I am a Camp Cot, Folding. My NSN is 7105-99-383. I was one of the first to arrive at the base. They unloaded me from an ISO container and threw me in a pile with all the others. Around us, an excavator was filling protective walls with rubble and helmeted men erected antennas by a command post. A watchtower was being constructed on top of an old building.

The camp expanded and a line of tents sprouted along a wall as more men arrived. When helicopters landed, the world turned brown and a thin layer of dust collected on me. The new men were issued kit from the piles and I was picked up and carried to a small room cut into the wall of an old courtyard. A man unfolded me and my canvas stretched taut on my aluminum frame. He attached a dome that held a mosquito net to my four corners. This was the first man I ever supported.

I was used as a goal. I was blown over by the downdraught of helicopters. My legs sank into the mud when the rains came.

After a few months he left and another man replaced him. This one stayed longer. During the months he slept on me, he became lighter and his skin more deeply tanned. Time dragged for him and nerves kept him awake towards the end, when he was so close yet couldn’t imagine being safe.

The next man landed in a helicopter, came into the room and dumped his kit beside me. Then the camp was attacked and he ran out to help. Like the others, his days followed a pattern of shifts, meals and attacks. He pulled on his heavy body armor, day-sack and helmet, and walked out with his rifle and was gone for hours. When he came back he was hot and elated or exhausted.

Men nudged him in the night and told him it was his turn to man the ops room. He would sit up on me and push his feet into flip-flops, sigh and walk across the dark courtyard.

He sometimes slept on me during the day, when it was so hot he sweated the shape of his body into my canvas. After he woke, he wrapped a green towel around his waist, filled a red tub and stood in it, pouring water over his head with a mess tin.

When it became even hotter and the room was an oven, he dragged me out into the courtyard and slept under the stars. Sometimes he couldn’t sleep and hooked earphones in and looked up through the gauze netting at the sky.

There was another bed like me in the room. His friend slept in that one. When their shifts overlapped, they chatted and laughed, read their post to each other and shared food from parcels. Once he returned and two camel spiders had been dropped on top of me and were crawling over his sleeping bag. He told his friend how funny he was and said he’d get him back.

In the room around me, cardboard boxes were stacked and ripped open. The men delved into them and chose foil packets they took away to eat.

He sat on me and stripped his rifle down to clean it and the gas parts left oil marks on me. He checked and replenished his ammunition. Sometimes he zipped the net closed to make me his private space. He lay on his sleeping bag with a head torch on and read a book.

One night, after he had been busy all day and his skin was grimy and he was too exhausted to wash, he removed his combat boots and socks and let his white feet expand and cool on me. He thought about the patrol he’d just finished as he looked up at the endless stars.

He wondered if his men could have outflanked them and he relived pulling the trigger and the puffs as his rounds had slammed into the compound in the distance. The sound of metal travelling through the air filled his head again: the fizzing of ricochets; everyone gasping for breath after he’d sprinted and thrown himself into cover.

He thought about what he’d said on the radio, how he’d commanded his platoon, how he’d described the situation to Zero. He could still hear his men’s shouts amidst all the confusion. He remembered crouching in the ditch and trying to work out what was happening, trying to piece the battle together. The enemy had disappeared. He should have followed and caught them but he chose to be cautious since air support was on its way.

He put his hands under his head and against me. There was still dirt between his fingers.

He couldn’t stop it all going around in his head. It had been a chance to be bold, to close and kill—but they’d disappeared into the fields and trees among the confusing compounds. He imag- ined himself being brave among the tight walls and neutralizing them at close quarters, leading his men relentlessly forward.

He thought of the jet flying over and the thrill as it disintegrated the wall and one of his men whooping from along the ditch. He replayed everything as he should have fought it, decisively and without hesitation. He promised himself that next time he would.

And then these thoughts merged into details of tomorrow’s mission. And he was back out in the network of fields, moving between other houses and locals, and he tried to decide how best he should clear the area. He had so little time to prepare; he’d have to give orders early and his men were exhausted already. He was overwhelmed by it and he reached for his alarm clock to set it an hour earlier. And then he remembered another thing he should tell them about the mission and the planning went on and on in his head.

And as often happened with the men that slept on me, he remembered a place far away that didn’t involve any of this. He was sitting on the lawn at his parents’ house in the cool sunlight, and the dog was trying to lick him as he laughed and played with it.

Then he was heading into town and he thought of a girl. She wasn’t right for him, but somehow, out here, she seemed to be. And he recalled other girls, some that he’d only glanced at, or shyly said hello to over loud music in a club. Some he’d blown it with. He wondered if they were right. Did any of them think about him out here? He hoped so. And he wished he was with one of them.

Finally he slept. It was a deep sleep of fatigue. He hardly moved all night but his ribcage expanded and contracted on me and he sweated. A buzzing mosquito, trapped inside the net, landed to extend its proboscis into him and suck blood up into its abdomen.

The stars twisted across the sky. Someone walked by in the dark and woke up the man in the camp bed next to us. He got dressed and went to keep watch. And we were alone in the courtyard.

He was already waking before his alarm clock rang. It was the brightening sky that made him turn over on me, and the chill that made him pull his sleeping bag up. It was a half-conscious bliss, being elsewhere, and the day ahead didn’t exist, only dreams of home that slowly corroded as he woke and realized he was lying on me, inside the netting, and a different sun was rising above him.

He coveted it: the longing to be back where he was safe and didn’t have any responsibility and wasn’t trained to do any of this. Where he didn’t have to lead anyone out of the gate again. He wished he didn’t have to. It was his private moment of cowardice before the day became real. He let it fester and was embarrassed, even though no one would ever know.

He hardened himself against it and it was gone, suppressed within him. He unzipped the net and swung his legs out, itched his thigh and left to wash himself and prep his gear, to take his men out there beyond the walls and try to make a difference.

The rhythm of shifts, patrols and downtime went on unbroken and became normal for him. But it did end. It ended before it should have, after he’d encased himself in armor, picked up his rifle and walked away from me one evening.

He never returned. Someone else came and cleared all his belongings from around me. They took the sleeping bag that smelt of him and packed it with everything else into a cardboard box. The man in the other bed was still there and he felt the absence.

After a few weeks, another man arrived to take his place and the rhythm continued. When he left, others came and I supported them one after the other. They were excited at first, apprehensive as they struggled to understand, sometimes disillusioned or resigned and always superstitious in the weeks before they were replaced.

Much later, after they’d gone and the sun had bleached my cloth, other men started to use me. They spoke another language and their uniform was different and they didn’t think of this as a distant country.

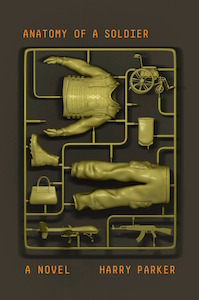

From ANATOMY OF A SOLDIER. Used with permission of Knopf. Copyright © 2016 by Harry Parker.