When I was nine, I was a very good girl; I hadn’t always been. In my early childhood, the tyranny of adults threw me into such raging fits that one day, one of my aunts seriously declared: “Sylvie is possessed by demons.” War and religion had defeated me. I immediately proved my exemplary patriotism by stomping on a plastic doll that was “made in Germany”; I didn’t like it anyway. I was taught that my good behavior and piousness would determine whether God saved France: I couldn’t escape. I walked through the Basilica of Sacré Coeur with the other little girls, waving banners and singing. I started praying a very great deal and grew to like it. Father Dominique, who was the chaplain at Adélaïde, my school, encouraged my devotion. Wearing a tulle dress and a bonnet made of Irish lace, I took my First Communion: from that day onward, I was held up as an example to my younger sisters. My prayers were answered when my father was transferred to the War Ministry due to a heart condition.

On that particular morning, however, I was very excited; it was the first day of school. I was eager to get back: the classes (as solemn as a church Mass), the silence of the corridors, the sweet smiles of the young ladies. They wore long skirts and high-necked blouses, and since a part of the building had been transformed into a hospital, they often dressed as nurses. Beneath their white veils stained here and there with blood, they looked like saints, and I was moved when they pressed me to their hearts. I quickly wolfed down the soup and tasteless bread that had replaced the hot chocolate and brioche we’d had before the war, and waited impatiently as Mama finished dressing my sisters. All three of us had on sky blue coats made of the same fabric that the officers wore and tailored exactly like military greatcoats.

“Look, there’s even a little belt!” said Mama to her admiring or amazed friends. As we left the building, Mama held hands with the two little ones. We sadly passed the Café de la Rotonde that had noisily opened below our apartment and which was, said Papa, a hideout for defeatists; the word intrigued me. “They are the people who believe in the defeat of France,” Papa explained. “We should shoot them all.” I didn’t understand. You don’t believe what you believe on purpose: could you be punished because certain ideas come into your mind? The spies who gave poisoned candy to children, or the ones who stabbed French women with poisoned needles, obviously deserved to die, but the defeatists left me perplexed. I didn’t try to ask Mama: she always gave the same answers as Papa.

My little sisters did not walk quickly; the gates of the Luxembourg Gardens seemed to go on forever. Finally, I got to school, climbing up the stairs and happily swinging my schoolbag full of new books. I recognized the faint odor of sick patients mixed in with the smell of floor wax in the freshly polished hallways; the supervisors hugged me. In the coatroom, I saw my friends from the year before; I wasn’t close with anyone in particular, but I liked the noise we made all together. I stood for a while in the large auditorium, in front of the display cases full of old dead things that managed to die a second time: stuffed birds lost their feathers, dried plants crumbled, shells faded. The bell rang and I went into the Sainte Marguerite classroom; all the classrooms were the same. The pupils sat around an oval table covered in black moleskin and were supervised by the teacher. Our mothers sat behind us, watching us as they knitted balaclavas. I headed to my seat and saw that the one next to mine was taken by a little girl I didn’t know; she had brown hair and hollow cheeks and looked much younger than I was. Her dark, shining eyes stared at me intensely.

“Are you the best pupil?”

“I’m Sylvie Lepage,” I said. “What’s your name?” “Andrée Gallard. I’m nine; if I look younger, it’s because I was burnt to a crisp and didn’t grow much. I couldn’t go to school for a year, but Mama wants me to catch up. Could you lend me your notebooks from last year?”

“Yes,” I said. Andrée’s confidence and her precise, rapid way of speaking unsettled me. She looked me up and down defiantly.

“The girl next to me said you were the best pupil,” she said, nodding slightly toward Lisette. “Is it true?”

“I’m often at the top of the class,” I said somewhat shyly.

I stared at Andrée; her dark hair fell straight down around her face, and she had an ink stain on her chin. You don’t meet a little girl who was burned alive every day, so I wanted to ask her a lot of questions, but Mademoiselle Dubois had come in, her long dress sweeping across the floor. She was a brisk woman who had a mustache and whom I respected a lot. She sat down and called out our names; she looked up at Andrée: “Well, my dear, we don’t feel too intimidated, do we?”

“I’m not shy, Mademoiselle,” said Andrée confidently. “Besides,” she added pleasantly, “you’re not intimidating.”

Mademoiselle Dubois hesitated for a moment, then smiled beneath her mustache and continued taking attendance.

The end of classes finished with the usual ritual: Mademoiselle stood at the doorstep, shook the hand of each mother, and kissed every child on the forehead. She placed her hand on Andrée’s shoulder: “You’ve never been to school?”

