The Empire of the Archive: On the Relentless Contemporary Deluge of Images

Maël Renouard: “Today, images come one after another, devour each other, replace each other pitilessly.”

I have the impression, when I look back on it, that my childhood took place in an era of the scarcity of images. Such a characterization would have seemed odd or even inconceivable at the time, for we already believed ourselves to be overwhelmed by a quantity of images never seen since the beginning of the world. And yet how rare they were in comparison to the overabundance we now have at our fingertips. We had to wait for them: wait for the films that were shown once on television and shown again only many years later; wait for the magazines that, once a month, brought a cargo of images that seems meager indeed, now that we can find on the internet, for every object and every desire, about as many images as we could wish.

Images were a luxury that demanded patience. When we had one in our possession, we treasured it; we cut it out, pasted it into an album. From time to time, we went back to it and dreamily gazed at it for a long while. This relative scarcity of images had even made them into a kind of schoolyard currency—a currency now considerably devalued through overinflation. Today, images come one after another, devour each other, replace each other pitilessly, as if to outmatch the boundlessness of our desire.

There are so many images of everything nowadays that we have always already seen what we are about to see—be it an apartment for rent, the hotel in which we are going to spend a few nights for the holidays, the man we are supposed to meet for an interview, etc. Physical space is becoming the arena of a kind of general recognition where we go to meet up with images and verify what they have promised. More and more, we compare reality to images, instead of comparing images to reality.

Looking back to the 1980s or 1990s, I can’t help thinking that we would have greeted this phenomenon as a miracle at the time—especially if it had arisen all at once, suddenly, and not in the course of a gradual process of technological evolution whose duration, though relatively brief, was sufficient to dull our capacity for astonishment.

The first time I visited the Greek island of Hydra, in August 2000, I don’t think I had seen a single image of it beforehand, neither in a book, a newspaper, on television, nor anywhere else. I can’t be completely sure of this, to tell the truth, but when I dig through my memory, I don’t find anything that contradicts this total absence of preliminary images. The travel guide that I had back then contained no photographs; it offered only a basic map—a faulty one, for that matter—of the island. (I could have seen a fairly large photograph of the port with its village rising behind like an amphitheater in Routes de Méditerranée by Alain Grée, a sailing book published in the 1980s, but I only got hold of it one or two years after my visit.) It hardly matters.

This uncertainty itself confirms my suspicion that I haven’t greatly suffered from the loss of this experience of surprise, of pure discovery, of not knowing what to expect—a suspicion which, as I began to bring it to light and analyze it, immediately seemed firmly anchored in me and at the same time fairly odd, for we are accustomed to feeling wistful for the little frailties that made our prior condition more humble, more “authentic,” and to being wary of the new powers that technology has granted us. Incidentally, I’ve never heard anyone else lament this loss, or even notice it, to tell you the truth.

The proliferation of images hasn’t detracted from the singularity of reality, its force, its imprint. No matter how many hundreds of images we have of the place where we are heading, the fact of being there remains an experience that contains something entirely different—not unlike Kant’s example of the hundred thalers, the concept of which is the same regardless of whether or not they are in my pocket, but the existence of which changes everything. Images, no matter how abundant, continue to create a desire for things, a desire for the coming into being of that which is imaged. This was already apparent in the pre-digital age, when things that had images were often more desirable than things unable or unwilling to display themselves.

*

When we used to miss an appointment with an image, we had very little chance of someday crossing paths with it again. Images weren’t merely rare but ephemeral. Only a very small, elect circle had access to the Institut National de l’Audiovisuel. A person who missed the televised evening news on March 23, 1972, can now watch and rewatch it endlessly, if he wishes, as easily as the news of today, in the digital expanse that is the place of the integral resurrection—and exhibition—of images.

*

“The Artist of the Last Day,” a prose poem by Yves Bonnefoy—published in 1987 in Rue Traversière et autres récits en rêve—evokes an imminent end of the world provoked by a kind of deluge of images. “The world was going to end suddenly because—a voice seemed to prophesy—in a few weeks, in a few days, perhaps in a few hours, the number of images produced by humanity would have surpassed the number of living creatures.” Bonnefoy constructed an entire poetics—so articulated, ramified, and, as it were, systematic, that we could equally call it a philosophy—in which the notions of image, dream, illusion, and melancholy are attacked in the name of a quest for presence and simplicity. This text is one of the most beautiful instances of such a poetics; but the at least provisional defeat of the cause he championed has come to pass. The number of images has exceeded anything we could have imagined in 1987. The empire of the archive has planted its melancholy flag in the last bastions of the iconoclastic defenders of presence.

*

Images were a luxury that demanded patience.

Leibniz stated the hypothesis of a “horizon of human knowledge” from which one can deduce the necessity of eternal return. He, as it were, toyed with this hypothesis without our being able to affirm that he made it his own. His reasoning was more or less as follows: Every event can give rise to a statement. And there exists a total number of statements that can be formed from the letters of the alphabet. No matter how large, such a number is well and truly finite, just as the staggering number of grains of sand in the desert is finite. In one text, Leibniz established the outer limit—the horizon—at 107300000000000, below which must lie the exact number of all possible statements. A day will therefore arrive when everything has been said, when it will no longer be possible to say anything that hasn’t already been said. Then, by virtue of the correspondence between deeds and words, no event will be able to take place that hasn’t already occurred as well. The world will have exhausted its stock of events. It will end, and begin again.

*

This immense finitude can be glimpsed in the permanent accumulation of signs registered at every instant by the internet while the world goes on turning, a record in which one finds deposited, in the form of alphabetic statements, even the smallest mental or emotional events that rise to the consciousness of hundreds of millions of individuals.

