The Little-Known Friendships of Iconic Women Writers

Why Have They Been Mythologized as Solitary Eccentrics or Isolated Geniuses?

Literary friendships are the stuff of legend. The image of Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Wordsworth tramping the Lakeland Fells has long been entwined with their joint collection of groundbreaking poems. The tangled sexual escapades of the later Romantics Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley fueled gossip in their own time, and remain a source of endless fascination. By the mid-19th century, Charles Dickens was taking Wilkie Collins under his wing: publishing the younger writer’s stories, acting in his household theatricals, initiating excursions to bawdy music halls. And the memoirs of Ernest Hemingway offer readers a ringside view of his riotous drinking sprees with F. Scott Fitzgerald, thereby securing the pair’s Jazz Age friendship its place in literary lore.

But while these male duos have gone down in history, the world’s most celebrated female authors are mythologized as solitary eccentrics or isolated geniuses. The Jane Austen of popular imagination is a genteel spinster, modestly covering her manuscript with blotting paper when anyone enters the room. Charlotte Brontë is cast as one of three long-suffering sisters, scribbling away in a drafty parsonage on the edge of the windswept moors. George Eliot is remembered as an aloof intellectual who shunned conventional Victorian ladies. And Virginia Woolf haunts the collective memory as a depressive, loading her pockets with stones before stepping into the River Ouse.

Our own experiences, as writer friends, led us to question these accounts of extreme seclusion. Over our 16-year friendship, we have come to rely on each other: critiquing early drafts, passing on news of writing courses and contests, exchanging details of literary agents. As we trod our joint path, sharing moments of both celebration and consolation, we found ourselves wondering whether some of our favorite female authors of the past had enjoyed this kind of support.

The research we’d end up undertaking would offer us sustenance during our long years of striving to become published authors. This joint work would lead us—via bundles of letters yellowing with age, neglected wartime diaries, and personal mementos stored in temperature-controlled rooms—to a treasure-trove of hidden alliances.

“While these male duos have gone down in history, the world’s most celebrated female authors are mythologized as solitary eccentrics or isolated geniuses.”

We would make the surprise discovery that, in the early 19th century—the era of Wordsworth’s treks with Coleridge, and Byron’s adventures with Shelley—Jane Austen forged a rather more unlikely bond. Ignoring the raised eyebrows of her relatives, she befriended one of the family’s servants. Anne Sharp, the governess of Jane’s niece, penned household plays in between teaching lessons. Though separated by the mighty class divide, the pair’s shared status as amateur writers acted, for a time, as an important social leveler. Yet the differences in their circumstances always threatened to open a gulf between them. The audacity of these two intelligent single women, who built their relationship against the odds, upturns the well-worn version of Jane as a conservative maiden aunt, devoted above all else to kith and kin.

Sadly, although many references to her friend crop up in Jane’s correspondence, only one letter from her to Anne Sharp survives. However, we were able to catch glimpses of their creative collaboration in a rich variety of archival sources. Chief among these were the letters and unpublished diaries of Jane’s beloved niece, Fanny Knight (née Austen). One of the highlights of our research was the moment when we happened upon two documents that had been hidden in the pockets of young Fanny’s diaries for well over 200 years. These papers offer accounts of the all-but forgotten theatricals that Anne penned and put on in the household of Jane’s brother, shedding light on the writing of the unlikely friend to whom Jane turned for literary advice.

Like her predecessor Jane, Charlotte Brontё is rarely imagined outside her apparently narrow world—in her case, the Yorkshire village where she dwelt with her literary siblings. But we’d learn that she enjoyed a lively friendship with the pioneering feminist writer Mary Taylor, whom she had met at boarding school in 1831. From frictions during these early days, to daring adventures abroad as young women, to a shock announcement from Mary, these two weathered many storms. Their relationship paints a picture of two courageous individuals, groping to find a space for themselves in the rapidly changing Victorian world.

As in the case of Jane Austen and Anne Sharp, surviving correspondence between Charlotte and Mary is similarly limited. Frustratingly, in this case Mary was the one who destroyed almost all missives from her friend “in a fit of caution,”[i] to protect the women’s reputations. But mentions of Mary litter Charlotte’s wider communications, and that of other individuals close to this pair. And when, after the death of Charlotte, another literary friend, Elizabeth Gaskell, was working on the first biography of the famous novelist, Mary sent her pages of recollections. It was Mary’s hope that The Life of Charlotte Brontё could become a vehicle for her own anger at the social restrictions she felt had held Charlotte back throughout her life. But to the forward-thinking Mary’s dismay, Elizabeth, mindful of Victorian notions of propriety, instead portrayed Charlotte as a compliant, saintly figure who suffered her many hardships with acceptance. Stung by the experience, Mary often refused to cooperate with the requests of future biographers. This reticence allowed a more socially acceptable, but less fully-rounded image of Charlotte to emerge. Meanwhile the importance of Mary’s influence on Charlotte’s writing has been allowed to slip away—something that our exploration of their friendship has tried to address.

