Margaret the First, a Novel and an Obsession

In Conversation with Danielle Dutton on Saying Goodbye to Mad Madge

Margaret the First (Catapult) is Danielle Dutton’s third novel and continues, albeit more gently, in the experimental vein she tapped for her first two: Attempts at a Life (Tarpaulin Press) and S P R A W L (Siglio).

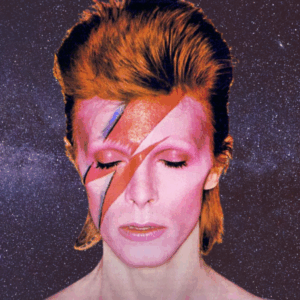

However, as I type these lines, it is not Dutton’s stylish, exuberant prose I’m studying, but the enigmatic and magnetic figure in the cover painting. Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle and 17th-century Englishwoman who earned the moniker “Mad Madge,” stares out at the reader through clear amber eyes and issues a dare.

While the painting, commissioned by Catapult from artist June Glasson for the book, is terrific (more on Dutton’s reaction to it in a moment), I’m drawn to it because I’ve read the book and wish fiercely that I could meet its subject. Cavendish, due to factors including her inherent curiosity and intellect as well as her privileged marriage and societal position, carved out an identity as a writer, poet, and woman of ideas in 17th-century England—a time not known for its feminist bent.

While Dutton, who founded Dorothy, a Publishing Project with her husband Martin Riker, does have a feminist bent, and a strong one, reading her work and listening to her speak reminds me of something Margaret Cavendish would understand: Minds ablaze with interest and passion are sexless, genderless, filled with wonder. That’s the quality captured by Glasson in her cover painting. “Come meet me as a person,” this version of Cavendish seems to say.

Bethanne Patrick: How did you discover Margaret Cavendish?

Danielle Dutton: Truly through Virginia Woolf; when I was completing my PhD in English—which was actually in creative writing—I had a period of intense interest in British modernism. Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own was where I first saw Margaret’s name. The 17th century, I learned, was a very anti-systematic period and a very hybrid period. A man could be a poet and a scientist and an ambassador, all at once, or in one lifetime.

Margaret fascinated me from the beginning, and as I read more and more about the era, it just kept shifting, for me, to be more and more about Margaret. Woolf’s essay in The Common Reader titled “The Duchess of Newcastle” is amazing, because Woolf seems sympathetic and wanting to like Margaret, but she also criticizes her harshly. I have the advantage of feminism having happened, and feminists can reclaim Margaret Cavendish. I decided I wanted to find Margaret for myself.

BP: Did Woolf influence you, however?

DD: Woolf just never left. She was there at the very beginning, and the more I wrote the book the more I found myself turning to Woolf’s own writing. The rhythms of her language really helped me. Woolf infuses this book.

Part of what inspired me in this period is its wonder and beauty; I feel a lot of that in Woolf’s prose, too—she sort of paints with words. I wanted people to have that feeling from my book. How does Woolf talk about a tree? Her prose is so lyrical without being just poetry. It feels like there’s a narrative, but that the language is poetic.

BP: Speaking of “wonder and beauty,” your book’s cover has both.

DD: I did not work on cover—that was the fantastic work of Catapult’s book designers and painter June Glasson. What was remarkable is that the dress the “cover Margaret” wears is one I had written, I had imagined. I made something up and a painter figured out what it actually looked like. I freaked out when I saw it—I loved it. It was like a birthday and Christmas and Hanukkah all rolled into one.

I was nervous about having Margaret on the cover, I felt it might limit the reader. Never did I dream they would commission a new one. You can’t look away from that cover image’s face. She’s looking right at you, the reader, but: Is she smiling? Is she scared? Is she dreaming up something radical? It’s just right, somehow.

BP: You’ve talking about painting with words, and the painting on your cover. Does visual art mean something to you?

DD: Well, I’ve always responded to visual art in my writing. I went to a visual arts school for my MFA. My understanding of contemporary writing is completely shaped by being in art school. When I went to work in a British Waterstones bookstore after college, where I studied medieval art and history, I was completely confused by this thing called “the frontlist.” I’d never realized that there were modern, working writers, that this was a thing you could actually do in life.

