The Canonization of Dylan Thomas

On the Legacy of Literary Afterlives

I delight in a palpable imaginable visitable past—in the nearer distances and the clearer mysteries, the marks and signs of a world we may reach over to as by making a long arm we grasp an object at the other end of our own table. The table is the one, the common expanse, and where we lean, so stretching, we find it firm and continuous. That, to my imagination, is the past fragrant of all, or of almost all, the poetry of the thing outlived and lost and gone, and yet in which the precious element of closeness, telling so of connections but tasting so of differences, remains appreciable.

We are divided, of course, between liking to feel the past strange and liking to feel it familiar; the difficulty is, for intensity, to catch it at the moment when the scales of the balance hang with the right evenness.

*

That’s Henry James in the preface to The Aspern Papers, a story about a literary critic’s Venetian quest to acquire a dead poet’s papers. This story doesn’t have a lot in common with James’s, but they are both ghost stories, with ghosts who don’t so much haunt the proceedings as hover just out of reach. As with James’s poet, Jeffrey Aspern, you will not meet Dylan Thomas in this story, nor hear his poems. As with James’s poet, Dylan is dead right from the start. But his afterlife does not exist without the poetry.

James’s idea of a past we can visit as readily as reaching resonates with my work as director of the Unterberg Poetry Center of New York’s 92nd Street Y, only it’s not a table that is the common expanse, firm and continuous, but a stage in a concert hall where for nine decades the finest dancers, musicians and writers have performed and where, if they are lucky, artist and audience grow old together. Looking up from the floorboards at stage center, one sees inscriptions of 19 names in gold leaf, figures of cultural memory—among them Moses, Isaiah, Homer, Virgil, Washington, Lincoln, Beethoven, Bach, Shakespeare, Dante and Goethe—which, like Petrarch’s laurels, crown the heads of artist and audience alike in a canonical tradition established over thousands of years, the Bible and American history on one hand, philosophy, classical music and poetry on the other.

Since 1930, when the hall was built, only one of the 19 names has been swapped—Einstein in, Aristotle out—but no local canon can be fully trusted, certainly not one without women and Mozart. Perhaps our forefathers simply ran out of room, and that’s largely the point. “Cultural memory is defined by a notorious shortage of space,” writes Aleida Assman. “Whatever makes it into active memory has passed rigorous processes of selection. The canon outlives generations.”

Einstein, who died in 1955, is the youngest to be inducted into the hall’s golden crown of names, and no one is suggesting that Dylan replace Dante. But since his tragic death, in 1953 in New York, at the age of 39, on the fourth and final of his Poetry Center-sponsored reading tours, Dylan Thomas has perhaps moved closer than any poet since Yeats to a kind of secular canonization and to becoming, in his home country of Wales, a national poet and cultural saint. Here on the day after the third-annual Dylan Day, a literary holiday created by the Welsh in the commemorative momentum of the poet’s 2014 centenary, I’d like to explore this idea—what it is, how it happened and what it means. Cultural canonization—the social construction of immortality—is “meant to be a suggestive concept,” write Marijan Dovic and Jon Karl Helgason in their new study, National Poets, Cultural Saints. “It allows for a simultaneous focus both on the cultural saints and those who manage their afterlives.” Since producing celebrations of Dylan’s centenary in 2014, I have become fascinated by the story of his afterlife and its stewardship in the last six decades, both at the Y and in Wales.

Dovic and Helgason’s new study expands on their contributions to the anthology Commemorating Writers in 19th-century Europe, whose editors, Joep Leersen and Ann Rigney, argue that:

The resolutely textual focus of traditional literary scholarship has meant very little critical attention has been paid until recently to these extraordinary performances and materializations of literary enthusiasm in the public sphere. But with the recent broadening of the scope of scholarship to processes of reception and to the ‘social lives of texts,’ the full scale of their importance emerges: they indicate that canonicity is not merely a matter of which books are kept on the bookshelves, but also a matter of the way people give shape to their collective identities and allegiances in a public way. The picture which emerges is one of a complex interaction between the embodied and the imagined experience of communities, between the local and the national celebration of a common figure and between the different localities participating in the same cult.

