Porochista Khakpour on the Unrelatable Brilliance of Alison Rose’s Better Than Sane

"She isn’t interested in your ability to feel for her much less comprehend her."

The story goes that every New York City girl self-mythologizes. It’s almost part of our pact. You’ve worked so hard to get there, and then you arrive and you’re very much stuck—you hate it and yet you feel like you’re in an impossibly glamourous movie of you—you can’t afford rent or food but somehow you still do—you’re not quite any first, but never quite the very last—and that’s your life, the tension between fact and fiction always aswirl. Sometimes it’s so literal, the way certain New York City girls sees themselves in that particularly glossy black-and-white of celluloid, maybe the way we’d think some precious prairie girl could see her existence dipped in a foggy sepia. But as a friend of mine once said, Nobody does New York like California, and so maybe the Californian New York girls self-mythologize the hardest. I know I did, I know I sometimes still do. At those lowest moments in trying to make it all work, I thought there has to be something more than just the three thousand miles to show for my own endless ill-advised efforts.

Enter my favorite literary enigma, ultimate CA-NYC-girl Alison Rose. I wasn’t sure what I was getting into when I first read Rose’s only book, Better Than Sane: Tales from a Dangling Girl, as so much of it felt familiar and yet revolutionary. I suddenly found myself cast as one of her own characters encountering her in her own book: over-eager, naïve, intrusive, exhausting, but maybe (hopefully?) endearing in wanting very badly to sit next to her at a café neither of us could afford. I not only loved her, I hoped she loved me. By the time I recommended Rose’s book to a friend in the early 2010s, it was Renata Adler season, starting with the Speedboat revival—Rose and Adler were not just coworkers and friends, but Adler also supplied this book’s epigraph (“You are, you know, you were the nearest thing to a real story to happen in my life”)—and my friend wondered if Rose’s writing was in the same vein. Absolutely not, I said. Flash forward another handful of years to my cautiously recommending Better Than Sane to a handful of blocked memoir students hung up on the politics of right and wrong when telling the truth. Most of them felt like I did while twisting and turning through Rose’s taboo-acrobatics: Rose’s madcap-socialite-survivalism gave us hope somehow. I would feel bad recommending the book because it could retail for forty dollars, as it went out of print shortly after its 2004 release. For some, the book could never land but for the readers who got it, it was like nothing else.

Once in a while, when their journey was aborted, the book would find its way back to my desk. I’ve not only read it many times, I’ve owned it even more times.

*

In the last few years, every few months, it feels like, I would send tweets into a sort of ether, wondering if anyone knows or has heard of Better Than Sane. I had a deep desire to reach out to Rose somehow. On the way, I’d encounter others—mainly journalists and editors and authors—who had also read the book and who delighted in an opportunity to share its many inside jokes. No one seemed to know where to find her. The one time I encountered her—or came close, rather—was for these very pages. When Godine asked me what out-of-print books they might attempt to revive, one title came immediately to mind and it was Better Than Sane, of course. Like most everyone I recommend it to, the editors caught the bug when they read it. And so this little miracle happened: they contacted Rose through her agency and she agreed to this publication.

We are just shy of this book’s twenty-year anniversary, but even missing that mark by just a sliver—a sublime near-miss with symmetry—feels so deliciously Roseian.

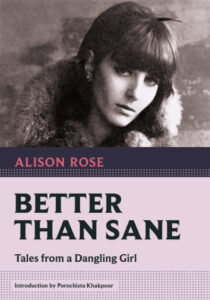

The original cover of Better Than Sane features a youngish Rose photographed by Bruce Weber, and the image almost exists out of time, or rather belongs to many times. It’s a very specific New York chic: all black, black long sleeves and black long legs, revealing the sort of thin frame one acquires not from working out but from doing or going without. Rose’s pale face blends with the white of the book’s background and the orange and pink of the graphics have the pop-y, somewhat subversive feel of a Warhol Factory production. But nothing on its cover is preparing you for what is inside.

And here we have the great irony of Better Than Sane, which sets it apart from so much of the canon of her literary it-girl contemporaries: this is the “coming-of-age” of a middle-aged “girl.” Rose’s first real job comes at forty, at the front desk on the writer’s floor of The New Yorker. It was dubbed “School” and eventually she found herself in a clique that, of course, she could only call “Insane Anonymous,” with George W. S. Trow and with Harold Brodkey as her anchors. One of Rose’s most interesting elegances is that we never fully realize the true nature of her relationships with both men. Brodkey, for example, had two names for Alison: “Already utterly ruined” and “My bride.” Trow, meanwhile, was as much mentor as he was accomplice, full of his own off-kilter adages and unsolicited advice gems, like “you have to have a machine gun in your heart.” There is no You can’t sit with us when it comes to Rose and Trow but there is You wouldn’t get it. And you wouldn’t.

