Famous Literary Relationships from Best to Worst

This valentine's day, why not judge yourself against your favorite writerly romance?

The feast of St. Valentine is upon us yet again—I hope you’ve made the proper arrangements to show your beloved that you care (even if that means not actually marking the holiday at all; this really depends on your beloved.) Perhaps you will look to the literary world for inspiration, since after all, there have been plenty of great legends about literary love affairs over the years, though of course a great legend doesn’t always mean a great love affair. In fact, it often means just the opposite. Here, I’ve collected a few of the worst (and a few of the best)—from what we can tell from our outside vantage, at any rate. You never do know what goes on in other people’s homes. But you might have a better chance if they happen to be writers.

NB: I’ve left out many people here, because lists are necessarily finite, but I’ve pointedly discounted all of the current contemporary literary couples on the basis that I have no historical basis for judging them—but if I were going to judge them, based on, let’s say, their skill in writing and general attractiveness, there would be several more “bests.” (Zadie Smith & Nick Laird, Valeria Luiselli & Álvaro Enrigue, Katie Kitamura & Hari Kunzru, etc, etc. Happy Valentine’s Day to them, too!)

Virginia Woolf & Leonard Woolf & Vita Sackville-West

Leonard had to propose three times to Virginia; at first she wasn’t sure if she was sexually attracted to him. Actually, at first she was sure she wasn’t; but that ultimately changed. When she finally accepted his offer, she wrote to a friend: “My Violet, I’ve got a confession to make. I’m going to marry Leonard Woolf. He’s a penniless Jew. I’m more happy than anyone ever said was possible—but I insist upon your liking him too. May we both come on Tuesday?” The two began a loving, mutually supportive relationship, both personal and professional—they founded the Hogarth Press together. In 1937, Virginia wrote in her diary, “Love-making—after 25 years can’t bear to be separate… you see it is enormous pleasure being wanted: a wife. And our marriage so complete.”

As far as the famous Vita is concerned, she and Virginia met in 1922 and began an affair (Leonard knew all about this, and so did Vita’s husband, and everyone was fine with it; they were modernists, after all), writing gorgeous love letters to one another, the most accomplished of which, of course, is Woolf’s Orlando, about which Sackville-West’s son later wrote, “The effect of Vita on Virginia is all contained in Orlando, the longest and most charming love letter in literature, in which she explores Vita, weaves her in and out of the centuries, tosses her from one sex to the other, plays with her, dresses her in furs, lace and emeralds, teases her, flirts with her, drops a veil of mist around her.” The affair lasted until 1929, and the two remained close until Woolf’s death. But in the end, it was Leonard to whom Virginia addressed her last letter, one that attests to the happiness they shared:

Dearest,

I feel certain that I am going mad again. I feel we can’t go through another of those terrible times. And I shan’t recover this time. I begin to hear voices, and I can’t concentrate. So I am doing what seems the best thing to do. You have given me the greatest possible happiness. You have been in every way all that anyone could be. I don’t think two people could have been happier ’til this terrible disease came. I can’t fight any longer. I know that I am spoiling your life, that without me you could work. And you will I know. You see I can’t even write this properly. I can’t read. What I want to say is I owe all the happiness of my life to you. You have been entirely patient with me and incredibly good. I want to say that—everybody knows it. If anybody could have saved me it would have been you. Everything has gone from me but the certainty of your goodness. I can’t go on spoiling your life any longer.

I don’t think two people could have been happier than we have been. V.

