10 Successful Writers Who Dropped Out (or Were Kicked Out) of School

In Case You're Already Getting Antsy

For some of you, school is officially in full swing. The newness has worn off a bit, and the dreaded homework has set in. Perhaps you’re already tired of it all. Officially, I am here to tell you: stay in school. School is worthwhile and our dismal public education system is what is going to destroy/has already destroyed this country. But it’s true that there are lots of notable visionaries, literary and otherwise, who dropped out of school—or were kicked out—for one reason or another. You probably already know about some of these: Mark Twain, Jack Kerouac, Jack London, William Faulkner, Harper Lee, F. Scott Fitzgerald, etc. But things are a bit different now, so I’ve tried to keep this list a bit closer to contemporary. Below, a list of successful writers who quit school, took a break, got expelled, and became intellectual superstars anyway.

Shirley Jackson

Shirley Jackson

Jackson matriculated at the University of Rochester (here is her pretty cute student ID card), and would have been part of the class of 1938 had she not dropped out after her sophomore year. Or, I suppose “dropped out” isn’t exactly the right term—her grades were so bad that year that at the end of it she was asked to leave. In her biography of Jackson, Ruth Franklin notes that the writer later commented that she had been kicked out “because I refused to go to any classes because I hated them.” She spent the next year writing, forcing herself to produce at least a thousand words a day, and when she applied to Syracuse University she did so with the goal of making writing her career. She matriculated there in September 1937, quickly found her feet, began publishing her work, and graduated in 1940.

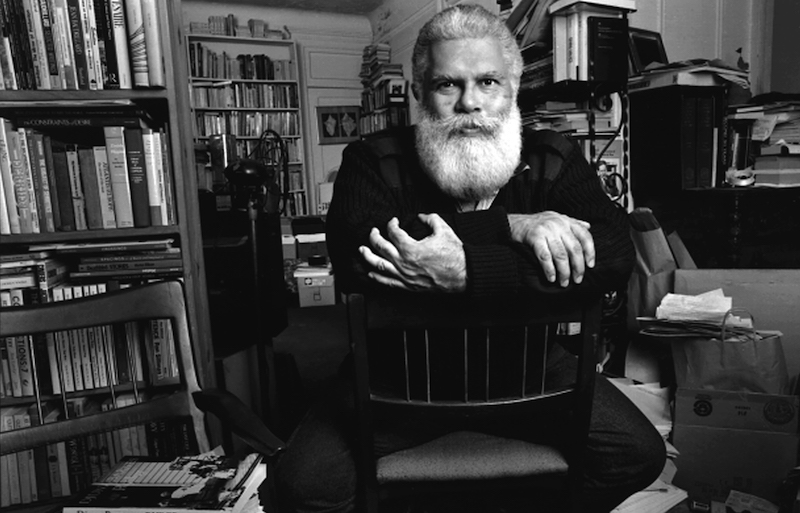

Samuel R. Delaney

Samuel R. Delaney

One of our best living SF writers dropped out of City college after only a semester—though he came back with vigor to the academic world as a professor, teaching at several great schools including the University of Massachusetts Amherst, Cornell, and Temple University. When an interviewer asked him in 2011 why he’d dropped out, Delany said: “I wasn’t smart enough.” But of course that isn’t true, considering he’s a brilliant writer, and so he continued:

By that I mean I lacked a particular kind of organizational discipline or intelligence. I had the reading under my belt. I had the analytical chops. I was a magpie for picking up facts and dates. But to do well at college—there’s no way around it—you have to be able to organize your time, which I could not do to save myself. I’d get started on one thing, and twenty minutes later I’d be off on another, in the midst of which I’d pick up some book on calculus or archaeology or Galois theory and read the odd hundred pages about that. I was intellectually all over the place. I was writing music, directing plays, acting in them, singing in folk groups, choreographing dances, and if I had a paper due next week, there was at most a one-out-of-five chance I would finish it—some of which, yes, was the bad side of Dalton, because they’d been fairly accepting of that sort of thing and had often been willing to cut me some slack. But I didn’t have the discipline. Still, not once did I ever think, Hey, I’m superior to all of this! I never thought, I know more than these people. When I flunked out, I flunked out miserably, spectacularly, and I was mortified. I thought, The truth is out, I’m an idiot. Now everyone knows.

It took me a while to realize that if a teacher had taken me aside and said, “Come on, Chip, sit down, let’s talk, this is how you have to do this,” probably I would have learned how to negotiate it. But nobody did.

