dreamy, magical logic, and Sarutobi’s adventures are a pastiche of older story-telling tropes and contemporary pop culture: cowboys, aliens, Hollywood stars, and song lyrics all swirl around the young ninja. The translation by Ryan Holmberg is inviting; for example, he updates some of the lyrics Shigeru included to be more legible, which leads to moments of surreal beauty, like an alien dancing while it sings “Baby Shark.” And the art is gorgeous; Shigeru is able to move between styles, sometimes within the same panel, in deliriously captivating ways.

Ninja Sarutobi Sasuke is part of a long Japanese tradition of the ninja as superhero, which Holmberg describes in his introduction. When Shigeru was a kid in the 1920s, there was even a “ninja boom” and moral panic, which sounds like an earlier version of the Jackass-fueled pearl-clutching of my youth: “…ninja-loving boys started jumping from roofs and breaking their legs and chanting spells in front of rushing trains.”

I don’t think this book will make you think you can leap buildings in a single bound, but Ninja Sarutobi Sasuke has an infectious, youthful excitement that brings together dozens of threads and influences into one funny and fascinating comic. –James Folta, Staff Writer

Renee Gladman, My Lesbian Novel (Dorothy, September 17)

I stumbled into Renee Gladman’s work while looking for fantasy cities I might want to visit as much as I do Ambergris or New Crobuzon. Someone suggested I check out Event Factory, the first in her Ravicka books, and I was immediately hooked. I think I read the four Ravicka books in the span of a week. Since then, every Gladman release is an event for me and I was particularly excited to see that her next book would be… a romance novel??? My Lesbian Novel is, of course, so much more than that—Gladman is too slippery a writer to be pinned down in any one genre or form—but it also very much is a romance novel in the spirit of the recent romance boom. The entire book is structured like one of those Paris Review “Art of Fiction” interviews, back and forth between an unnamed interlocutor and a writer named Renee Gladman who is working on (over the course of many years) a lesbian romance novel. The result is a fascinating exploration into the act of writing, into the passion we develop for “guilty” pleasures, into the rules and structures of genre fiction, and so much more. It’s also probably her most approachable work yet—a perfect introduction to all things Gladman, certain to hook a whole new swath of readers. –Drew Broussard, Podcasts Editor

Tony Tulathimutte, Rejection (William Morrow, September 17)

I’m not sure I’ve ever read a more gleefully merciless book than Tony Tulathimutte’s brilliant novel in stories. This is a book about, among other things, loneliness, the pitfalls and pratfalls of identity, ostracization, masturbation, the more deranged languages of the internet, toxic affirmation in the groupchat, and the many reasons you should never buy a corvid as a response to romantic rejection. (If that list doesn’t convince you to read it, I’m not sure our interests overlap.)

Tulathimutte is a connoisseur of the humiliating desires that lurk within all of us. Luckily, he’s also outrageously funny, and which makes it impossible to put the book down, even when the cringe threatens to annihilate you. I can think of no writer whose personal roasting I would fear more, but at least I know it would be extremely entertaining. –Jessie Gaynor, Senior Editor

Rumaan Alam, Entitlement (Riverhead, September 17)

Alam is always a seducer, and his latest novel is no different: it primarily concerns Brooke, a 33-year-old Black woman in New York, who lands a job assisting a billionaire who wants to give away his money. As so many in the novels of the upper crust, she slowly becomes untethered from reality, but the difference is, she doesn’t actually have any money. But it has deranged her anyway—just the idea of it, the proximity to it. Or maybe, more simply, the not having it. Or, well, having enough, but not everything, when everything is out there. But the seduction of the novel is really in the way Alam tells it, vividly and almost casually, deftly flitting from consciousness to consciousness; this is a book that whispers its secrets into the reader’s ear, a book that shows how strange our most normal desires can become. And hey, unlike an enormous Frankenthaler, you can probably afford it. –ET

Olga Tokarczuk, tr. Antonia Lloyd-Jones, The Empusium: A Health Resort Horror Story (Riverhead, September 24)

Olga Tokarczuk pastiche of Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain is a dark, feminist novel—atmospheric, creepy, and absolutely perfect. In 1913, Mieczysław Wojnicz goes to a sanatorium in the Silesian mountains to recover from tuberculosis. In the evening, the other men at the guesthouse gather, drink hallucinogenic local liqueur, and have vague, philosophical discussions—“Does man have a soul? Monarchy or democracy? Can one tell whether a text was written by a man or a woman? Are women responsible enough to be allowed voting rights?”—which are (surprise!) actually paraphrased misogynistic utterances from real famous men. Meanwhile, disturbing things are happening in the guesthouse and the surrounding hills: gathering spirits, dead bodies, femicide. I love Tokarczuk, but if Flights felt too expansive and The Books of Jacob too long, this Gothic horror is your way in. –Emily Firetog, Deputy Editor