“No; until now I’ve worked at home, but now I’m too big.”

“I hope you’ll follow in your older sister’s footsteps,” said Mademoiselle.

“Oh! We’re very different,” said Andrée. “Malou takes after Papa, she loves math, but I especially love literature.” Lisette poked me with her elbow. You couldn’t say that Andrée was impertinent, but she didn’t use the tone of voice she should have when talking to a teacher.

“Do you know where the study room is for day students? If no one comes to pick you up right away, that’s where you should go and wait,” said Mademoiselle.

“No one is coming to pick me up; I’m going home by myself,” said Andrée, then quickly added, “Mama told the school.”

“By yourself?” asked Mademoiselle Dubois; Andrée shrugged. “Well, if your mother told the school . . .”

Mademoiselle Dubois kissed me on the forehead when it was my turn, and I followed Andrée into the coatroom. She slipped on her coat: it was not as unique as mine, but it was very pretty, made of thick wool, red with gold buttons. She wasn’t a street urchin, so why was she allowed to go out alone? Wasn’t her mother aware of the danger of deadly candy and poisoned needles?

“Where do you live, Andrée dear?” asked Mama as we were going down the stairs with my little sisters.

“Rue de Grenelle.”

“Oh, well, then! We’ll walk with you to the Boulevard Saint-Germain,” said Mama. “It’s on our way.”

“With pleasure,” said Andrée, “but please don’t go out of your way for me.” She looked at Mama. “You see, Madame,” she said quite seriously, “there are seven of us children; Mama says that we have to learn how to manage by ourselves.”

Mama nodded, but it was obvious she didn’t approve. As soon as we were out on the street, I questioned Andrée: “How did you get burned?”

“I was cooking some potatoes over a campfire; my dress caught fire, and my right thigh was burned right down to the bone.” Andrée made a small gesture of impatience; this old story bored her. “When can I see your notebooks? I need to know what you studied last year. Tell me where you live, and I’ll come by this afternoon or tomorrow.”

I looked at Mama for approval; I wasn’t allowed to play with children I didn’t know in the Luxembourg Gardens.

“This week isn’t possible,” said Mama, sounding embarrassed. “Maybe on Saturday; we’ll see.”

“All right; I’ll wait until Saturday,” said Andrée.

I watched her cross the wide boulevard in her red woolen coat; she was really very small, but she walked with the confidence of an adult.

“Your uncle Jacques knew the Gallards, who were related to the Lavergnes, the Blanchards’ cousins,” Mama said in a dreamy voice. “I wonder if it’s the same family. But it seems to me that respectable people would not allow a little child of nine to run around the streets alone.”

My parents discussed the various branches of the Gallard families for a long time, what they’d heard from people close to them or from third parties. Mama got information from the teachers. Andrée’s parents were only distantly related to Uncle Jacques’s Gallards, but they were very highly regarded. Monsieur Gallard had attended the Polytechnique, held an excellent post at Citroën, and was the chairman of the League of Fathers of Large Families. His wife, née Rivière de Bonneuil, belonged to a large dynasty of militant Catholics and was well respected by the parishioners of Saint Thomas Aquinas. Informed, most likely, of my mother’s concerns, Madame Gallard came to pick up Andrée the following Saturday at the end of the school day. She was a beautiful woman with dark eyes who wore a black velvet ribbon around her neck; it was held in place by an antique pin. She won Mama over by telling her that she looked young enough to be my older sister and by calling her “young lady.” But I didn’t like her velvet necklace.

Madame Gallard had indulgently told Mama the story of Andrée’s martyrdom: the cracked skin, enormous blisters, paraffin-coated dressings, Andrée’s delirium, her courage, how one of her little friends had kicked her while they were playing a game and had reopened her wounds. She’d made such an effort not to scream that she’d fainted. When she came to my house to see my notebooks, I looked at her with respect; she took notes in beautiful handwriting, and I thought about her swollen thigh under her pleated skirt. Never had anything as interesting happened to me. I suddenly had the impression that nothing had ever happened to me at all.

All the children I knew bored me, but Andrée made me laugh when we walked together on the playground between classes. She was marvelous at imitating the brusque gestures of Mademoiselle Dubois, the unctuous voice of Mademoiselle Vendroux, the principal. She knew loads of secrets about the place from her older sister: these young women were affiliated with the Jesuits; they wore their hair parted on the side when they were still novices, in the middle once they’d taken their vows. Mademoiselle Dubois, who was only thirty, was the youngest. She’d taken her baccalaureate the year before; the older students had seen her at the Sorbonne, blushing and all awkward in her long skirt. I was a little scandalized by Andrée’s irreverence, but I found her funny, and played opposite her when she improvised a dialogue between two of our teachers. Her caricatures were so accurate that we often poked each other with our elbows during lessons when we saw Mademoiselle Dubois open the attendance register or close a book. Once I was so overcome with laughter that I surely would have been thrown out of the class if my behavior hadn’t normally been so exemplary.

