10 shiny new books you should pick up this week.

Every week, the TBR pile grows a little bit more. It’s getting precarious. It’s taking up your whole nightstand. It’s threatening to crush you in your sleep. Well, what are you waiting for? Get cracking. What are you reading this week?

Colum McCann, Apeirogon

(Random House)

The latest novel from the National Book Award-winning author of Let the Great World Spin tells the story of two men, one Israeli and one Palestinian, both based on real people, both of whom lose their young daughters because of needless violence, and both of whom translate their grief into friendship and joint advocacy for peace. Told in short sections counting down from 500 to 1, and incorporating photographs and quotes from other thinkers, this novel might be McCann’s most ambitious yet.

–Emily Temple, Lit Hub senior editor

Walter Mosley, Trouble Is What I Do

(Mulholland Books)

While Mosley is best known for his Easy Rawlins series, I’ve always been partial to his Leonid McGill series, featuring a morally ambiguous protagonist who protects his family before all else, even as the various members of his extended clan drive him to distraction. Leonid’s new task is irresistible: he’s to inform a prominent white family of their many black relatives, upon the request of an elderly Mississippi bluesman.

–Molly Odintz, CrimeReads senior editor

Ken Liu, The Hidden Girl and Other Stories

(Gallery / Saga Press)

The Hidden Girl is Ken Liu’s first collection since his award-winning The Paper Menagerie and Other Stories was published in 2016. It compiles sixteen of Liu’s recent science fiction and fantasy stories, in addition to a short novel and an excerpt from The Veiled Throne, the third book in Liu’s Dandelion Dynasty Series. If this is anything like his previous work, fans can expect a diverse set of tales that infuse Liu’s often surrealist scenarios with sharp philosophical reflection.

–Aaron Robertson, Lit Hub assistant editor

Anne Carson, Norma Jean Baker of Troy

(New Directions)

Any new book from Anne Carson is reason for celebration. This hybrid work, originally staged as a play (of sorts) at the Shed, starring Ben Whishaw, examines the lives of Marilyn Monroe and Helen of Troy, only merged and transformed as only a poet and classicist of Anne Carson’s quality (and weirdness) would ever think to do. I’m here for whatever she wants to try.

–Emily Temple, Lit Hub senior editor

Monica Sok, A Nail the Evening Hangs On

(Copper Canyon Press)

How do you hold history if it’s not entirely your own? With your hands, your tongue? What to do when it’s being forgotten? To read Monica Sok’s debut collection, A Nail the Evening Hangs On, is to ask these enormous questions with her. Looking into the Cambodia she and her family has known, Sok conjures the dead and sings in their voices. Other poems adopt personas of the living. Traveling to Phnom Penh, Sok is respectful of the city’s ghosts, scolding tourists and classmates who tread war museums with heavy feet. In a world in which genocides, the likes of which Cambodia lived through are being forgotten, this is important work, as lived in as a face. Not at all abstract. Like Solmaz Sharif, who in “Look” made an elegy on behalf of elders, Sok honors hers here with the acute, protective tenderness of her gaze, the risks she takes in imagining her way into their lives. Let alone those of strangers. Sok shows them the ultimate respect by worrying over getting it right, knowing, in many cases, the past cannot always answer back. It is a mute loom. Beautifully, therefore, Sok praises the loom too.

–John Freeman, Lit Hub executive editor

Cathy Park Hong, Minor Feelings

(One World)

In this memoir in essays, the poetry editor of the New Republic (and the author of one of our favorite poetry collections of the decade) unpacks her experiences as an Asian American—and the “minor feelings” of shame, sadness, dysphoria, and more which it engenders—as well as the culture, not least the culture of whiteness, that surrounds her. An incisive book from one of our best poets and writers.

–Emily Temple, Lit Hub senior editor

Sierra Crane Murdoch, Yellow Bird

(Random House)

Under the auspices of empires and corporations alike, America has been built from murderous and unrelenting conquest: of land, of resources, of people, a war of extraction that continues to this day, at great human cost, in the Bakken oil fields of the Dakotas. Yellow Bird tells the story of Lissa Yellow Bird who returned to her home, the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation, to see it radically changed by the oil fields and the men and money they bring. But it is the disappearance of oil worker Kristopher “KC” Clarke from the reservation oil field that captures Yellow Bird’s attention, and forms the throughline of Sierra Crane Murdoch’s deeply reported story of greed, healing, and generational trauma.