Unlike Jane and Anne, and Charlotte and Mary—writer friends who enjoyed vastly different levels of recognition—George Eliot and Harriet Beecher Stowe shared an unusual status as the most famous living female authors of their day. In the mid-19th century—as Dickens was fêting the work of Collins—Eliot heaped public praise on this far-off American author who had written Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the era’s great antislavery novel. And so, in 1869, Eliot felt delighted to receive an unexpected letter from Harriet’s home, set amid an orange grove in Florida. She thrilled to her correspondent’s ebullient personality, and—overcoming vast differences in character, opposing views on religion, and the social stigma of Eliot’s “living in sin”—they would soon form a deeply personal attachment. But despite the enduring fame of both women, this compelling friendship remains little known.

One significant, and scarcely believable, factor is that a significant portion of Stowe’s correspondence to Eliot has never made it into print, remaining stored in a locked researchers’ room deep within the New York Public Library. When pieced together with Eliot’s published letters it reveals that, while the two never had the opportunity to meet, on the page they established an epistolary bond that was not only deeply personal but historically significant.

“While Hemingway and Fitzgerald have been remembered as combative friends—these women are often regarded solely as bitter foes.”

Of all the literary collaborations that we have explored, the most complex, perhaps, is that of Virginia Woolf and Katherine Mansfield, who met during the dark days of the First World War, not long before Fitzgerald and Hemingway became friends. Unlike the pairs who came before them, the relationship between Virginia and Katherine, an outsider to the Bloomsbury group, has gone down in history. But for all the wrong reasons. Despite the many affectionate letters and thoughtful gifts they exchanged, their simmering creative rivalry frequently threatened to boil over. And so—while Hemingway and Fitzgerald have been remembered as combative friends—these women are often regarded solely as bitter foes. Yet Katherine and Virginia in fact enjoyed a powerful partnership that would profoundly influence the course of English literature.

Their reams of surviving letters and diaries reveal that, although their alliance was regularly knocked off course by jealousy or misunderstanding, these two ambitious women kept being drawn back to each other through mutual recognition of their shared literary talent. Woolf was deeply hurt when Mansfield publicly criticised one of her novels for failing to acknowledge in form or content the damage inflicted by the First World War. But, in time, Woolf would benefit from Mansfield’s insights. Woolf’s next three books—all war novels—represent a shift to the Modernist style, for which she has been best remembered.

In their friendships, all of these remarkable women overcame differences in worldly success and social class, as well as personal schisms and public scandal. But they could not prevent family members and biographers from missing, ignoring, or even willfully covering up their treasured collaborations.

In piecing together the lost stories of these four trailblazing pairs, we have found alliances that were sometimes illicit, scandalous, and volatile; sometimes supportive, radical, or inspiring—but, until now, tantalizingly consigned to the shadows.

*

[i] “in a fit of caution”: Mary Taylor to Charlotte Brontё, June to 24 July 1848, The Morgan Library & Museum, Joan Stevens (ed.), Mary Taylor, Friend of Charlotte Brontë: Letters from New Zealand and Elsewhere, Auckland University Press, 1972, 75.

__________________________________

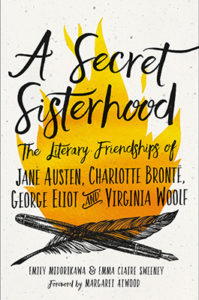

Adapted from the introduction to A SECRET SISTERHOOD: The Literary Friendships of Jane Austen, Charlotte Brontë, George Eliot, and Virginia Woolf. Used with permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Copyright © 2017 by Emily Midorikawa and Emma Sweeney.

Emily Midorikawa and Emma Sweeney

Emily Midorikawa's work has been published in the Daily Telegraph, the Independent on Sunday, and the Times. She is a winner of the Lucy Cavendish Fiction Prize and was a runner-up in the SI Leeds Literary Prize (judged by Margaret Busby) and the Yeovil Literary Prize (judged by Tracy Chevalier). She teaches at New York University–London. Emma Claire Sweeney's work has been published in the Guardian, the Independent, and the Times. She has won Arts Council and Royal Literary Fund Awards, and her debut novel, Owl Song at Dawn, came out to critical acclaim in 2016. She teaches at New York University–London.