Once he’d become a comparative literature professor, Delany wrote an essay entitled “How to Do Well in This Class” and handed it out to his students. “Basically it’s about what’s gained by living your life in end-stopped time units, both for work and for play,” he said. “I wish I’d had it when I entered college.”

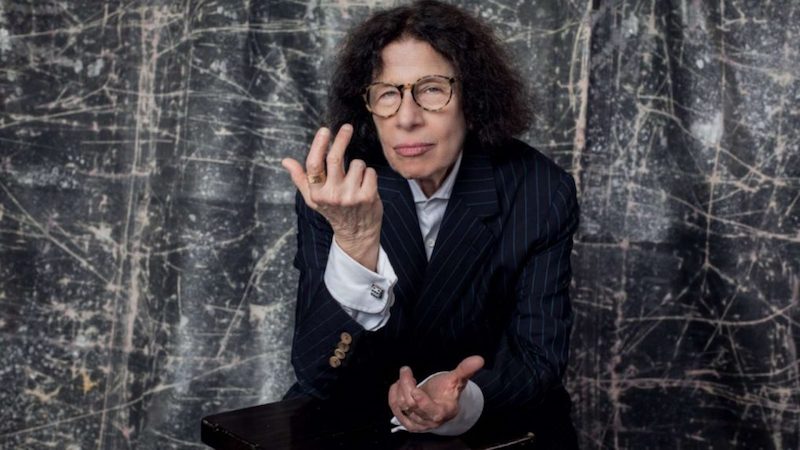

Fran Lebowitz

Fran Lebowitz

This one is my favorite: the hilarious Fran Lebowitz was a terrible student—that is, once she’d graduated from grammar school, “where the main requirement was drawing Pilgrims, which I was fantastic at.” In an interview with CBC Radio One, she said that one of the reasons she didn’t do her work in high school was because she was reading too much on her own, and she was often thrown out of the classroom for reading during lessons. “I would put a book I was reading behind my book . . . I was thrown out of class in grammar school numerous times because I was reading James Thurber, and you could not stop laughing. You cannot secretly read James Thurber.”

She was doing so badly in public school—getting report cards full Fs, sleeping in class (if not reading)—that her parents sent her to a private school “at tremendous financial sacrifice which was mentioned hourly.” It was an Episcopal girls’ school, and she didn’t last there very long. The headmaster expelled her in her senior year, telling her mother, “She’s a very bad influence on the other girls and she’s usurping my power.” In retrospect, she said, “I think I was thrown out of school for what my mother used to call that look on your face.” Perfect.

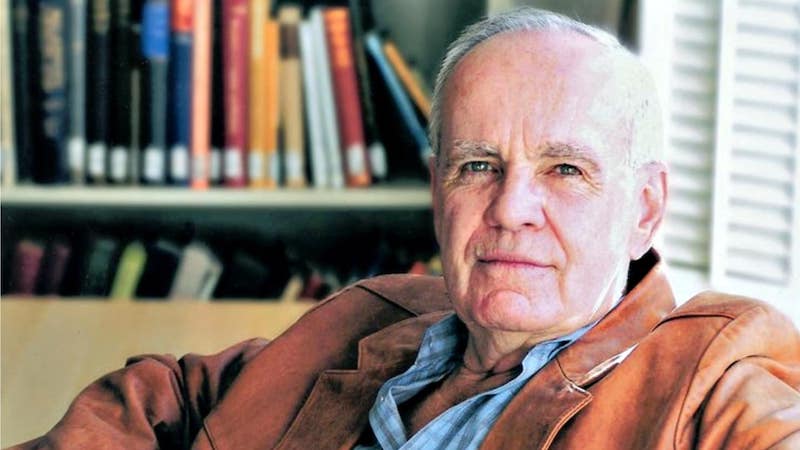

Cormac McCarthy

Cormac McCarthy

As you’ll know doubt know if you’ve ever read one of his novels, McCarthy doesn’t do things by halves—he’s more likely to do them double. So you may not be shocked to learn that he didn’t drop out of the University of Tennessee once, but twice. The first time was in 1953, to join the Air Force. He was discharged in 1957, and shortly thereafter re-enrolled, studying physics and engineering, before dropping out again after another two years, withdrawing in 1959. According to Willard P. Greenwood’s Reading Cormac McCarthy, it was during this second stint at college that McCarthy developed his distinctive punctuation style (read: very sparse punctuation). An English professor hired him to edit a book of eighteenth century essays, and in the process, McCarthy “developed his distaste for the semicolon and . . . came to the realization that punctuation is not essential to clear writing.” Well, I suppose he got something worthwhile out of college, even if he didn’t get a degree.

