Read It and Weep: Margaret Atwood on the Intimidating, Haunting Intellect of Simone de Beauvoir

On the French Existentialist's Never-Before-Published Novel

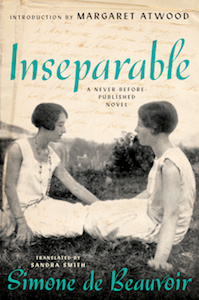

How exciting to learn that Simone de Beauvoir, grandmother of second-wave feminism, had written a novel that had never been published! In French it was called Les inséparables and was said by the journal Les libraires to be a story that “follows with emotion and clarity the passionate friendship between two rebellious young women.” Of course I wanted to read it, but then I was asked to write an introduction to the English translation.

My initial reaction was panic. This was a throwback: as a young person, I was terrified of Simone de Beauvoir. I went to university at the end of the 50s and the beginning of the 60s, when, among the black-turtleneck-wearing, heavily eyelinered cognoscenti—admittedly not numerous in the Toronto of those days—the French Existentialists were worshipped as minor gods. Camus, how revered! How eagerly we read his grim novels! Beckett, how adored! His plays, especially Waiting for Godot, were favorites of college drama clubs. Ionesco and the Theatre of the Absurd, how puzzling! Yet his plays, too, were often performed among us (and some, such as Rhinoceros—a metaphor for fascist takeovers—are increasingly pertinent).

Sartre, how bafflingly smart, though not what you’d call cute. Who hadn’t quoted “Hell is other people”? (Did we recognize that the corollary would have to be “Heaven is solitude”? No, we did not. Did we forgive him for having sucked up to Stalinism for so many years? Yes, we did, more or less, because he’d denounced the invasion of Hungary by the U.S.S.R. in 1956, then had written an incandescent introduction to Henri Alleg’s The Question (1958), an account of Alleg’s brutal torture at the hands of the French military during the Algerian war—a book banned in France by the government but available to us in the boonies, as I read it in 1961.)

But among all these intimidating Existentialist luminaries there was only one female person: Simone de Beauvoir. How frighteningly tough she must be, I thought, to be holding her own among the super-intellectual steely brained Parisian Olympians! It was a time when women who aspired to be more than embodiments of assigned gender roles felt they had to comport themselves like macho men—coldly, with avowed self-interest—while seizing the initiative, even the sexual initiative. A bon mot here, a slapping away of a wandering hand there, an insouciant affair, or two, or 20, followed by cigarettes, as in films… I never would have been up to it, struggling as I was with the lesser demands of the college debating club. In addition to which, smoking made me cough. As for those dowdy wartime suits with the durability and the shoulder pads, those would have been far too high a price to pay for a room of one’s own.

Why was Simone de Beauvoir so frightening to me? Easy for you to ask: you have the benefit of distance—dead people are less innately scary than living ones, especially if they’ve been cut down to size by biographers, ever alert to flaws—whereas for me, Beauvoir was a giant contemporary. There was the 20-year-old me in provincial Toronto, dreaming of running away to Paris to compose masterpieces in a garret while working as a waitress, and there were the Existentialists, holding court at Le Dôme Café in Montparnasse, writing for Les temps modernes, and sneering at the likes of mousy me. I could imagine what they might say. “Bourgeoise,” they would begin, flicking the ashes off their Gitanes. Worse: Canadian. “Quelques arpents de neige,” they would quote Voltaire. Moreover, a Canadian from the backwoods. And the worst kind of backwoods Canadian: an Anglo. The dismissive contempt! The sophisticated disdain! There is no snobbism quite like French snobbism, especially that of the Left. (The Left of the mid-20th century, that is; I am sure no such thing would happen now.)

But then I grew somewhat older, and I actually went to Paris, where I was not rejected by Existentialists—I couldn’t find any, as I couldn’t afford to eat in Parisian cafés—and shortly after that I was in Vancouver, where I finally read The Second Sex from cover to cover, in the washroom so no one would see me doing it. (The year was 1964, and second-wave feminism had not yet arrived in the hinterlands of North America.)

Why was Simone de Beauvoir so frightening to me?

At this point, some of my terror was replaced by pity. What a strict upbringing had been imposed upon the young Simone. How constrained she had felt, in her supervised body and frilly girl’s clothing and rigidly prescribed social behavior. It seemed that there were advantages to being a backwoods Canadian girl after all: free from censorious nuns and demanding sets of highish-society relatives, I could run around in trousers—better than skirts, considering the mosquitoes—and paddle my own canoe and, once in high school, attend sock hops and go rollicking off to drive-in movies with slightly disreputable boyfriends. Such unconstrained and indeed unladylike comportment never would have been permitted to the young Simone. The strictness was for her own good, or so she would have been told. If she violated the rules of her class, ruin would await her, and disgrace would be the lot of her family.

It’s worth reminding ourselves that France did not grant the vote to women until 1944, and then only through a law signed by Charles de Gaulle in exile. That’s almost 25 years after most Canadian women gained the same right. So Beauvoir grew up hearing that women, in effect, were unworthy of having a say in the public life of the nation. She would have been 36 before she could vote, and then only in theory, since the Germans were still in control of France at that time.

Once she came of age, during the 20s, Simone de Beauvoir reacted strongly against her corseted background. I, being much less corseted, did not feel that the conditions described in The Second Sex applied to all women. Some of the book rang true to me, to be sure. Though by no means all of it.