BP: You lived in England for a while, as you just noted. That’s interesting, because a great deal of “Margaret the First” is infused with imagery of the British countryside.

DD: Most of the time I was there was spent in the North, in Sheffield. I love England! I haven’t been back in a long time, but I’ve always felt good in England. Part of it is the literary imagination I have of England that’s mixed in with my memories.

However, I think one of the reasons there’s so much about the natural world in this book is because the shift from the medieval to the modern fascinates me. I loved that Margaret was alive in that moment, that she got to meet and talk with so many.

BP: That must have affected how you wrote about her; can you talk about that?

DD: I started writing Margaret during the time she first came to her much-older husband’s estate, Welbeck. She’d just finished her book The Blazing World and I wrote in intense, super-close, third person. She had become a whole woman to me through my readings on her and I wanted to look at her whole entire story.

However, then I had to figure out how that worked. I didn’t want to simplify or romanticize her. I wanted a complicated portrait of a complicated person. I had to pull back and think who would this person have been as a child? It was a process of finding her voice in childhood and making that bridge to the historical “Madge,” as she was later known.

I never tried to make her contemporary. Being a creative person has this sort of universality, but I struggled with how to show that without giving her a creative process that would make no sense to her. There is some material about what she thought of her own work, and there are some historical realities I couldn’t overlook: For example, she would have written with a quill. However, I did want to show her writing alone, which may or may not have been possible much of the time.

BP: After all, she was married, and her husband William was one of her greatest supporters.

DD: Creating the marriage was a big part of the book. I started the novel over a decade ago, right when I was getting married, and the more I was married, the more important marriage seemed. I do have a very functional and good marriage, and I do not know if I could do everything I do as an artist if I did not have a supportive spouse. Even in a good and happy and working marriage there are times when you’re not in synch, times when you’re much closer, times when someone just plain snaps! That’s real, that’s what marriage is like. It seems clear to me that Margaret wouldn’t be the person we study and think about if she hadn’t been married to William. Not only was he incredibly supportive of her writing—his position threw her into a conversation that she quickly became a part of herself.

BP: Another aspect of Margaret Cavendish that we must touch on is her ambition. She wanted to be heard. She wanted to be acknowledged as part of that conversation.

DD: I think Margaret had a sort of deep fear of death and oblivion. She wanted to matter, to never be forgotten, to live forever in many brains, but it wasn’t simply for the sake of fame itself. She wanted to matter! She saw all these ways around her of mattering, but not for women. She sort of pushed her way in to this masculine space. She was totally radical and remarkable. She could be hard on women in the way that Woolf was hard on her. She believed that women should be educated and speak and listened to. She was blazing trails! It’s just so shocking that she’s not more widely known. I was writing this because I was totally fascinated by her. I couldn’t let it go. How is it possible that I’ve never heard of this person? Bacon, Hooke, etc. but no Margaret Cavendish!

When I was finishing the book I was hoping in this weird little ghostly way that she’d know she was going into more brains. The more it got read.

BP: You’re so passionate about Margaret that I have to ask you what is was like to let her go.

DD: It was really hard to come to the end! When I was done I was sort of depressed for a few months afterward. I didn’ t know who I was supposed to be if I wasn’t writing that book. Being part of Margaret had become who I was as a writer for many years. It is really amazing to see people’s interest in Cavendish, that people are so excited to learn about her. For those months in between I was just sad.

Part of that sadness may have stemmed from my realization that she never got to the biggest freedom, inside of herself. She died somewhat suddenly; there wasn’t anything for me to overlook or to spin further. Nature is such a big part of this book that it just seemed right I should have her die alone in a garden chair. I finished her.

BP: What comes next, then?

DD: My own pattern of writing has been that one book is not at all like the next. That really pleases me. The next book will not be historical fiction, although what it will be remains to be seen. The key seems to be finding a language that I want to spend some time with. Something has to start to fascinate me; once I become fascinated, the language is not hard to find.

Bethanne Patrick

Bethanne Patrick is a literary journalist and Literary Hub contributing editor.