–Jonny Diamond, Lit Hub editor in chief

Adam Cohen, Supreme Inequality

(Penguin Press)

I’m not saying you need to read more about the making of an unjust America, but Supreme Inequality is probably the next book to pick up if you are curious about the Supreme Court’s more conservative leanings over the past few decades. Bestselling author Adam Cohen puts the justices and their court cases over the last fifty years under the microscope in what Library Journal deems “a must-read.”

–Katie Yee, Book Marks assistant editor

Erik Larson, The Splendid and the Vile

(Crown)

When the King asked Winston Churchill to Buckingham Palace on the night of May the 10th 1940, the British Bulldog was not the most obvious choice to replace Neville Chamberlin. Although head of the Admiralty for the second period in war time, Churchill was 65 years old, he drank too much, and he was widely thought to be impulsive. While considered great at orating, he was not deemed reliable. Time would prove this wrong, as Larson’s phenomenal new book reminds in vivid detail as it chronicles Churchill during the Blitz.

Drawing on a forensic level of research, Larson recreates this much studied (and storied) time and brings it viscerally to life. This book is peppered with eye-popping details. Like how the Germans developed bombs which screamed as they fell, to further terrorize civilians. Or that the British public was told if parachuters started landing in their cities to destroy any maps at home and take the carburetor out of their cars to render them useless. Larson describes how for Mary Churchill the war only became real not when her father became PM, but when Cafe de Paris, one of the clubs she used to drink in, was shelled, killing band members and dancers in the middle of a party. One man torn right in half.

And yet the parties continued. As the bombs were dropping, Churchill’s son Randolph was on a ship heading to Egypt, gambling up debts equivalent to $190,000 today. He cabled home to his wife, Pamela, instructing her to pay ten quid at a time to the various shipmates—most of them very wealthy—to whom he’d lost. Pamela eventually sold her wedding presents, jewelry, rented their house out, and moved to London to get a job so she could pay off her husband’s debts.

London through this period was under war rations. At night the city was so black people walked into each other or into the street to be hit by cars. To his credit, Averhill Harriman, though the son of a railroad baron, new what to expect. When he flew to London to meet Churchill and begin coordinating diplomacy, he bought tangerines in Lisbon on his layover and gave them to Clementine Churchill, noticing her unfeigned gratitude.

Drunk and ambitious, approaching his seventh decade, Churchill waded through the conflict doing what he could best: persisting and being stubborn for one. Shortly after arriving, Harriman had dinner with Churchill and wound up spending a bombing raid night with the PM, as 100,000 incendiary canisters were dropped on London. They watched from the roof of No. 10 with metal helmets on. 200 fires were started instantly. Meantime, Churchill prepared the nation with speeches and talks and kept them up as the raids continued. Using that time’s technology to the limits of his reach, but not becoming a demagogue in the process. He wanted England to think of itself and to prepare. This is a deeply compelling work of history, and without resorting to heroism, it makes one long powerfully for real leadership.

–John Freeman, Lit Hub executive editor

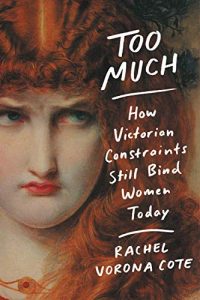

Rachel Vorona Cote, Too Much

(Grand Central Publishing)

Lit Hub contributor Rachel Vorona Cote blends cultural criticism and Victorian literature in a book that explains the ways in which all women are still susceptible to being called “too much,” exploring how culture grinds away our bodies, souls, and sexualities, forcing us into smaller lives than we desire. An erstwhile Victorian scholar, Cote sees parallels between the Victorian fixation on women’s “hysterical” behavior and our modern policing of the same. Too Much encourages women to reconsider the beauty—and power—of their excesses.

–Emily Firetog, Lit Hub deputy editor

Katie Yee

Katie Yee is a Brooklyn-based writer.