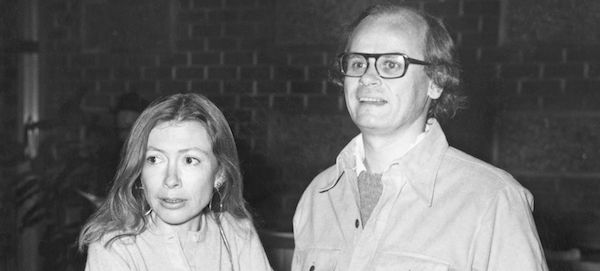

Joan Didion & John Gregory Dunne

Didion and Dunne met in the late 1950s, while they were both working for magazines—she at Vogue, he at Time. “We amused each other and I thought he was smart,” Didion later said in an interview. “He knew a lot of stuff that I didn’t know, like politics and history—I had managed to go through school without learning much except a lot of poems.” They married in 1964 and adopted a daughter in 1966; by all accounts, they built one another up, they shared work and love. In a 1987 profile of the pair, Leslie Garis described their partnership and home this way:

In fact, entering the Dunnes’ house after reading their work is like finding an opposite universe. There is, primarily, a rooted, secure sense of family. Everywhere are photographs of their daughter, Quintana Roo, a 20-year-old junior at Barnard.

This is a settled, peaceful home, furnished with a developed eye and family heirlooms, such as the Chickering piano that has been in Didion’s family for generations. On tables are groupings of cut-glass bowls, vases, little china cups and a particularly striking collection of hurricane lamps, scattered about the gleaming surfaces as if anticipating disaster.

…

“I do remember that time,” Dunne says, entering the room without missing a beat, “when you wrote, ‘We are here on this island in the middle of the Pacific in lieu of filing for divorce.’ And we flew from Hawaii to New York. The piece appeared the day before we arrived. We went to a party at Esquire and people were surprised that we walked in together.”

“I kept saying to everybody ‘In lieu of divorce! In lieu of!'” They laugh uproariously. As the critic Digby Diehl said about them, “For depressed people they certainly laugh a lot.”

In 2003, when Quintana Roo was sick in the ICU, Dunne suffered a fatal heart attack. Less than two years later, Quintana Roo died as well. In 2005, Didion published The Year of Magical Thinking, a beautiful book about Dunne’s death and her grief, which won the National Book Award for Nonfiction; in 2011, she published Blue Nights, which grapples with her daughter’s death.

