All funerals are the same, one buried body is much like another, the dead are interchangeable and eternal. The day when Sylvie is left behind in the cemetery’s depths, I have a prophetic vision of my mother’s burial. The nights are cold in spring, and Viviane has left me stranded among the deceased. I cry for a while, try to scale the fences with their large protruding prongs that might, if I straddle them, spear me through the groin, as happened to Romy Schneider’s son. I go to sleep surrounded by the chilly vegetation of my childhood cemetery. I am in Chicoutimi, but I am elsewhere too. In the dreariest moments of a dark night all cemeteries are one, and the dead who speak to me are from Témiskaming, Trois-Pistoles or Montparnasse, from Saint-Henri to Santo Domingo, from Notre-Dame-des-Neiges and Batiscan all at once. This night I am not in Chicoutimi, I am wherever the earth extends a serene welcome to its cadavers, but rarely in good faith, there’s almost always a knife hidden behind a back, a blade brought out as soon as the sky grows dark, the better to cut the cords binding the defunct to his demise, not to mention the perennial toads that on every night known to the world leap about among the black crosses and the dandelions busy feasting on human flesh. Forgotten, alone in the shadows, I curse Viviane and Sylvie. On my hands and knees in the muddy grass, before the grave of someone unknown, I read my mother’s name. My own as well, small and black, in letters almost totally worn away, which say FALDISTOIRE. I will swear on the heads of all whom I’ve known that I saw, in the depths of this long night, my name carved on a stone. I fall asleep on the grave that is to be mine.

Viviane never really had a sense of timing. She takes Sylvie’s death very hard. Several months after the accident with the snow blower, when I am sure she isn’t thinking about it any longer, she kills herself. Her farewell letter is a giant “Im goin to mis Silvi,” scrawled with a pencil she must have had some trouble holding in her hand. My mother has once more, this year, forgotten my birthday, because on the October day that I come home from school with my cardboard Toy Story hat, I find her hanging in the kitchen. An expert knot suspended from a hot water pipe has proved to be too much for the pipe, split open by the force of Viviane’s body dropping from the chair and swaying about, with her hands at her neck, as if she regretted having acted so soon. She is as beautiful as an onstage angel afloat thanks to some intricate machinery, she is a guardian angel descended from heaven thanks to some clumsy special effect, a two-bit illusion like those that dazzle the more gullible spectators in a theatre. On the table, her letter, five words. Just beside it, a big bucket of Gagnon Fried Chicken from her favourite restaurant, and a few greasy wipes. She’d offered herself one last treat before her demise.

Viviane babysat Sylvie during our whole childhood. After the death of her little Vivie-my-love, as if to repent for a non-existent sin, my mother began inviting her to the house every week. She made her cakes, rice pudding, which she knew I hated but made on purpose, she served her tricolour ice cream and took her to Gagnon Fried Chicken. As a child, I had Sylvie as a friend by default, but after the day of the snow blower, when she was totally pulverized, something changed in her.

The ghosts . . . The dead, I mean. You mustn’t say “ghost” because it’s a bad word, like saying “fairy” for a homosexual, or “cripple” for someone who’s handicapped. The dead who come back, those from my childhood I spend time with, have something different about them when they return. It’s the same for Sylvie and the same for Pierre-Luc, who also went back to school shortly after his skull was pierced by a pencil point. It will be the same, soon, for Sébastien, my best friend. My mother, for her part, died for good and never came back.

All funerals are the same, one buried body is much like another, the dead are interchangeable and eternal.

At her funeral I lose the name Faldistoire and become The-Son-of-Viviane. Her boy, her only son, he has the same face, he has her eyes, she didn’t find him under a toadstool for sure, her only child, my condolences, what’s your first name? Faldis . . . what? Faldistoire, that’s unusual, that’s beautiful I mean, Faldistoire, what does it mean? Open the dictionary, you stupid idiot . . . Why that name? My mother has left with her secret intact. Taking refuge in the bathroom to escape the embraces and the smell of hairspray, I think again about Sylvie’s empty, closed coffin, and my mother crying all the tears out of her body. It seems so long ago . . . I know that Viviane would have been sad to see that Sylvie wasn’t there for her own funeral. All afternoon, while the anonymous faces file past, the powdered cheeks jostling each other to kiss me, the handshakes, too firm, the strong perfumes and that, nauseating, of the flowered wreaths, I think of Sylvie, and of the mortuary tribute in our art class notebooks.

In her grave, my mother is wearing her favourite dress and a bouquet from a broom plant. We bury her as the flowers are beginning to fade, the day after the funeral, in the Chicoutimi cemetery, right beside the graves of Fernand and Ruth, her father and mother, in whose house

I am now going to live. The cold buffet in the living room amuses me. Just before her coffin is closed for good, just before sending her off to burn to a crisp in the bowels of the furnace, I slip in a few chicken sandwiches. The priest asks me if I want to throw on the first handful of earth. It’s sunny in the cemetery. It isn’t raining, there are no black crows, night is not coming on, the sun is there, the sky is blue, and no one, certainly not me, would say anything to the contrary. In my backpack I have the sketchbook with the drawings of my mother and Sylvie. Before the undertaker completely buries the urn, I bring it out and drop it into the hole. No one notices my occult ritual, my prophetic gesture, except the gravedigger, who doesn’t give a damn. He finishes burying my mother along with the sketchbook on which my name is written. I imagine it going to seed, bad seed in the soil of Chicoutimi, spreading afar, reaching away, putting out roots everywhere under the earth. Already my future is set down without my knowing it, without my being able to read it to correct the mistakes in grammar and spelling, the errors in logic that ought to be expunged from any narrative; my life and its tale are planted in the earth, already foreknown, decreed, determined, in this notebook where I drew my home.