The anthology looks at the public literary celebrations of Schiller and Burns, Walter Scott, Dante, Voltaire, Pushkin, Cervantes, and Shakespeare, among others, and defines cult as “a pattern of ritual behavior in connection with specific objects within a framework of spatial and temporal coordinates [with] some degree of recurrence in place and repetition over time of ritual action.” The 92nd Street Y, it turns out, is one of the founding sites of the Dylan Thomas cult, together with the city of Swansea, where Dylan was born and raised, writing the poems that made his name in the literary circles of 1930s London; and the town of Laugharne, where he is buried in St. Martin’s cemetery and where he lived with his wife Caitlin and three children the last four years of his life, composing “Over St. John’s Hill,” “Do Not Go Gentle,” “Poem on His Birthday” and most of Under Milk Wood in a writing shed looking out across the Taf Estuary.

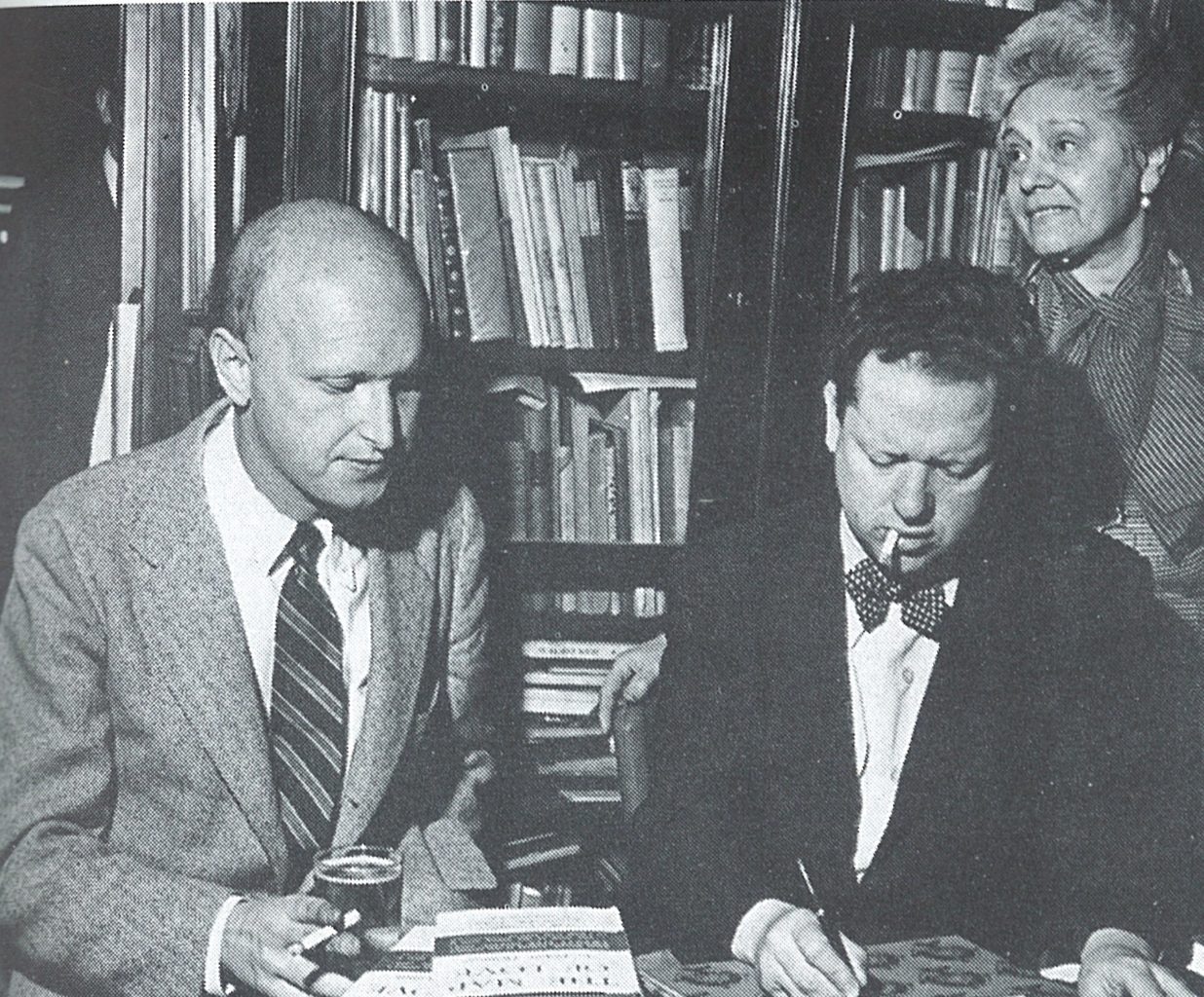

It was John Malcolm Brinnin, my long-ago predecessor as director of the Poetry Center from 1949 to the mid-1950s, who first brought Dylan to America. The first thing Brinnin did after he was hired, now that he had institutional backing, was invite Dylan to read at the Y. Dylan had been hoping to come to the States since the end of World War II, but he said he would need a number of paid gigs to make the trip worthwhile. In 1949 he was little known in America beyond literary circles, and Brinnin struggled to find a booking agent who would take him on. In an exchange that would forever alter both men’s lives, Dylan accepted Brinnin’s offer to plan the tour himself.

John Malcolm Brinnin and Dylan Thomas at Gotham Book Mart. Photo by G.D.Hackett 1952

John Malcolm Brinnin and Dylan Thomas at Gotham Book Mart. Photo by G.D.Hackett 1952