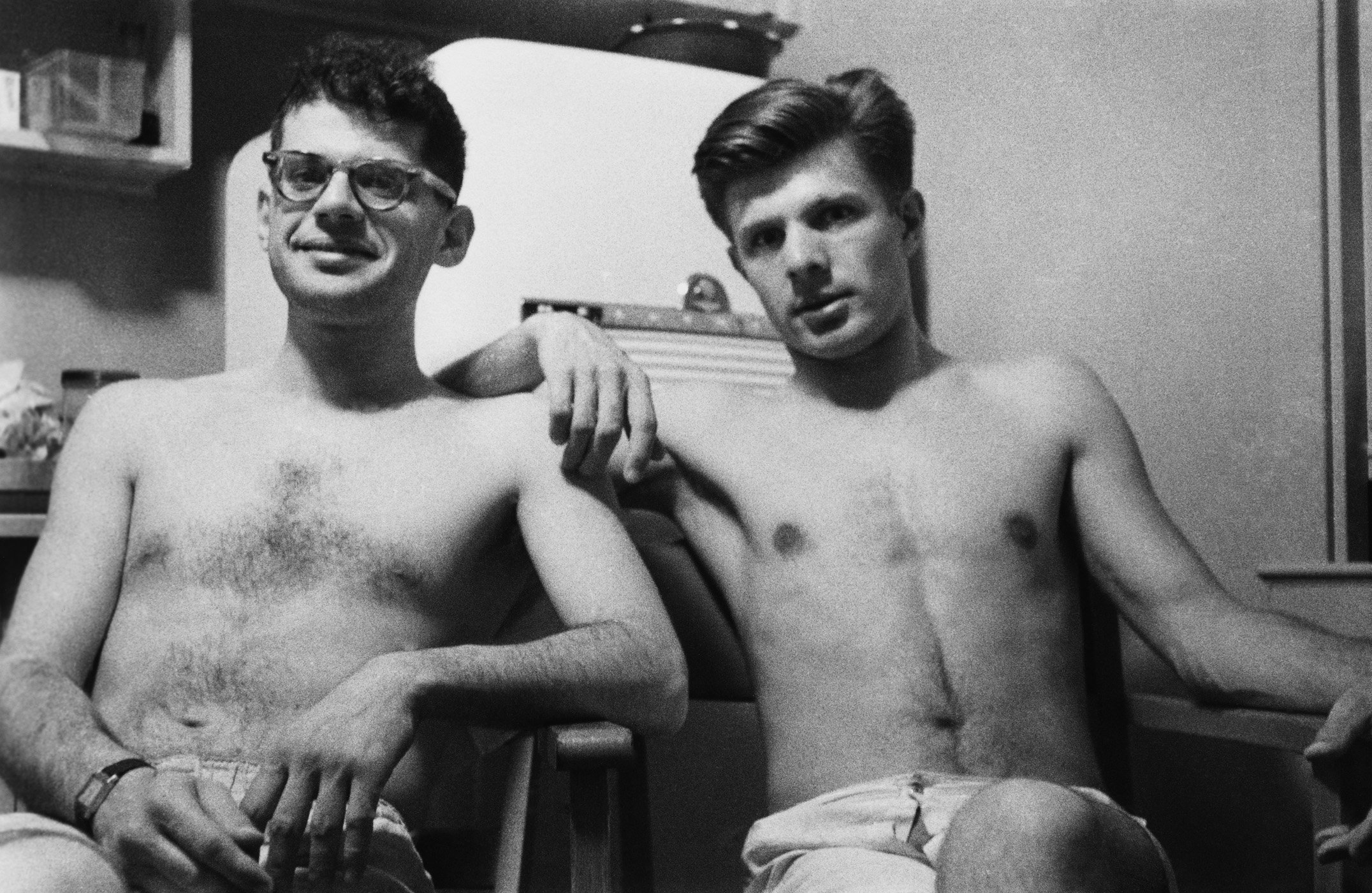

Allen Ginsberg & Peter Orlovsky

I love looking at the progression of years in the many photographs of Ginsberg and Orlovsky—who met in 1954 and stayed together until Ginsberg’s death in 1997—you see them aging together, bit by bit, but the best part is that they always seem to be having such luxurious fun—their life was clearly filled with joy. Despite the times, they referred to their relationship as a marriage, though the exact nature of the relationship fluctuated over the years, and they both slept with other people. A number of their love letters survive: they are childish, in that Beat poet way, but lovely. “Life seems emptier without you,” Ginsberg writes in one of these, “the soulwarmth isn’t around…”

Simone de Beauvoir & Jean-Paul Sartre

It shouldn’t be surprising that the leading intellectual couple of the 20th century had an unusual relationship—though, actually, it isn’t even that unusual. Just an open relationship, if one that was a little more lurid than Ginsberg and Orlovsky’s. As Louis Menand reports, de Beauvoir and Sartre had a pact: they could sleep with whomever else they wished, so long as they told one another everything. “The comradeship that welded our lives together made a superfluous mockery of any other bond we might have forged for ourselves,” de Beauvoir wrote. “At times this meant that we had to follow diverse paths—though without concealing even the least of our discoveries from one another. When we were together we bent our wills so firmly to the requirements of this common task that even at the moment of parting we still thought as one. That which bound us freed us; and in this freedom we found ourselves bound as closely as possible.” From Menand’s account, the two had a distinctly Cruel Intentions vibe—they indeed told each other everything, which amounted to a lot of voyeuristic shit-talking behind their other lovers’ unsuspecting backs. Apparently, de Beauvoir would even sometimes romance her young female students and then “pass them on” to Sartre, in a move they called the “trio.” She was eventually fired for this, and even lost her license to teach in France.

Ernest Hemingway & Martha Gellhorn

Like many relationships, things in this famous literary marriage started off great. They fell in love. They gave each other nicknames. Hemingway encouraged Gellhorn’s journalistic writing. They were happy. But then, as Caroline Moorehead, Gellhorn’s biographer, put it:

In so much as ends have beginnings, theirs came in the summer of 1943. Hemingway was drinking heavily and she found his lack of cleanliness, his boundless egotism and his crassness increasingly offensive; he accused her of being a prude and a prima donna. There was little laughter and few jokes.

