13 Ways of Looking at Denial: Jon Raymond on the Artistic Inspiration Behind His Novel

Part Four in the Series “13 Ways of Looking”

Jumping off Wallace Stevens’s classic poem, “13 Ways of Looking at a Blackbird,” 13 Ways of Looking asks authors to show the visual inspirations for their latest projects, with accompanying background on how these images directly or indirectly influenced their book. Fourth in the series is Jon Raymond, whose latest novel is called Denial.

–Rob Spillman

*

I wanted this to be an optical book. What does that mean, exactly? Well, for one, I wanted a lot of pretty things in there. I wanted interesting shadows on the walls, dappling sunlight on leaves, wavy images through marbled glass. I wanted all the pleasant little pictures that hit a person in their everyday life, and add a little luster to the monotony.

Denial takes place in the year 2052, after a Green New Deal has altered but not exactly transformed the world, and I was trying to imagine a future wherein human and animal life continues to exist and even, in ways, to thrive. That meant including the ongoing experience of visual beauty in the characters’ days. I can tell you: there were a lot of pretty clouds in the early drafts.

I wanted it to be optical in a more esoteric way, too. This idea came about gradually, and may never have manifested at all. The novel opens with a hologram of an eyeball (the main character is getting his eyes examined by some futuristic medical device), and culminates in an eclipse, and at some point along the way, as scenes added up, I noticed a lot of orbs and spheres appearing in the pages.

Moons, suns, ball sockets, that kind of stuff. It became one of those unexpected leitmotifs that can creep into a text if you’re paying really close attention, and this time, as the globular shapes proliferated, I started to think of the book itself as a kind of eyeball. I started trying to plane it into something round and polished and semi-transparent. I don’t know if that actually happened or not, probably not, but still, I continue to think of the book that way.

*

ROBERT ADAMS

The cover features an image by Robert Adams, a photographer whose pictures have guided my way of seeing for going on twenty-five years now. Like a lot of people, I first discovered Adams’ imagery in his body of work called The New West, from the 1970s, among the most beautiful pictures of the despoliation of the American West ever committed to photo stock (in my humble opinion).

My first novel, The Half-Life, is littered with descriptions drawn from Adams’ tract homes and vacant lots—a twisted hose here, a set of boards lying in the dust there. A screenplay I co-wrote called Wendy and Lucy (based on a story I wrote called “Train Choir”) pulled from his Summer Nights book in particular, and another script I wrote, Meek’s Cutoff, had Adams’s desert frames in its conception. I’m pretty sure Adams’ pictures crept into Kelly’s look book for Night Moves, too.

Adams currently lives in Astoria, Oregon, at the mouth of the Columbia River, where he’s been photographing clear cuts and other scenes of environmental degradation for quite some time. He also makes tranquil photographs of ocean water, and apples, and roadside grass.

In all his pictures, you feel his rigorous, sorrowful maturity at work, and his almost effortlessly classical sense of composition. I wanted to get some of that Adamsonian moral intelligence on the cover of this book, jarring against the title: Denial. In the novel, hopefully, the act of denial is presented as a moral quandary, possibly even an epistemology, of sorts. I was thinking about denial as a way of knowing, denial as a prerequisite for consciousness, even. I deny, therefore I am. That’s an idea that interests me, as none of my friends would find surprising at all. I like how Adams’ image of the Pacific Ocean bathed in sunlight offers a serene counterpoint to the alarming red text of the word.

*

THE ART OF MEXICO // CHARLES RAY

I started writing the book in the last month of 2019, on a trip to Mexico with my family and our friends Holly and Robin. I already knew my main character was going to travel down to Guadalajara (more on that momentarily), and thus I was collecting details of general Mexican urbanity for some of the street descriptions. Some details that made it in were this batch of hands outside a nail painting salon…

… and this bust from an awesome suite of sculptures of radio personalities in a park. I love that guy.

But probably the most incredible thing I saw on that trip was this sculpture in the anthropology museum depicting Coatlicue, Aztec mother of the moon and stars. In Aztec tradition, she’s a figure of destruction and creation, as you can probably tell by the terrifying aspect of this monumental block of carved stone. See how the two profiles of serpents combine to make a single humanoid face? And see the skirt made of coiling snakes? And those hands around her midriff are interposed with human hearts. God, what a mind-boggling object.