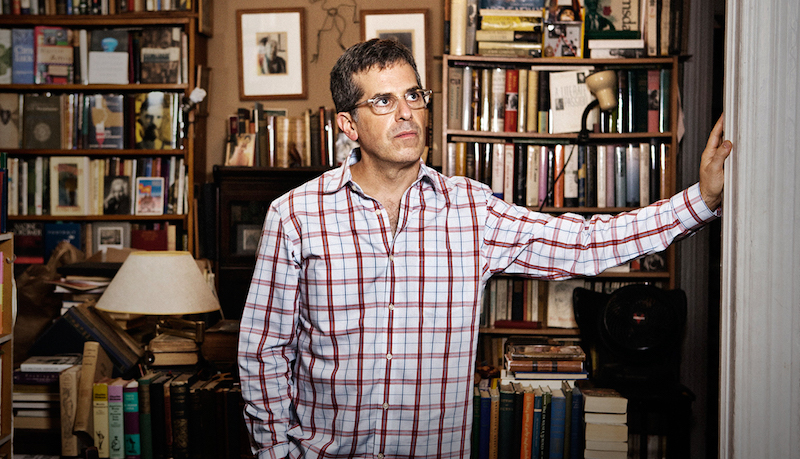

Jonathan Lethem

Jonathan Lethem

Jonathan Lethem might have been part of the Bret Easton Ellis/Donna Tartt/Jill Eisenstadt crew at Bennington—except for the fact that he didn’t stick around long enough. “I began dropping out of Bennington—rejecting it in a “you can’t fire me, I quit” sort of way—immediately upon arrival,” Lethem told The Paris Review.

It’s absolutely true that I was trying to prove something by running away to a world of privilege. I meant to prove I wasn’t deprived, and my reward was a violent confrontation with the realities of class. A confrontation I’d then spend ten years recovering from. I was frightened by my father’s bohemian idealism, and I was equally frightened by what I saw as the corruption of art by money and connections at Bennington.

He started writing his first novel and he decided he had to drop out to write it.

The school cost a then astronomical fourteen thousand dollars a year. I only wanted to work in bookstores and write fiction. I explained it to myself very logically at the time—I liked hanging out with my new friends and I hated going to class. Since I was paying to go to class, I dropped out. I was one of those creepy dropouts who moves into his girlfriend’s dorm room. She stole meals from the dining hall in a Tupperware container hidden in a hollowed-out textbook, and I sat in her room and wrote an unpublishably bad first novel.

That novel was Apes In The Plan, which Lethem describes as “a heedless attempt to splice J.P. Donleavy to Philip K. Dick and Devo (whose song, Jocko Homo, was the source of the title). I wrestled with this manuscript for more than three years, an effort that superseded my career as a college student, becoming an autodidact’s (or drop-out’s) self-assigned thesis work.” He started it just before turning 19. He wouldn’t begin Gun, with Occasional Music, his first novel, until he was 24, and it wouldn’t be published until he was 30.

Doris Lessing

Doris Lessing

Nobel Laureate Doris Lessing barely even started high school: she attended an all-girls Roman Catholic convent school in what is now Harare. She hated it, and eventually was allowed to come home at age thirteen—only to be sent away again to a boarding school. It was better, but she still hated it, and after coming down with a debilitating case of pinkeye, she refused to go on with her education. At the age of fourteen, she quit forever. In The Golden Notebook, she wrote:

Ideally, what should be said to every child, repeatedly, throughout his or her school life is something like this: ‘You are in the process of being indoctrinated. We have not yet evolved a system of education that is not a system of indoctrination. We are sorry, but it is the best we can do. What you are being taught here is an amalgam of current prejudice and the choices of this particular culture. The slightest look at history will show how impermanent these must be. You are being taught by people who have been able to accommodate themselves to a regime of thought laid down by their predecessors. It is a self-perpetuating system. Those of you who are more robust and individual than others will be encouraged to leave and find ways of educating yourself—educating your own judgements. Those that stay must remember, always, and all the time, that they are being moulded and patterned to fit into the narrow and particular needs of this particular society.

More robust and individual indeed.

Jamaica Kincaid

Jamaica Kincaid

Kincaid is another writer who left school twice, though for very different reasons than McCarthy. As a child in Antigua she was educated in the British colonial school system, and was an excellent student, always at the top of her class, but when she was sixteen, her stepfather became too sick to work and her mother took her out of school so that she could help provide for the family. At 17, she was sent off to Scarsdale to become an au pair for a wealthy family. “I wasn’t quite a servant, but almost,” Kincaid said. The idea was that she would send money home, and go to night school to become a nurse, but Kincaid took her freedom and ran with it, not even opening her mother’s letters and eventually leaving her job. She studied photography at the New York School for Social Research, but soon moved to New Hampshire to attend Franconia College, because, she said, “I thought maybe I should go to college.” But dropped out after a year, this time to return to New York and become a writer—first writing features and interviewing celebrities for magazines, and later writing iconic fiction and literary nonfiction. Happy ending!

