13 Books You Should Read This February

Recommended Reading from Lit Hub Contributors

Sophia Shalmiyev, Mother Winter

Sophia Shalmiyev, Mother Winter

(Simon & Schuster)

Any book that came with glowing blurbs by Eileen Myles, Chris Kraus, Michelle Tea and Melissa Febos would have me rushing to the page, and as I am reading it, this memoir’s energy does remind me of why I love all those authors. Mother Winter is lyrical (an over-used adjective but apt here) and gutsy, delicate and meaty at once. Opening with “Russian sentences begin backward,” Shalmiyev re-traces the story of her childhood in 1980s Leningrad, her abrupt migration to America at 11 and her search, as an adult, for her estranged alcoholic mother. She weaves together memoir and meditations on language, her own motherhood, and the writers and artists that she worshiped as her “feminist mothers” in place of the real thing.

–Marta Bausells, European editor at large

Esmé Weijun Wang, The Collected Schizophrenias: Essays

Esmé Weijun Wang, The Collected Schizophrenias: Essays

(Graywolf Press)

The Collected Schizophrenias is a beautifully-written collection of essays by Esmé Weijun Wang. From diagnosis to daily life, she explores the schizophrenias from all angles. In one essay, she ruminates on the idea of motherhood and responsibility. In another, she brilliantly dissects the language around mental health. At once informative (she incorporates a bit about journalistic exposes on the mental health industry) and personal (she goes back through her family tree and doesn’t shy away from the schizophrenias’ effects on her personal relationships), this collection of essays tackles a stigmatized topic and gives us a portrait of an honest, bold writer who I’m excited to read more from.

–Katie Yee, Book Marks assistant editor

LeAnne Howe, Savage Conversations

LeAnne Howe, Savage Conversations

(Coffee House Press)

Savage Conversations features only three characters: Mary Todd Lincoln, Savage Indian, and The Rope. A play/poem/novel/historical nightmare, Howe mixes disparate textual, visual, and genre techniques to create something absolutely singular and haunting. This is a rare Lincoln cultural item that looks on the family with more vicious and complex emotions than nostalgia. It considers the largest “legal” mass execution in U.S. history. It considers the three dead Lincoln children, possibly killed by their own mother. It is set during Mary Todd Lincoln’s time in Bellevue Place Sanitarium and she is in a state of terrified ecstasy.

–Nate McNamara, Lit Hub contributor

Janet Malcolm, Nobody’s Looking at You: Essays

Janet Malcolm, Nobody’s Looking at You: Essays

(Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

What kind of sorcery is this? In eighteen narrative nonfiction pieces, Malcolm manages to pin down elusive clothing guru Eileen Fisher (and the fashion industry) and the three elegant sisters of Argosy bookshop in the Upper East Side (and the bookselling industry) alongside critiques of Tolstoy, email, Sarah Palin, sexual harassment, and Australian author and journalist, Helen Garner. Malcolm is a witty maestro of nonfiction, a wizard at using simple sentences to convey sharp and complex observations, and a doyenne at surprising us with stories that stretch beyond boundaries of the containers that hold them.

–Kerri Arsenault, Lit Hub contributor

Don Winslow, The Border

Don Winslow, The Border

(William Morrow & Company)

What’s the most urgent political issue of our times? It’s the action at the border, the flow of heroin into the U.S. from Mexico which is part of the opioid crisis that’s decimated a generation and provided a steady flow of immigrants from Central America and Mexico into the U.S. Reading Don Winslow makes me feel sad for people who think they are too good for genre fiction. They’ll never know how intensely pleasurable it is to immerse yourself in Winslow’s cartel trilogy (The Border follows The Year of the Dog and The Cartel), or to marvel at Winslow’s fine-grained rendering of the so-called war on drugs on both sides of the U.S.-Mexican border. It’s world-building of the highest order, dazzling in its detail, its plotting, and its politics. Winslow’s crime novel—and in its deepest heart The Border is an elaborate and humanistic crime novel—is uncannily topical.

–Lisa Levy, Lit Hub contributing editor

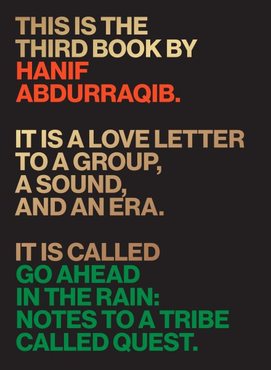

Hanif Abdurraqib, Go Ahead in the Rain

(University of Texas)

Hanif Abdurraqib’s essay collection They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us was basically the Platonic ideal of a book of essays rooted in various forms of art, in that it used a host of musical experiences—from specific songs to the experience of being in a crowded Midwestern emo show—to explore larger facets of contemporary American life. His latest work of nonfiction narrows the focus to one specific artist, but what an artist it is: Go Ahead in the Rain: Notes to A Tribe Called Quest is the title, and the book promises to be a stunning blend of author and subject.