For whatever reason, the sculpture made me think of Charles Ray. As far as sheer craftsmanship and conceptual density goes, he seemed like the nearest contemporary analogue. In particular, I was thinking about his tree and his car crash sculptures, big, complex objects inviting long, multi-angular concentration.

It’s possible Ray was already in my mind, though, as he was already influencing the book in a very direct way. In this future world I was imagining, I wanted the characters to be reading novels. That was part of the optimism I was projecting, people still reading, and I think I’d already decided by then that I wanted the novel they read to be Huckleberry Finn. That book’s themes of friendship and disguise kind of feathered with my own themes, as I saw them, and the never-ending racial controversies pointed at a sadly permanent fixture of the American experience, even decades beyond our current times.

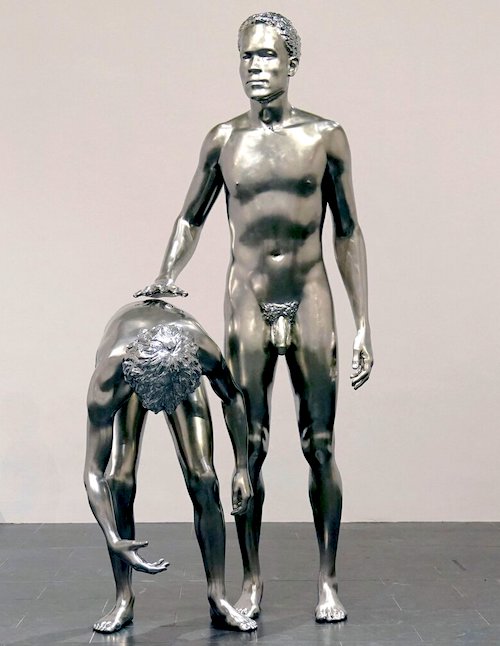

But most of all, I was thinking about Huckleberry Finn because of the sculpture by Charles Ray. Maybe you’ve seen it. It’s a stainless steel double portrait of Huck and Jim as nine foot tall nudes. It’s an incredibly simple but potent artwork, which is to say, a masterpiece, and operates by way of bringing the mythic figures into sudden, radically embodied relief.

Here they are: the pubescent white boy, Huck, and the middle-aged Black man, Jim, standing beside each other, naked, sterling. Huck is bending over while Jim is standing erect, his hand hovering over Huck’s back. What is it about this piece that made the Whitney de-install it in 2014? What is it about a naked Black man and white boy in close proximity that remains such hot potatoes?

I’ve thought about the book differently ever since seeing images of the sculpture. How often does that happen, a sculpture changing how you read? I wanted my characters to be reading Huckleberry Finn in the spirit of Charles Ray. I wanted my two characters to talk about Huck and Jim and grapple with the longevity of Twain’s text in the American imagination. Happily, the sculpture recently showed up at the Met where I finally got to see it in person. So yeah, if anyone out there is interested in making a new film adaptation of Huckleberry Finn, I stand ready to help.

*

LBJ // GEORGE W. BUSH

As an aside: the Huckleberry Finn conversation in my book happens between two characters who are in disguise. One is a journalist named Jack, the other is a fugitive named Robert Cave, a carbon criminal convicted of “Crimes against Life” and living underground in Mexico. In the book, I wanted this carbon criminal, Cave, to come across as a personable and even charismatic fellow. Otherwise, who cares if he’s unmasked and arrested or not?

To that end, I made him a Sunday painter in the style of war criminals like LBJ and George W. Bush. Isn’t it weird how both of those Texans went on to become painters in their retirements? And isn’t it even more bizarre, in the case of Bush, that his influences are actually pretty interesting? Alice Neel, David Hockney, Lucian Freud: Who was this guy’s art teacher, anyway? If I saw one of W’s pictures in a thrift store, I’d definitely think about buying it. I often think: if only he’d gotten in touch with his muse earlier, maybe a lot of death could’ve been averted.

*

JOSÉ CLEMENTE OROZCO

By far the biggest visual art influence on the book, however, is the work of Jose Clemente Orozco. For those who don’t know Orozco, he was one of the big three muralists of Mexico, alongside Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros. Among them, Orozco was by far the darkest, the least uplifting; ergo, my favorite.