Jackie Collins

Jackie Collins

Mega-bestelling romance novelist Jackie Collins was trouble in school, and eventually her parents sent her to the all-girls Francis Holland School in Baker Street (school motto: “That Our Daughters May Be As The Polished Corners Of The Temple”). “I wasn’t like the other girls,” she said in a 2012 interview. “I had one friend a couple of years older than me who taught me everything I know. And the rest of them were just bloody idiots, stupid little girls.” She got in a lot of trouble—writing and selling dirty limericks and other erotic literature, for one thing, and smoking of course—but said she was finally expelled, at the age of 15, “for playing truant and for waving at the resident flasher and going, ‘Cold day today, isn’t it?’, which the school thought was disgusting.” In response, Collins threw her school uniform into the Thames. After that, her choices were to go to reform school or to join her sister in Hollywood. She chose the latter, had an affair with Marlon Brando and a brief acting career, but soon switched to writing. Her very first book, published in 1968, became a bestseller, and then every other book she wrote after that did too.

Lois Lowry

Lois Lowry

The future author of The Giver matriculated at Pembroke College in Brown University in 1954 but left after her sophomore year, at age 19, to get married to a U.S. Navy officer. “Women did that so often in those days,” she wrote. But she wasn’t done with her schooling. Four children, many moves and several years later, she managed to finish her degree—and then go on to graduate school. “My children grew up in Maine,” she wrote.” So did I. I returned to college at the University of Southern Maine, got my degree, went to graduate school, and finally began to write professionally, the thing I had dreamed of doing since those childhood years when I had endlessly scribbled stories and poems in notebooks.”

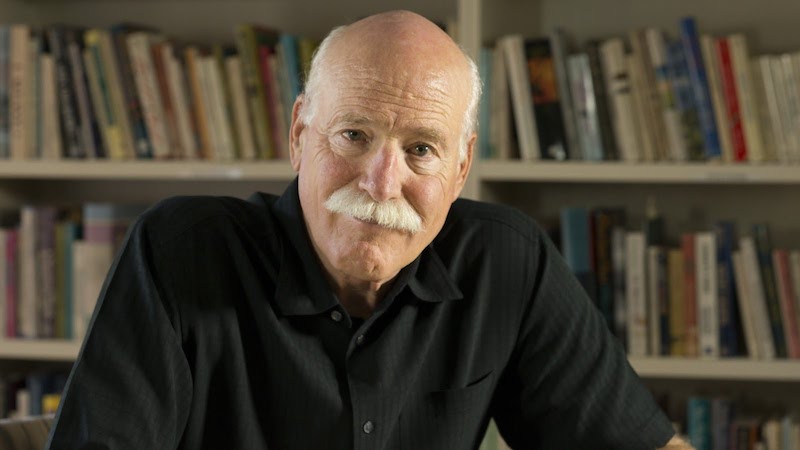

Tobias Wolff

Tobias Wolff

Tobias Wolff famously had to forge his own letters of recommendation to get into the Hill School, a private Pennsylvania boarding school. He did get in, but was later expelled for reasons including failing to get good grades, keeping an “untidy room” and “eating potato chips while leaning out the window”—though in 1990 the school granted him an honorary degree (’64) and in 2004 presented with the school’s “Sixth Form Leadership Award,” given annually to an exemplary role model for today’s students. In a 2003 interview, Wolff explained:

I was asked to leave in my last year not because of any misbehavior but because of my academic record. It was so abysmal that I lost my scholarship and of course couldn’t afford to go. I just couldn’t make myself study things I wasn’t interested in, and now I wish I had. Not that I regret the path my life has taken, but I can’t help my daughter with her math homework. It’s ridiculous. I simply couldn’t pass a math course while I was there. I’ll give myself this break—they were studying mathematics in a form that has since been completely abandoned.

But it was a felix culpa. It felt like a disaster to me at the time and I ended up enlisting and spending four years in the Army. But the truth is, I think I ended up having a much more interesting life because of that expulsion. I don’t regret it.

Obviously, the school does, at least a little bit. Fun fact: Wolff’s novel Old School is largely based on his experiences at the Hill School—and the photograph on the cover even shows the real dining hall.