There would be four cross-country tours, all told, with Dylan gracing our stage 12 times between 1950 and 1953, including four performances of Under Milk Wood, the first of which, on May 14, 1953, was the full play’s premiere. The Poetry Center played its role in Dylan’s rise to fame and has continued to do so at regular intervals, often anniversaries of his birth or death, during his afterlife. A tribute reading of Under Milk Wood in February 1954 to raise money for his family fund—he died destitute the previous November—was followed by a 1964 ceremony that deepened our connection to Wales. Two days after Dylan’s death, sculptor David Slivka had snuck into a Manhattan funeral home to make a mask of Dylan’s face and head. “I knew the beauty of that head,” Slivka later said. He felt a need to preserve his friend’s visage, as had been done with Keats, Dante and Goethe. He made a five-piece mold and then from a plaster cast created a bronze bust of Dylan that he left on the terrace of his West Village apartment for the next ten years. Slivka’s apartment, at 107 Bank Street, was one block north of Dylan’s beloved White Horse Tavern.

Richard Burton at 1964 ceremony.

Richard Burton at 1964 ceremony.

On the afternoon of Sunday, May 24, 1964, a few months before what would have been Dylan’s 50th birthday, the Y hosted a ceremony at which the bust was gifted to the National Museum of Wales. Richard Burton, on break from playing Hamlet on Broadway, read his friend’s poems, and Brinnin spoke, too. Having left the Poetry Center in the aftermath of Dylan’s death and written Dylan Thomas in America, a controversial memoir that ensured he’d always be haunted by the association, Brinnin was making his first appearance on our stage in a decade.

“We have survived him as, we know, his memory will survive us,” Brinnin said that day. “And yet I think it is important to remember that, in the curious operations of time, immortality is something that is always conferred—a gesture, so to speak, that identifies not only those who receive it, but those who give it. Dylan had the humility—the profound humility—that is felt only by the most gifted of artists because they are the only ones who finally understand what they might do and what they have not done.”