The first few times I went to play at Andrée’s house on the Rue de Grenelle, I was dumbfounded. Apart from her brothers and sisters, there were always masses of cousins and friends; they ran, shouted, sang, dressed up, jumped on the tables, overturned the furniture. Sometimes Malou, who was fifteen and bossy, intervened, but then you’d immediately hear Madame Gallard’s voice saying, “Let the children have fun.” I was astounded by her indifference to the injuries, bumps, stains, broken dishes. “Mama never gets angry,” Andrée said to me with a triumphant smile. At the end of the afternoon, Madame Gallard came into the room we’d wrecked, smiling; she picked up a chair and dried Andrée’s forehead, saying, “You’re drenched in sweat again!” Andrée hugged her tightly, and for an instant, her face was transformed. I looked away, feeling uneasy, probably because I was a little jealous, perhaps envious, and I felt the kind of fear aroused by the unknown.

I had been taught that I had to love Mama and Papa equally: Andrée didn’t hide the fact that she loved her mother more than her father. “Papa is too serious,” she calmly said to me one day. Monsieur Gallard puzzled me because he wasn’t like Papa. My father never went to Mass, and he smiled whenever someone talked about the miracles of Lourdes in front of him; I’d heard him say that he had only one religion: the love of France. I was not troubled by his irreverence. Mama, who was very pious, seemed to find it normal; a man as superior as Papa necessarily had a more complicated relationship with God than women or little girls did. Monsieur Gallard, on the other hand, took Communion every Sunday with his family; he had a long beard, wore a pince-nez, and volunteered to do good works in his spare time. His silky hair, his Christian virtues, made him seem feminine and belittled him in my eyes. Anyway, he was seen only under unusual circumstances. It was Madame Gallard who ruled the house. I envied the freedom she gave to Andrée, but even though she always spoke to me most kindly, I felt uncomfortable with her.

Sometimes Andrée would say: “I’m tired of playing.” We’d go and sit down in Monsieur Gallard’s office and not turn on the lights so we wouldn’t be discovered, and then we’d chat: it was a new pleasure. My parents talked to me and I talked to them, but we never chatted together; with Andrée, I had real conversations, like Papa did in the evening with Mama. She’d read a lot of books during her long convalescence, and she surprised me because she seemed to believe that the stories the books told had actually happened: she detested Corneille’s Horace and Polyeucte, admired Don Quixote and Cyrano de Bergerac as if they had existed in flesh and blood. Where earlier centuries were concerned, she also had her favorites. She liked the Greeks, but the Romans bored her; though unmoved by the misfortunes of Louis XVII and his family, she was devastated by the death of Napoleon.

Many of these opinions were subversive, but given her young age, the novices forgave her. “That child has personality,” they said at school. Andrée quickly caught up; I only barely beat her in composition, and she had the honor of copying two of her essays into the special book used to display excellent work. She played the piano so well that she was immediately placed in the intermediate group; she also started taking violin lessons. She didn’t like to sew, but she was good at it; she competently made caramels, shortbread cookies, chocolate truffles. Even though she was frail, she knew how to turn cartwheels, could do the splits and all sorts of somersaults. But what gave her the greatest prestige in my eyes were certain unique characteristics whose meanings I have never understood: when she looked at a peach or an orchid, or if anyone simply said either word in front of her, Andrée would shudder, and her arms would break out in goose bumps; those were the times when the heavenly gift she’d received—and which I marveled at so much—would manifest itself in the most disconcerting way: it was character. I secretly told myself that Andrée was one of those child prodigies whose lives would later be recounted in books.

_______________________________________

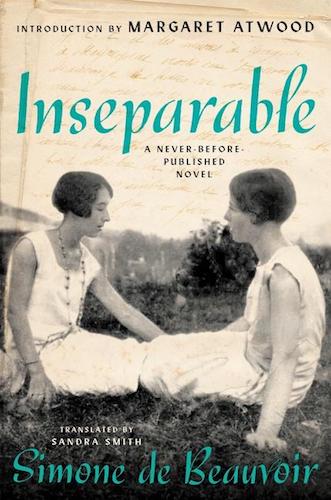

From Inseparable by Simone de Beauvoir. Copyright © 2021 by Éditions de L’Herne. English translation copyright © 2021 by Sandra Smith. Excerpted by permission of Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.