There is a unique joy in how unrelatable this book is, but I also found myself very surprised by how much of this book I could relate to.The evolution from receptionist to staff writer at The New Yorker is only part of this story, but it’s a compelling one for any writer to consider. We are perhaps too comfortable with the classic Didion confession about her own chronic underestimation in Slouching Towards Bethlehem: “My only advantage as a reporter is that I am so physically small, so temperamentally unobtrusive, and so neurotically inarticulate that people tend to forget that my presence runs counter to their best interests.” Rose, who dabbled in acting and modeling, was never invisible. She might have instead offered her own strategy of demanding attention and disrupting norms. A bit of acting out is a great education for any writer. And, once on the page, there is that harder lesson that the best writers ultimately must confront: once you develop your own voice, you can expect a segment of your projected audience to never hear it. We could argue that without Rose and Trow there would be no “Talk of the Town” sound today. It’s easy to want more for her in this narrative. But how Rose was noticed—the negative attention that comes with being a woman that is even more unapologetic in being eccentric than beautiful—probably did her in the most.

But then again, who is saying she was done in? Who is to say she wanted more?

Rose, after all, committed to little else in letters after this book. Maybe she was fine, better than fine.

Self-pity, like relatability, is a language Rose does not speak. She isn’t interested in your ability to feel for her much less comprehend her, nor is she particularly caught up in being consistent. She is the person who says “I never did think of myself as a person who would get married and live in a house” and “The truth is, it can be a form of actual social day-to-day social torture to pretend not to notice the little dishes of poison married people offer you all the time,” but then, just a paragraph later, a man whom she calls Mr. Normalcy is valorized as “a whole family in one person.”

There is a unique joy in how unrelatable this book is, but I also found myself very surprised by how much of this book I could relate to. I am a CA-NYC-girl who has done some time in journalism and eventually cranked out a memoir, with a perhaps similarly dizzying array of New York lovers and friends. I was once in a self-im- posed estrangement from my own family. I have been lost far more often than I have been found, and it rarely bothered me. I rolled with all kinds of adversity with the absolute minimum of reflection far too often. Who can say if I was eating-disordered or just too destitute to afford food in my twenties, for example? I wasn’t about to worry about it. I was allergic to advice or anything prescriptive. I survived and often still survive in a way I can’t account for. And I probably will the leave the question blank if you try.

*

In this way, Rose can be an angel for us devils, a patron saint for people who don’t do patron saints. Maybe for those outside of us kindred spirits, something rubs off too. I happen to think with this book if you read all the way through its gorgeously indulgent, dazzlingly distracted, scrumptiously narrative-resistant spirals, you realize if you are not her, you are maybe becoming her, or so you should hope. It’s one way out! And she makes you her family in a sense. Gossip and insider buzzwords are thrown around like confetti here, thrilling and slap-dash, never mind this party features Anaïs Nin, Robert Oppenheimer, Otto Rank, Charlie Chaplin, Alfred Hitchcock, Tennessee Williams, Mike Nichols, Shelly Winters, Anthony Hopkins, and many more. And of course it always comes back to Rose—without even willing it, she manages to come across more compelling than anyone, but isn’t this how every memoir should go if truly honest?

It’s been many years since I’ve gone back, over and over, searching for Alison Rose, Googling for crumbs I may have missed after I first fell in love with Better Than Sane. Here’s eBay and Amazon stray copies that cost too much, a handful of reviews, a “books single women should read now or whenever” blog post, an interview where Refinery29 girlboss Christene Barberich highlights it as an educational read for her, and hilariously many links that lead to me—whether it is me mentioning her on Twitter, in a full essay in Bookforum, on my old Substack. I’ve been talking about this book nonstop since I first read it and it’s now my hope that I won’t be so alone with its secrets.

You should join me, over here. I’m at the cubicle, scanning the backs of heads for my Insane Anonymous; I’m whispering too loudly at the water cooler with the few of you with a similar aversion to nine-to-fives, a propensity for soft snark, and a taste for everyday scandal; I’m dishing on someone who wronged us at martini hour at the Plaza while we’re washing down benzo residue with our manyeth diet sodas, our collective scent somebody’s pipe smoke spiking designer-imposter perfumes (fragrances in which Ms. Rose would not be caught dead, believe you me.); and when we walk away, we take our time, because our prime has passed, because none of us are getting promoted, because the after-hours we linger in never count, because maybe we would have it any other way but you’ll never know.

Unless, of course, you know.

New York City, 2023

___________________________

Excerpted from Better Than Sane: Tales from a Dangling Girl by Alison Rose. Introduction Copyright © 2023 by Porochista Khakpour. Excerpted with the permission of Godine.