In addition, there was the generation gap: I was born in 1939, whereas Beauvoir was born in 1908, a year before my mother. They were of the same cohort, though worlds apart. My mother grew up in rural Nova Scotia, where she was a tomboy, a horseback rider, and a speed skater. (Try to picture Simone de Beauvoir speed skating and you will grasp the difference.) Both had lived through World War I as children and World War II as adults, though France was at the center of both, and Canada—though its wartime military losses were greatly out of proportion to its population—was never bombed and never occupied. The hardness, the flintiness, the unflinching stare at the uglier sides of existence that we find in Beauvoir are not unconnected to France’s ordeals. Enduring these two wars, with their privations, dangers, anxieties, political infighting, and betrayals: that passage through hell would have taken its toll.

Thus my mother lacked the flinty gaze, having instead a cheerful, roll-up-your-sleeves, don’t-whine practicality that would have seemed offensively naive to any mid-century Parisian. Overcome by the oppressiveness of existence? Faced with a large rock that Sisyphus must roll uphill, only to have it roll down again? Plagued by the existential tension between justice and freedom? Striving for inner authenticity or, indeed, for meaning? Worried by how many men you’d have to sleep with in order to wipe the stain of the haute bourgeoisie from yourself forever? “Take a nice brisk walk in the fresh air,” my mother would have said, “and you’ll feel a lot better.” When I was waxing too depressingly intellectual and/or morose, this was her advice to me.

My mother wouldn’t have been very interested in the more abstract and philosophical portions of The Second Sex, but I expect she would have been intrigued by much of Simone de Beauvoir’s other writing. From this distance it’s arguable that Beauvoir’s freshest and most immediate work comes directly from her own experience. Again and again she felt drawn back to her childhood, her youth, her young adulthood—exploring her own formation, her complex feelings, her sensations of the time. The best-known example is perhaps the first volume of her autobiography, Mémoires d’une jeune fille rangée (1958), but the same material appears in stories and novels. She was, in a sense, haunted by herself. Whose invisible but heavy footfall was that, coming inexorably up the dark stairway? It usually turned out to be hers. The ghost of her former self, or selves, was ever present.

And now we have a wellspring of sorts: Inseparable, unpublished until now. It recounts what was perhaps the single most influential experience of Beauvoir’s life: her relationship with “Zaza”—the Andrée of the novel—a many-layered and intense friendship that ended with Zaza’s early and tragic death.

Beauvoir wrote this book in 1954, five years after publishing The Second Sex, and made the mistake of showing it to Sartre. He judged most works by political standards and could not grasp its significance; for a materialist Marxist, this was odd, as the book is intensely descriptive of the physical and social conditions of its two young female characters. At that time the only means of production taken seriously had to do with factories and agriculture, not the unpaid and undervalued labor of women. Sartre dismissed this work as inconsequential. Beauvoir wrote of it in her memoir that it “seemed to have no inner necessity and failed to hold the reader’s interest.” This appears to have been a quote from Sartre, one with which Beauvoir appears to have agreed at the time.

Well, Dear Reader, Mr. “Hell is other people” Sartre was wrong, at least from this Dear Reader’s perspective. I suppose that if you’re keen on abstractions such as the Perfection of Humankind and Total Justice and Equality, you won’t like novels much, since all novels are about individual people and their circumstances; and you particularly won’t like novels written by your lady love about events that have taken place before you yourself have manifested in her life, and that feature an important, talented, and adored Other who happens to be female. The inner life of young girls of the bourgeoisie? How trivial. Pouf. Enough with this small-scale pathos, Simone. Turn your well-honed mind to more serious matters.

Ah, but M. Sartre, we reply from the 21st century, these are serious matters. Without Zaza, without the passionate devotion between the two of them, without Zaza’s encouragement of Beauvoir’s intellectual ambitions and her desire to break free of the conventions of her time, without Beauvoir’s view of the crushing expectations placed on Zaza as a woman by her family and her society—expectations that, in Beauvoir’s view, literally squeezed the life out of her, despite her mind, her strength, her wit, her will—would there have been a Second Sex? And without that pivotal book, what else would not have followed?

Furthermore, how many versions of Zazas are living on the earth right now—bright, talented, capable women, some oppressed by the laws of their nations, others through poverty or discrimination within supposedly more gender-equal countries? Inseparable is particular to its own time and place—all novels are—but it transcends its own time and place as well.

Read it and weep, Dear Reader. The author herself weeps at the outset: this is how the story begins, with tears. It seems that, despite her forbidding exterior, Beauvoir never stopped weeping for the lost Zaza. Perhaps she herself worked so hard to become who she was as a sort of memorial: Beauvoir must express herself to the utmost, because Zaza could not.

Read an excerpt from Inseparable here.

__________________________________

From Inseparable by Simone de Beauvoir. Introduction copyright © 2021 by Margaret Atwood. Excerpted by permission of Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Margaret Atwood

Margaret Atwood, whose work has been published in more than forty-five countries, is the author of more than fifty books of fiction, poetry, critical essays, and graphic novels. In addition to The Handmaid’s Tale, now an award-winning TV series, her novels include Cat’s Eye, short-listed for the 1989 Booker Prize; Alias Grace, which won the Giller Prize in Canada and the Premio Mondello in Italy; The Blind Assassin, winner of the 2000 Booker Prize; The MaddAddam Trilogy; The Heart Goes Last; and Hag-Seed. She is the recipient of numerous awards, including the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade, the Franz Kafka International Literary Prize, the PEN Center USA Lifetime Achievement Award, and the Los Angeles Times Innovator’s Award. In 2019 she was made a member of the Order of the Companions of Honour in Great Britain for services to literature and her novel The Testaments won the Booker Prize and was longlisted for The Giller Prize. She lives in Toronto.