One night, when he was drunk, she took over the wheel of his much loved Lincoln Continental. He slapped her; she drove it slowly and deliberately into a tree. They fought over money, over work, over his drunken cronies. He bullied, mocked and snarled at her. Then the day came when he told her that he had accepted a commission to cover the Allied invasion for Collier’s—effectively demoting her, since no paper could have more than one reporter at the front. There was little more to be said. Hemingway left for London on a priority flight; Gellhorn crossed the Atlantic on a Norwegian freighter carrying dynamite.

Later, Gellhorn would refuse to talk about Hemingway in any interviews, and reportedly didn’t even like to discuss him with friends. She didn’t want, she said, to become “a footnote in someone else’s life.” She wanted only to do her work.

Robert Lowell & Jean Stafford & Elizabeth Hardwick & Caroline Blackwood

Robert Lowell was, at various points, married to three notable female writers: first Jean Stafford (he got the two of them into a car accident that left her permanently disfigured, though of course he was fine); their relationship itself seems to have been equally bumpy. Then Elizabeth Hardwick, with whom he had a daughter. Of their relationship, Michelle Dean writes:

Though they were married for 23 years, their union was worn down by Lowell’s nearly annual hospitalizations for manic depression, his endless philandering, and his alcoholism. At the end of it, almost on a whim, he left her for the writer and “muse”—always a loaded term, that—Lady Caroline Blackwood. Then he took Hardwick’s alternately furious and anguished letters to him and folded them, without her consent, into a full-length book of poetry, The Dolphin. This artifact of her humiliation won a Pulitzer. Yet Hardwick still continued to try to get him back, right up to the day of his death.

Supposedly, it almost worked. As the story goes, in 1977 Lowell finally left Blackwood, hopped in the back of a cab to Hardwick’s apartment, but died of a heart attack on the way there, clutching a painting of Blackwood. Talk about your mixed messages.

Paul Verlaine & Arthur Rimbaud

This intense, absinthe-fueled affair—for which Verlaine abandoned his wife and son—ended with Verlaine luring Rimbaud to a hotel and shooting him. Well, in the wrist. Love makes you aim badly, it seems. Or at least love when it’s accompanied by large amounts of alcohol and hash. Poets, man.

Sylvia Plath & Ted Hughes

Plath’s fans hate Ted Hughes so much that they continually go to her grave and chip off the “Hughes” at the end of her name. Why? Well, he cheated on her, and after her death burned her journals, and sought to otherwise obscure her legacy in order (some say) to keep himself from looking bad. It’s not fair to say definitively that Plath’s suicide had anything to do with Hughes’s treatment of her—she was clearly clinically depressed—but lots of people still connect the two, and at our vantage, it’s hard to say. We do know that in 1962, Hughes began an affair with Assia Wevill, who was subletting the Hughes’s flat (with her husband), and reportedly the affair (and subsequent pregnancy, which was terminated) was the reason for Ted and Sylvia’s separation that fall. A few months later, Sylvia Plath committed suicide. Only a few years after that, Wevill—to whom Hughes was not faithful either—killed herself, and the daughter she had with Hughes, in almost exactly the same way (sleeping pills, oven gas). It’s hard not to see the common denominator there.