Slivka eventually made five bronze busts and for a while one of them was on display in the Y’s art gallery. That bust now lives on my desk. When, some fifty years after Brinnin’s speech, on the occasion of the 2014 centenary, it came time to play my part as steward, the Poetry Center produced a revival of Under Milk Wood with Michael Sheen and a group of Welsh actors including Kate Burton, Richard Burton’s daughter. Here is how Sheen introduced that Sunday-afternoon performance, whose crowd included some patrons who’d attended the play’s 1953 premiere. Thanks to a live BBC radio broadcast, a large Welsh audience was listening in, too.

When, back in 1978, the BBC sent a film crew to our concert hall to shoot scenes of a documentary to mark the 25th anniversary of Dylan’s death, the producer wrote to another of my predecessors asking if the original stools and music stands from the 1953 premiere were still around. On the day of the shoot, with an actor on stage impersonating Dylan, hundreds of Poetry Center subscribers were invited to dress up in vintage outfits, sit in the audience and play 1950s versions of themselves. “Memorials of writers and national poets in particular have regularly functioned as sacred places where various forms of rituals—pilgrimages, centenaries, annual festivities, processions, wreaths, proclamations—were performed,” write Dovic and Helgason. “These memorials provide a spatial framework for the evolving cult of cultural saints, enabling many people to express their loyalties by participating in collective rites.”

In 1982, when Dylan was inducted into Westminster Abbey’s Poets’ Corner, Brinnin was there and filed this report for The New Yorker:

Welcoming the gathering of some 1500 or so, the Dean of Westminster provided a fact that did not seem entirely pertinent,” he wrote. “While Keats, Shelley and Byron each had to wait almost a hundred years to be honored with a stone at Poets’ Corner, Browning and Tennyson came by theirs almost instantaneously. As I calculated that Dylan, were he alive today, would be 67 years old and younger than perhaps a third of those who’d come to do him homage, the woman next to me touched my elbow. ‘I should venture waiting 29 years is quite long enough,’ she whispered. Outside, a bit stunned by the actuality of it all, the discrepancy between that radiant stone and Dylan’s often expressed wish never to be anything but ‘lost and proud’—and, I must admit, having a few valedictory thoughts of my own—I was buttoning my overcoat against the cold sunlight when I found myself next to a man holding a little girl. Blue-eyed, with fair hair cut in the demure permanent-wave manner of the 1920s, she stared at me over his shoulder for a few seconds, then reached out a small white hand. As I brought my index finger to within an inch of hers, she took hold, tightened her grip, and would not let go until the man, shifting the weight of her to his other shoulder, turned around. ‘This is Dylan’s granddaughter,’ he said. ‘Her name is Hannah.’

Aeronwy Thomas (daughter) at Poets’ Corner Stone Unveiling–March 1, 1982

Aeronwy Thomas (daughter) at Poets’ Corner Stone Unveiling–March 1, 1982

*

Like Petrarch’s Arqua, Shakespeare’s Stratford and Jane Austen’s Chawton, Dylan’s Swansea and Laugharne are central to the cult that has emerged in the six decades since his death. In Laugharne, pilgrims visit Dylan’s grave, his boathouse, writing shed, and favorite pubs. They take walking tours of natural sites that inspired him all his life in southwest Wales. Brinnin made his own trip in 1963. “Dylan’s walk is as it was,” he wrote in his diary. “The green shack”—his writing shed—“has been cleaned out and padlocked. The way down to the boathouse is weedier than ever. Who lives there? Whoever they are, they like pop music in the middle of the day and have striped deck chairs in what’s left of the garden.”