I stay on alone with my grandparents when everyone has finally gone. My knees are stained by the damp earth and the green grass, just like when I fell in the backyard of the house in Des Oiseaux and my mother bawled me out because of the grass, it’s hard to get out in the wash. Leaving the cemetery to go to the parking lot, we follow a little dirt path bordered by trees. Along the way I see Paule’s grave. The statue of the angel paid for by the money she earned with her body, dancing with a stainless steel pole in her hand or a biker’s shaft in her mouth, has already been vandalized. Her praying hands have been torn off, her wings as well, the angel can no longer fly, her empty gaze and the smile at the corners of her mouth now seem despairing. No one has gone there to weep or to lay down flowers. No one, except for the black crows that wait for the toads to come out before diving earthwards and swallowing them whole.

__________________________________

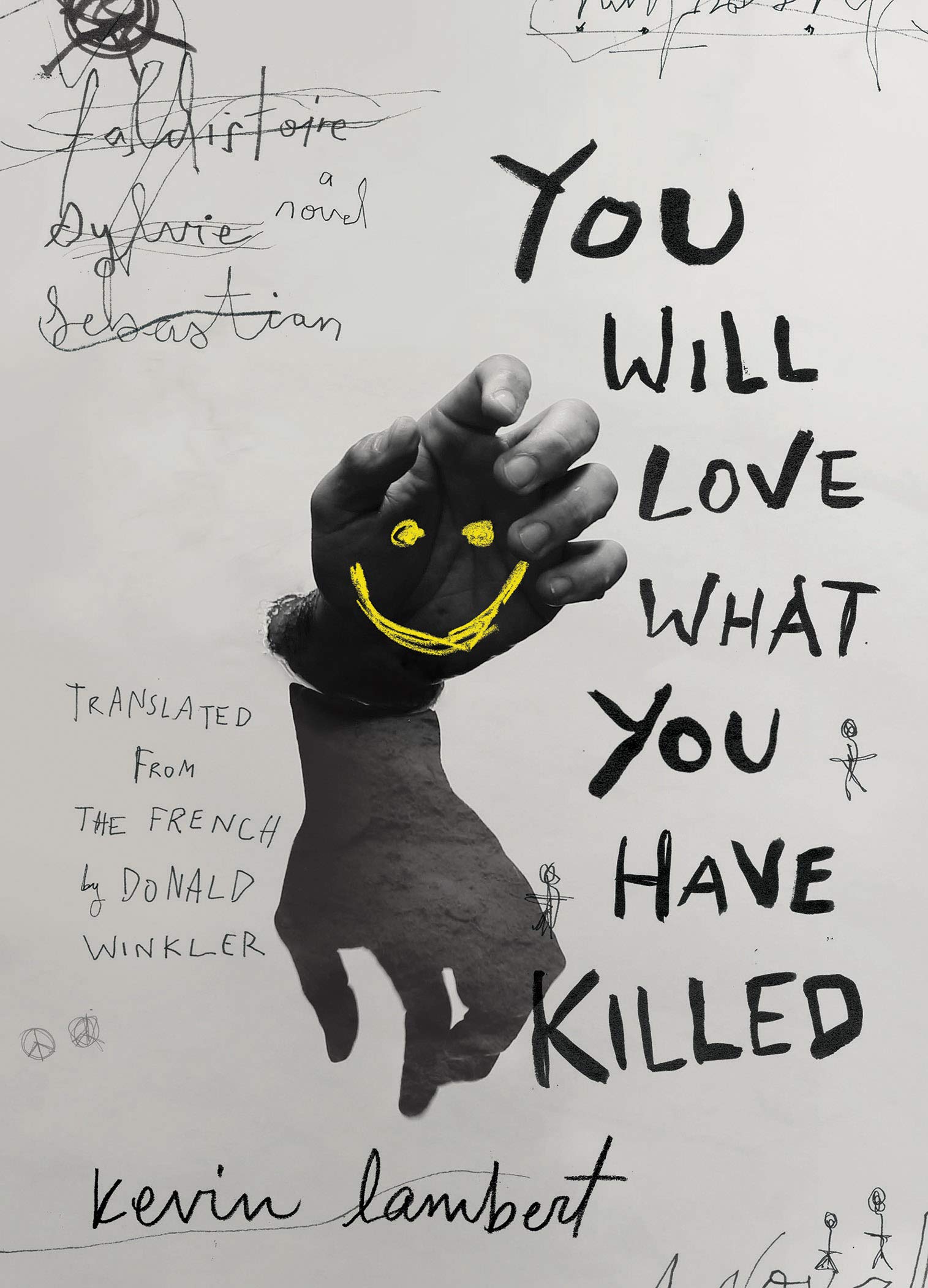

Excerpted from You Will Love What You Have Killed by Kevin Lambert, translated by Donald Winkler. Excerpted with the permission of Biblioasis.