–Tobias Carroll, Lit Hub contributor

Tara Conklin, The Last Romantics

Tara Conklin, The Last Romantics

(William Morrow & Company)

In 2079, oceans are rising, megastorms are commonplace, and power outages frequently sweep through New York City. Amid such chaos, a 102 year old poet named Fiona Skinner tells an auditorium full of admirers her family story: how she grew up with a depressed mother, formed tight bonds with her siblings, and weathered a family crisis as an adult that stretched those sibling ties to their limits. Tara Conklin’s The Last Romantics is a transporting epic touched with intimacy and tenderness. An elegantly crafted novel reminiscent of Ann Patchett’s Commonwealth.

–Amy Brady, Lit Hub contributor

Sandra Newman, The Heavens

Sandra Newman, The Heavens

(Grove Press)

When you first begin reading this novel, you think it’s set in the near-present, a year 2000 that we all lived. But it isn’t, quite. And soon you may think it’s a love story, a pretty one, between a boy and a girl obsessed with her own dreams. But that isn’t quite right either, though there is much beauty in this book, because soon the world begins to change. Weird and elastic and just barely apocalyptic, this is a novel that made me think for weeks; read it.

–Emily Temple, Lit Hub senior editor

Toni Morrison, The Source of Self-Regard: Selected Essays, Speeches, and Meditations

Toni Morrison, The Source of Self-Regard: Selected Essays, Speeches, and Meditations

(Knopf)

I had an opportunity to read a couple of selections from Toni Morrison’s new collection of essays, speeches and musings, The Source of Self-Regard. In one, the author offers a brief, moving reflection on Martin Luther King, Jr.’s legacy. Here I’m paraphrasing Morrison’s question to herself: Have I lived in such a way that Dr. King would have been proud of me? Though I have my own answer to that—it most certainly seems so, Ms. Morrison—her response is as concise, humble and surprising as one ought to expect from an author who has lately been giving us tiny gems (before this there was The Origin of Others, Morrison’s meditation on race and interpersonal borders). I will continue to take whatever it is Toni Morrison sees fit to give. This will be a welcome flame for any February ice storm.

–Aaron Robertson, Lit Hub assistant editor

Valeria Luiselli, Lost Children Archive

Valeria Luiselli, Lost Children Archive

(Knopf)

Luiselli writes like a poet. An intelligent and patient writer, Luiselli’s telling of this historical moment of walls and inhumanity breaks open the mystery that surrounds immigration making visceral a reality that few regard when thinking about the lives of the children involved. She is ethnographer and activist, a Meridel Le Sueur (I Hear Men Talking) and Alexandra Kollontai (Love of Worker Bees) fictionalizing political work as she is immersed in it. Landscapes and echoes dominate. Parallel narratives of Native American genocide and the as yet unnamed maltreatment of immigrant children cannot be ignored. That children hear, absorb, assume identities from story, worry, recognize dissonance makes this a most heartbreaking book.

–Lucy Kogler, Lit Hub contributor

Ausma Khan, A Deadly Divide

Ausma Khan, A Deadly Divide

(Minotaur Books)

Ausma Zehanat Khan’s Community Policing series has taken its politically astute Canadian detectives to Syria, Greece, and Iran in recent volumes, exploring a panoply of social ills through the wide-open eyes of Khan’s clear-sighted protagonists, ready to witness and act to preserve both human rights and human dignity. Her latest has her detectives Esa Khattack and Rachel Getty returning home to Canada to investigate the bombing of a mosque in Quebec amidst rising Quebecois nationalist sentiment and growing prejudice against Muslims nationwide. A Deadly Divide feels like a homecoming, but to a home that’s no longer a safe space. I can’t recommend this timely and urgent read enough.

–Molly Odintz, CrimeReads associate editor

Lauren Wilkinson, American Spy

Lauren Wilkinson, American Spy

(Minotaur Books)

If there was any justice in the literary world, any reader looking for a new spy novel would get a live drop of Lauren Wilkinson’s debut, American Spy, which brings a whole new warmth and realism to the form. The book’s African-American hero Marie is the daughter of a cop, an FBI agent stuck in the sexist bureaucracy of a New York field office, and little sister to a spy who died under mysterious circumstances. Telling her story to her twin children in the wake of an assassination attempt on her life, Marie leads us down a jittery path into the African theatre of the cold war in the late 1980s, when the CIA wants to set a honey trap for the charismatic new leader of Burkina Faso. Marie wants to do well by her work, but likes the man and also feels equivocal about what it is she’s supposed to undercut. This is an immensely poised feat of complex storytelling. Part love story, part family drama, all parts meditation on American foreign policy and the broken promises of our domestic sphere, it announces a major new voice in American fiction. Wilkinson is the kind of writer who remakes a form naturally and in so doing, conveys some infrequently seen truths about how our world operates.

–John Freeman, Lit Hub executive editor

C. D. Wright, Casting Deep Shade

C. D. Wright, Casting Deep Shade

(Copper Canyon Press)

C. D. Wright’s final book is a meandering and sinuous meditation on “beech consciousness.” Composed of fragments of poetry, natural history, folklore, and more, the book stands as a fitting crown to Wright’s body of work. At times reminiscent of Eliot Weinberger’s collage essays, Casting Deep Shade is a beautifully patterned thing, where light and shadow mingle.

–Stephen Sparks, Lit Hub contributing editor