I saw Orozco’s work for the first time when I was 18 and it was one of those signal encounters that you don’t realize is important but ends up being a big deal for the rest of your life. I was driving around Mexico with my friend Josh at the time. This was 1989, and we were taking what they now call a gap year, but we didn’t have that terminology then. We were just out on the road, seeing what we’d find. We’d made it as far as Guadalajara in our van and decided to stop and look at some art.

Probably it was a guide book that led us to the Hospicio Cabanas. It’s a Unesco World Heritage site, founded by the Spanish in 1791 as an orphanage and poorhouse. In 1937, Orozco was commissioned to paint the interior of the compound’s chapel, in a kind of Michelangelo-type job. Fifty-odd years later, I walked into the Hospicio and found myself inside a flaming collage of anti-fascist, anti-communist, anti-imperialist, anti-capitalist, anti-human, basically, carnage.

The images are all of war and colonial violence, stretching from pre-Columbian Mexican civilization to the wars of Orozco’s mid-20th-century moment. I wasn’t sure entirely what I was seeing, but understood I was in the presence of something conceptually very tough.

Let me set the intellectual stage a tiny bit more. At the time, I was reading Joseph Campbell’s Hero With a Thousand Faces, which was popular in those days, with its structuralist, ethnographic idea that the lives of modern men (very man-oriented, Campbell) were undergirded by some primeval story-pattern. In all cultures, Campbell claimed, this story repeated, a rounded path from innocence to experience, passing through initiation rites that echoed each other in strange ways. He was a slightly more intellectual version of a lot of men’s movement literature, more or less, adjacent to Carl Jung, sympathetic to Robert Bly.

In retrospect, it’s interesting to realize how much this archetypal thinking was percolating in the greater 80s. Maybe it germinated with Apocalypse Now, and its whole Golden Bough trip, and from there moved on to the Santeria fixation of the East Village, and the burgeoning urban primitive revival. It showed up in Denis Johnson’s Fiskadoro. Maybe it ended with the cover to Jane’s Addiction’s Nothing’s Shocking. Are you following? Or is this just my own connections I’m drawing? I’m trying to trace this fascination with a “savage” mythopoetics underlying the sanitized day to day in American life. Anyway, being a hip kid, I was trying to feel my way in.

Well, Orozco ended my interest in Joseph Campbell. Craning my neck at those murals, I saw no hero’s quest, no heroes, period. There was no quest at all, in fact, because there wasn’t a beginning or end, nor a center that was holding or not holding, as the case may be. What I saw instead was a mutating scene of violence flowing from one historical epoch to the next, and blanket oppression in German, Toltec, Russian, and Spanish costumes.

This was not the nearly Christian Rivera, with his pre-Columbian garden of Eden, nor the ultra-partisan Siqueiras, not that I knew much of them at the time. Orozco’s world was steeped in guilt, unrelentingly cruel. Why did his vision resonate with me so much? Me, a child of the suburbs, privileged beyond belief, possibly the most privileged person in the history of humankind? Why did I respond to Orozco’s nightmare Marxism so deeply? Why do I still?

Over the years, I’ve never stopped thinking about Orozco’s murals. They’ve become like wallpaper in my mind. Whenever I come in contact with a new idea, especially any political idea, I hold it up to the Orozco inside of me and judge it as true or untrue. Orozco has been my compass in that way, my tutor. In the new book, I send my characters—the reporter and the climate criminal—to Orozco’s frescoes and make them deal with his vision. They look and talk for hours in there. I ended up having to cut a lot of it. It could’ve gone on forever.

Jon Raymond

Jon Raymond is the author of five works of fiction, including the Oregon Book Award–winning story collection Livability and the Oregon Book Award–nominated novel Denial. As a screenwriter, he has collaborated on numerous films with the director Kelly Reichardt, including Old Joy, Wendy and Lucy, and First Cow. He also received an Emmy Award nomination for his screenwriting on the HBO miniseries Mildred Pierce directed by Todd Haynes and starring Kate Winslet. He was the editor of Plazm Magazine, associate and contributing editor at Tin House magazine, and a member of the Board of Directors at Literary Arts. His writing has appeared in Zoetrope, Playboy, Tin House, The Village Voice, Artforum, Bookforum, and many other places. He lives in Portland, Oregon.