Sally Rooney, Intermezzo (FSG, September 24)

The First Great Millennial Novelist has outdone herself with her latest novel. Well, she’s in her 30s now, like the rest of us. Intermezzo is a stylistic leap for Rooney, whose previous novels have a sort of immediate freshness that makes them feel, rightly or wrongly, cribbed from her own life. In this book, Rooney inhabits voices wholly unlike her own, shifting her prose style accordingly, as she tells the story of two brothers falling apart and coming together in the wake of their father’s death. It feels like a big family novel, and it is, even as it wonders what a modern family—what, not to put too fine a point on it, modern love—might look like. It is all wonderfully clever and convincing, a big meaty novel that you’ll feel compelled to speed through. –ET

Yuri Herrera, tr. Lisa Dillman, Season of the Swamp (Graywolf, October 1)

I was new to Yuri Herrera, and this flaneur’s fever dream of a novel kind of blew my hair back. A speculative account of the lost-to-history year the exiled revolutionary Benito Juaréz spent in New Orleans, this book is gloriously twisty. Even though you won’t find a word wasted. Low-hanging copy will describe New Orleans as the other main character; this is happily the case. But the dizzying, lawless swamp that excites a future leader’s political education is not rendered here in purple prose or broad strokes. Through Juaréz’s sharp, suspicious eyes, we see the beauty and the bloodshed. A stealthy resistance network weaves around the callow administrators of the slave trade. Moments of kindness and caretaking coexist beside and in spite of profound violence, illness, and pain.

Juaréz, who will go on to become the first indigenous president of Mexico, seeks and fails to find in this year a “simple, coherent, communicable story, something to put this chapter for his life in order.” Because the shifting ground of his refuge city resists narrativization. This one’s a compact, hectic, satisfying step through the looking glass. –BA

Kay Chronister, The Bog Wife (Catapult, October 1)

Chronister’s terrific second novel follows the Haddesley family, a band of West Virginia siblings whose lives revolve around the care of a bog that also provides them with, well, as the title says: a bog wife. The patriarch of the family is on his deathbed, the eldest daughter is on her way home to see him off, and things have not been going well in this household for some time… It’s Southern Gothic Shirley Jackson—the Haddesleys remind me of the Blackwoods from We Have Always Lived in the Castle but with more folk-horror eerieness around the edges. A decaying old house, generational family dramas, a wavering line between the real and the unreal… The Bog Wife is a spooky-season novel for folks who don’t (think they) like horror. –DB

Mark Haber, Lesser Ruins (Coffee House Press, October 8)

Lesser Ruins is Haber’s most ambitious novel yet, and possibly his best: a grief novel, yes, and an accumulation novel, yes, and an art novel—both a novel about art, and making art, or trying to, and a novel that is in itself a piece of art—in the sense that it works at you, pushes you around, changes you. (Not a given, these days.) In it, a man tries to write a book-length essay on Michel de Montaigne, but is distracted by thoughts of his wife, now dead after a long degenerative illness, his son, who can’t shut up about house music, his phone, which he cannot make stop beeping, his job teaching at the community college, from which he “retired” after his own rapid devolution, and his stint at a prestigious artists’ colony, where he also could not work. Instead of a book-length essay on Michel de Montaigne, our hero comes up with title after title for a book-length essay on Michel de Montaigne. Beware, writers, aspiring or otherwise: this book will be unpleasantly relatable. Also, you will love it. –ET

Luis Jaramillo, The Witches of El Paso (Atria/Primero Sueno Press, October 8)

Luis Jaramillo’s debut novel is a taut, fantastical, time-folding epic. The book traces several generations of the Montoyas, an El Paso family with deep roots and dormant powers. When young Nena implores God to “let me be brave and have adventures,” her prayers are answered literally. A nun strides through time and ferries her back to the past. On being conscripted to work in an ancient abbey, Nena starts to realize that the visions she’s suffered all her childhood are the stuff of brujas. And her magical powers will have lasting consequences for her descendants.

Scenes shift seamlessly between three eras: the eighteenth century abbey; mid-century El Paso, where Nena and her sisters struggle to stay afloat during wartime; and the present day, where Marta, a frazzled lawyer and Nena’s grand-niece, works to placate both her disenfranchised immigrant clients and her nonagenarian aunt. A second sight binds the women, and the consequential magic they tap into put me in mind of Practical Magic. As in that adventure tale, we start to suspect that the witches’ desires—for food, sex, freedom, and power—is the real sorcery. Jaramillo has a knack for writing lusty, restless spirits.