*

In Guy Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle, a critique of established political-economic systems—whether Soviet bureaucratic or liberal democratic—coexists with a pure philosophy, according to which the authenticity of life has to be reconquered in place of the images that have severed it from themselves. (Its fundamental premise bears an affinity with the thought of the Christian phenomenologist Michel Henry.) At the heart of this philosophy is a nostalgia for presence. “Everything that was directly experienced has withdrawn into a representation.” The images that have detached themselves from life reconstitute themselves as a separate world, which life can only gaze upon by rending its own unity. Debord associates these two dimensions, the political and the metaphysical: behind the self-dispossession that existence suffers, a monopolistic power is at work, manipulating the spectacular in order to maintain and expand itself. The powerful impression created by his book lies in the convergence of these two dimensions. This, in a certain way, is what gives the book its timeless lyricism, its stylistic alchemy. It elevates to the highest degree the nature of these struggles whose final motto is: negation of the spectacular negation of life; radical detachment from the world of detachment.

The internet has split apart these two dimensions. It has increased the flow of images that duplicate life, but it has given each individual the power to emit them, thus breaking up the great spectacular monopolies. Debord died in 1994, the year in which the first internet providers appeared in France. We shall forever regret the loss of the new “commentaries upon the society of the spectacle” that he would surely have devoted to this technology as he sought to determine to what extent it has overthrown the paradigm that his critical thought opposed (as one cannot but assume is the case). As the spectacular monopolies were collapsing, the world of representation continued to expand while falling into disarray. Conspiracy theories were the first phase of a belief in liberty regained, the lever that toppled the transmission towers of institutional broadcasters. Debord spoke of the diffuse spectacle (liberal democratic) and the concentrated spectacle (Soviet). Perhaps we should invent the category of the esoteric spectacle (digital) in which life hands itself the mirror of a false reconciliation.

More and more, we compare reality to images, instead of comparing images to reality.

In the concluding lines of his long preface to the Italian edition of The Society of the Spectacle—published in 1979, 12 years after the French edition—Debord seems to anticipate the atmosphere of a latent war whose theater is now the internet: “Under each result and under each project of an unfortunate and ridiculous present, we see inscribed the Mene, Tekel, Upharsin that announces the inevitable fall of all cities of illusion. The days of this society are numbered; its reasons and its merits have been weighed in the balance and have been found wanting; its inhabitants are divided into two sides, one of which wants this society to disappear.” This writing on the wall shows through in the insults directed each day at traditional media, vestiges of the diffuse spectacle descended into the digital arena. But the struggles unfolding before our eyes hardly seem to portend life’s victory over representation. The partisans of pure criticism are so persuaded of being in direct contact with the truth that they do not see the new illusion into which they have shut themselves. We have no dialectic by which to set these incomplete figures back into their place.

It’s hard to tell if Debord would have detected emancipatory virtues in the internet or if he would have seen it as a new form of spectacle. One might surmise that his fundamental metaphysical thesis would incline him toward the latter. This thesis is so radical that it is essentially inalterable. For, since the beginning, everything that was directly experienced has withdrawn—into a memory. In a philosophy of recollection—or of the internet as an immense recollection machine—life reunites with itself only in the separate world of memories, melancholically.

For the Scholastics, the angels were a kind of experimental being endowed with the perfections that humanity judged itself to lack. These hypotheses, or, so to speak, these fictions, revealed all sorts of difficulties, paradoxes, or impasses, on a moral or metaphysical level, which gave rise to endless controversies that we would be wrong to continue to ridicule too much today, not only because they often have a real literary merit but also and above all because we—who have come face-to-face with our own perfection—can find questions there that resonate with our own situation, present or future, and that are paradoxically more relevant to us than they were to the men of the Middle Ages who formulated them.

I’m not well versed enough in theology to know if anyone has ever attributed to angels the ability to see themselves from without as others see them. (Perhaps the question never arises, since angels don’t have bodies; or perhaps it does arise, precisely for that reason.) It’s easy in any case to see this as something that is missing from our experience, a faculty our condition lacks. I remember how strange I felt the first time I used Skype. What troubled me wasn’t the image of my interlocutor speaking to me from the other end of the earth—after all, science fiction had so long familiarized us with this dream of the videoconference that it didn’t affect us much when it became possible. What troubled me was the other image, the little image at the bottom right, where I saw myself speaking; and even more specifically, what troubled me was the vague presentiment I had of witnessing, in this splitting of perception, something that would one day become a permanent and, as it were, commonplace element of our existence.

In fact, all it takes to make this daydream concrete is to imagine that ultra-miniaturized drones accompany us at every moment, transmitting images of us to a Google Glass–type device, or better yet, in a slightly more distant future, transmitting them to the post-digital internet within our minds to which we would have access—without any exterior device—by a pure act of spirit.

____________________________

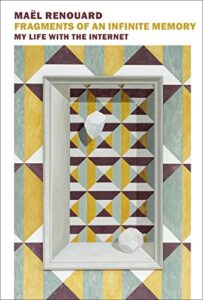

Adapted from Fragments of an Infinite Memory: My Life With the Internet by Maël Renouard, translated from the French by Peter Behrman de Sinéty. Copyright (c) 2021. Reprinted with the permission of the publisher, New York Review Books.

Maël Renouard

Maël Renouard is a novelist, essayist, and translator. He has taught philosophy at the Sorbonne and the École Normale Supérieure on the rue d'Ulm, of which he is a graduate. His novella La Réforme de l'opéra de Pékin (The Reform of the Peking Opera) received the Prix Décembre in 2013, and his novel L'Historiographe du royaume (The Historiographer of the Kingdom) was named a finalist for the 2020 Prix Goncourt.