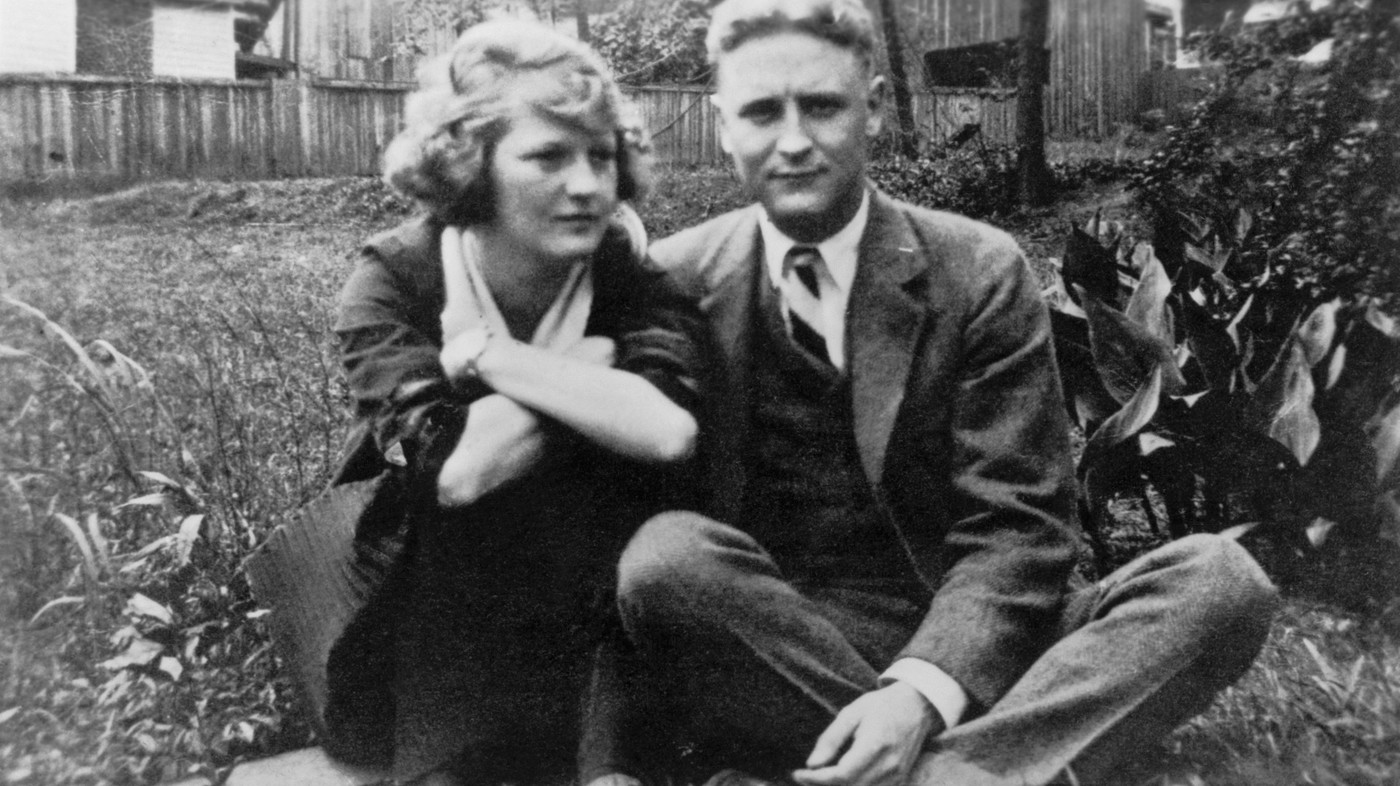

Zelda Fitzgerald & F. Scott Fitzgerald

The Fitzgeralds are famous for being literary lushes—and also for having a terrible relationship. All that partying led to intense fighting, cheating, and violence. Plus, F. Scott famously stole wholesale from Zelda’s diaries and looked down on her own literary aspirations. When F. Scott died, he was living in Hollywood with his mistress, a gossip columnist named Sheilah Graham, and Zelda was living in a mental hospital in North Carolina, into which her husband had committed her a few years before. Since he wasn’t considered Catholic enough to be buried in his family plot, Zelda bought him a space in Rockville Cemetery, in Maryland. She didn’t attend the funeral, but when she died eight years later—when the hospital he’d stashed her in burned down—she was buried with him. She was not buried next to him, mind. Zelda only bought one plot, so her casket sits directly on top of his, a fitting final fuck-you.

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.