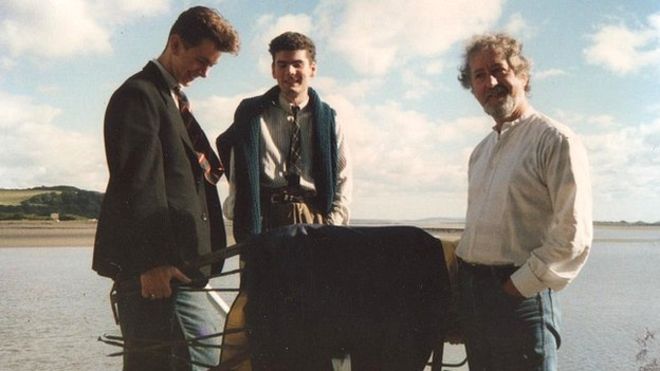

In 1955 Caitlin Thomas had received permission to have Dylan’s body reburied in the garden of the boathouse, but this was never done. Dylan’s mother Florence lived there until her own death in 1958, and it was then rented out. Eventually it was bought by the local council and restored as a museum. You can now have lunch on the deck overlooking the estuary. Strangely enough, the original gate to the boathouse was once discovered washed up on the nearby beach by a young Michael Sheen.

Michael Sheen (left) with original Boathouse gate in 1984.

Michael Sheen (left) with original Boathouse gate in 1984.

Dylan’s writing shed, a converted garage, was ransacked after his death. It, too, is now owned by the council, which has reconstructed it over the years and furnished it with forged relics such as Dylan’s chair and jacket, scraps of paper, books and photos of his favorite artists and works of art. During the centenary, a replica of the replica of the shed was put on wheels and toured the UK, stopping at schools to give students a glimpse of the place where Dylan wrote his last poems and some of Under Milk Wood.

Interior of reconstructed Dylan Thomas writing shed in Laugharne.

Interior of reconstructed Dylan Thomas writing shed in Laugharne.

Dylan’s birthplace in Swansea, where he lived the first half of his life, follows a similar story of neglect and restoration. The current owner has reconstructed its interiors to look as they did when the Thomases lived there, including Dylan’s bedroom faithfully kitted out with a starter set of the same sorts of relics—cigarette packs and candy wrappers—found in the writing shed. Guests can spend the night in a room down the hall from where Dylan was born.

The Poetry Center, the boathouse and the birthplace all belong to what Dovic and Helgason, in their framework of cultural canonization, call the cultus: “the agents and social networks that direct the complex processes of collective memory.” If vita accounts for an author’s contribution in his or her lifetime to qualify for canonization—not just one’s writing but lifestyle and reputation, mystery and suffering (all self-evident in the case of Dylan Thomas)— the cultus is responsible for the “posthumous voyage of the author and his or her legacy.”

Relics—and the question of their authenticity—are a “constant, often obsessive concern,” they write. “Imitating the common practice of translation, which was central to Christian saintly cults, the cultural saint’s personal possessions are often moved to a more prestigious location, repatriated to the ‘homeland,’ or put on display. There is pious concern, too, over the material artistic legacy (artworks, books, furniture, accessories).”

During the centenary, a previously unknown notebook of Dylan’s from the 1930s—its discovery hailed as the “holy grail” in newspapers—was bought at auction for 100,000 pounds by Swansea University. Dylan had left the notebook behind on a visit to Caitlin’s mother, Yvonne MacNamara, who gave it to the housekeeper with instructions to burn it. The housekeeper kept it instead, and it’s now part of the university’s Richard Burton archives.

Hannah Ellis’s chief objective during the centenary was—and remains—re-introducing Dylan into the school curricula at all levels across the UK, both in English and Welsh translation. “We’ll be looking at the wizardry of Dylan’s writing to show how anyone can be creative using their imagination and the characters from where they live,” she has said. Hannah herself did not encounter her grandfather’s work during her school years. “It’s the continuous dissemination of sets of given ideas over many generations provided by the educational system that can be seen as the single most effective means of reproducing the canonical status of cultural saints,” write Dovic and Helgason.

Inspired by Bloomsday and Burns Supper, the idea of Dylan Day has been floated for decades, but critical mass occurred only on the heels of the centenary. May 14 was chosen not because it’s Dylan’s birthday or death day, but because it’s the day, in 1953, when he premiered Under Milk Wood on stage at the 92nd Street Y. The Welsh government has pledged funds to promote Dylan Day internationally, but its support will soon expire.