The scene setting in this one is also uncommonly rich. I carried images (and somehow, smells?!) from 1792 El Paso into my dreams. –BA

CJ Leede, American Rapture (Tor Nightfire, October 15)

Where to even start? I loved Leede’s debut, Maeve Fly, which just won the Splatterpunk Award—and while her skill with a kill is certainly on display in American Rapture, this novel is an entirely different creature. It is perfectly timed to this rage-filled season when theocratic repression is on the ballot and the minds of so many Americans, following a good Catholic girl named Sophie as she navigates the outbreak of a zombie-like plague that causes the infected to display violent sexual behavior before they expire. It is a pulse-pounding adventure story, certainly, but it is also an utterly brilliant story about deprogramming and the costs of emotional repression. A lot of comps are being thrown around for this book but for my money, it might be the best plague novel since The Stand. Yes, it’s that good—it will make you shake, it will make you cry, it will make you cheer. Hell, it might just make you think twice before you parrot any number of the cultural learnings you never questioned previously. –DB

Jeff VanderMeer, Absolution (FSG, October 22)

I am on record in these pages as a major VanderMeer fan—but I don’t think anything could have quite prepared me for the announcement that he’d be returning to Area X. The Southern Reach Trilogy was a brain-breaking reading experience for me that quite concretely changed me as a reader, as a writer, maybe even as a person—and part of the joy of that was how much Jeff left unanswered about Area X and the Southern Reach.What a wonder, then, that this new book manages to simultaneously answer some outstanding questions while not once diminishing the strangeness or unknowability of the original trilogy. It’s also some of Jeff’s best writing yet: flat-out hilarious at times (the f-bomb count in one section goes well into the triple digits) and also utterly unnerving at others. It is a demanding novel, to be sure, but my return to Area X left me newly changed—or changed again—or somehow re-changed. Let the lighthouse call you back and let the mad strangeness of that wilderness consume you once again. Not unlike David Lynch going back to Twin Peaks, Absolution is simultaneously unlike anything else VanderMeer has done and also perfectly in line with the works that came before it. –DB

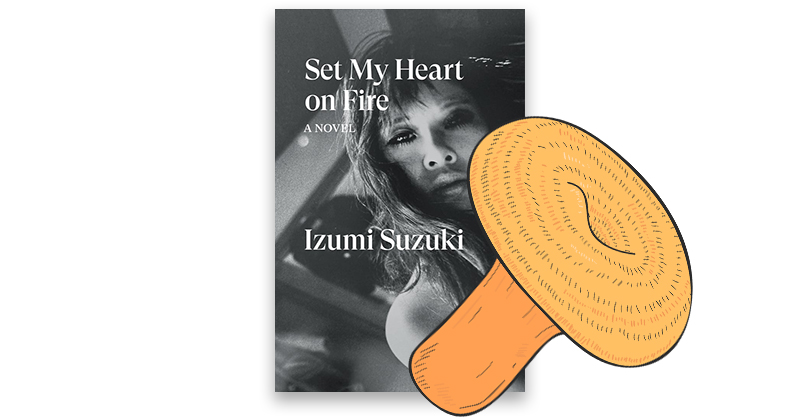

Izumi Suzuki, tr. Helen O’Horan, Set My Heart on Fire (Verso, November 12)

This is a novel about rock and roll and the obsession it inspires, set mostly in the quiet, late-night spaces where young people define their world through music. Suzuki’s characters idolize local bands, as well as the big ‘60s acts from the UK and America. They analyze and compare records, and situate their feelings in the mechanics of rock: “An echo-chamber pedal plugged into the night, the reverb coming back vividly enough to squeeze the blood from my heart.” Even their anger finds musical outlets — more than once someone throws out a stash of records in jealousy.

Set My Heart on Fire is a partial-growing-up story, about a young woman named Izumi who is aloof and aimless, but full of intense feelings and desires — she’s as cool and magnetic as the musicians she obsesses over, but not sure what to do with it. Her life takes abrupt turns following whims and social circumstances, and we’re never quite sure if any of this is what she wants.

This novel is short and engrossing, and a great addition and counterpoint to Suzuki’s short stories that Verso has already put out. While this novel doesn’t have any of the speculative sci-fi elements of her stories, Set My Heart on Fire has the same dreamy, almost dazed tone. While this book has all the grit, sex, and immediacy of rock, Suzuki’s plots and characters move with a lazy detachment: “Me, I decided once that I’d dedicate my life to rock music. But you don’t get much in return for doing that, so I gave it up.” It’s easier to put on a record, than to know what to do once it ends. –JF

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.