The last category in Dovic and Helgason’s analytical framework is called effectus, which refers to the social consequences of cultural canonization, including changes to the calendar and development of public spaces. Like the bronze bust of Dylan that lives on my desk, there is a statue of him on display in Dylan Thomas Square in Swansea. In 2009, as part of a publicly funded project, Estonian artist Neeme Kulm, looking “to provoke a heightened awareness of what has become too familiar to even notice, asked how the city would be affected if the poet were to disappear.”

Installation of Neeme Kulm’s Sculpture Concealing Dylan Thomas Sculpture – 2009

Installation of Neeme Kulm’s Sculpture Concealing Dylan Thomas Sculpture – 2009

“As the performative aspect of the term ‘remembrance’ suggests, collective memory is constantly in the works,” writes Ann Rigney. “Like a swimmer, it has to keep moving to remain afloat. To bring remembrance to a conclusion is de facto to forget. While putting down a monument may seem like a way of ensuring long-term memory, it may in fact turn out to mark the beginning of amnesia unless the monument in question is continuously invested with new meaning.”

Recently the local politicians of Laugharne approved plans to erect a 147-foot wind turbine on a hill across the Taf Estuary, maligning the view from the boathouse and writing shed. The turbine was not a part of Dylan’s view and should not be there now, was the argument loudly voiced by the opposition, including Hannah Ellis. The politicians lost in the court of public opinion and eventually lost in actual court, too. There will be no turbine.

Statue of Dylan Thomas in Laugharne.

Statue of Dylan Thomas in Laugharne.

I have now made my own pilgrimage to Laugharne, which surely features the most haunting of memorial statues, a figure with no resemblance to the iconic Dylan of his day, as if the sculptor had worked from the wrong model. Unless it’s something more like wishful thinking: a desire to manifest a Dylan who did not die young. What laurels would Dylan the elder have received? Here is one idea.

Dylan Thomas, at the age of 73, stands well within the company of the great poets. He is still writing, and the poems which now appear, usually embedded in short plays or set into the commentary and prefaces which have been another preoccupation of his later years, are, in many instances, as vigorous and as subtle as the poems written by him during the years ordinarily considered to be the period of a poet’s maturity.

The early Thomas was, in many ways, a youth of his time: a romantic exile seeking, away from reality, the landscape of his dreams. By degrees—for the development took place over a long period of years—this partial personality was absorbed into a man whose power to act in the real world and endure the results of action (responsibility the romantic hesitates to assume) was immense. Thomas advanced into the world he once shunned, but in dealing with it he did not yield to its standards. That difficult balance, almost impossible to strike, between the artist’s austerity and “the reveries of the common heart”—between the proud passions, the proud intellect and consuming action—he finally attained and held to.

In age, he shows no impoverishment of spirit or weakening of intention. He answers current dogmatists with words edged with the same contempt for “the rigid world” of materialism that he used in youth. He is now content to throw out suggestions that are not, perhaps, for our age to complete, as it is not for our age fully to appreciate a man who reiterates: “If we have not the desire of artistic perfection for an art, the deluge of incoherence, vulgarity, and triviality will pass over our heads.” Adherence to that creed, and that creed alone, has given us the greatest poet writing in English today.

These are the words of Louise Bogan, whose poems Dylan used to read as part of his public performances at places like the Y. Dylan enjoyed performing others’ poems more than his own. He wrote them out longhand to learn their music and embody them with his voice. Bogan is not writing about Dylan, though. She is writing about Yeats. Her essay of appreciation was published in 1938, when Yeats turned 73. He died a year later, in 1939. The year the Poetry Center was born.

Bernard Schwartz

Bernard Schwartz is director of the 92nd Street Y's Unterberg Poetry Center. His research on the legacy of literary afterlives has been supported by a fellowship from Queen Mary University and conversations with Hannah Ellis over pints of Guinness at The Wheatsheaf.