Here is my impression of a play: Okay, so first you gotta imagine it’s a hotel room, right? Just a normal, boring-looking hotel room, on the nice end of things, as far as hotel rooms go. And the audience is coming in, and they’re taking their seats in this dinky little theater in lower Manhattan, barely bigger than a Winnebago, this theater, with seats that feel like someone just glued down some thin fabric over a block of hard metal. The main thing of a theater—like the whole point of it—is that there’s going to be a lot of sitting in it, so you’d think they would at least consider investing in some comfortable chairs. Word to the wise: if they can’t even get that part right, which absolutely most of the time they cannot, then buckle the fuck up, because I can tell you right now you are in for an ordeal of an evening.

Anyway, the people are walking down the aisle, trying to find their row, which is pretty much impossible, because even though there are only three rows in the theater, they’re labeled like row a, row jj, and row 2a and a half, and everyone’s looking at their ticket like, “I’m supposed to be in row twelve. Where the hell is twelve?” But anyway, they’re walking down the aisle—and the carpet has a weird bump in it that everyone needs to be careful not to trip over—and they sit down and they look at the stage and they see a bed and a chair and a minibar, and they say, “Okay, so I guess this play takes place in a hotel room.”

Half of all plays ever written take place in hotel rooms just about, so it’s not a huge shock, and half of those are about guys on business trips spilling their guts to hookers who, it turns out, are actually really sweet. This play is not about that, but for a second it feels like it could be. Like when the audience comes in and they see the hotel room, they have to check their programs, because it’s like, “Oh shit, is this going to be another one of those plays about a sad guy and a sensitive hooker, and the guy doesn’t even want to have sex with her, he just wants to talk? But then later, they have sex anyway, and she doesn’t even charge him, because it turns out they fell in love? And of course the hooker takes her bra off, right when she’s facing the audience? God, this isn’t going to be one of those plays, is it?”

So then everyone’s looking at the program, right? To try to figure out whether it’s one of those hooker plays. And they’re reading the notes from the artistic director or whatever, and the cast bios, and it’s like, “Ooh, did you see this actress played a dead body on a Law & Order once?” And there’s a thing in the back about how we need you to donate money to the theater, like how Theater is so Vital and Important, like as if you didn’t spend your money already on a ticket just to be here. Like as if they’re doing you a favor to show you this play. Like as if the play-writer’s parents hadn’t already spent thousands of dollars to send this guy to a fancy liberal arts college so he could learn how to write plays good.

As if his big sister didn’t just drive all the way down from Syracuse to be here, leaving the kids with her dirtbag ex-husband, who you just know is going to say some dumb shit that traumatizes them while she’s gone or he’s going to show them a dead cat in the alley or some old wrestling videos or something, and when she gets back she’s going to get a call from the school because her kids won’t stop meat-hooking and pile-driving everybody.

But anyway, the play. So the lights go down and the fancy play-bellhop comes to the front of the audience to make an announcement. And the announcement is basically: “Hey! Dummies! Turn off your cell phones! You’re at a play!” But then also maybe there’s a part about how this theater company has more plays coming up, and if you like plays, maybe you could buy tickets to see some more of them! And it’s just like Jesus, Play, maybe for one second you could stop trying to sell me on the Concept of Plays; if I want to see more theater I know how to do it, but anyway I don’t even really live here; I’m just trying to be a good older sister to my idiot play-writer brother—who, by the way, couldn’t even get me into this play for free. This is another true fact about plays, which is that on top of everything else, you have to pay for your own ticket, because I guess that’s what being supportive is. Because I guess if you’re not buying a ticket, who is? Mom and Dad? Yeah, right. As the fancy play-bellhop walks back up the aisle (stumbling over the weird bump in the carpet), you look around at your fellow audience members in this half-empty theater and you wonder if the only reason any play is ever successful at all is just on account of friends and family “being supportive.”

So then the play starts and the first thing that happens is two ladies burst into the hotel room, one after another. These ladies are supposed to be sisters, probably, because when plays aren’t about hookers, ninety percent of the time they’re about sisters. But, of course, because it’s a play, these sisters look nothing alike. For starters, one of them’s like fifty and the other one’s like twenty, because apparently when you’re hiring people for plays, it’s impossible to find two women who are about the same age.

The older one goes right for the minifridge and pulls out a bottle of white wine, even though since it’s a play, the white wine is actually water, if there’s even something in the bottle at all, which—spoiler alert for all plays—there probably isn’t. The younger lady kicks off her shoes and jumps onto the bed. And they start talking in that very fast, stutter-y I’m-a-character-in-a-play way that guys who write plays think is naturalistic, even though nobody actually talks that way except for people who just tried cocaine for the first time.

“Okay, okay, but can we— Okay, but can we talk?” says the one on the bed.

“Drink first, then talk.”

“Virginia, can we talk, though? Can we talk, Virginia?” People are always saying each other’s names in plays. That’s like the number one thing that happens in plays, is people just wedging names into sentences.

“You think I don’t want to talk, Maggie? I am well aware there are things about which we need to talk.”

“She’s pretty.”

“Am I drinking yet?”

“But she is pretty. You have to give her that.”

“Well, of course she’s pretty, Maggie. This is Dennis we’re talking about. You think he’s just going to date some old possum that fell off the back of a truck full of boots?”

This gets a big laugh from the audience, and it’s like: Why? And I’ll tell you why. It’s because the standards for comedy in plays are very low. Like if you heard someone say that in a movie, you’d be like, “Where is the joke?” But I guess because this is a play and, damn it, it’s out there doing the best it can, we’re all just willing to meet it halfway and laugh at some of its words.

Meanwhile, it is completely unclear how old the sisters are supposed to be, but if you had to guess you’d say they’re probably in their twenties, because apparently the older sister is supposed to be you, and the younger sister is supposed to be Shannon, and so it would be pretty weird if the younger character was any older than twenty-six, because that’s how old Shannon was when she died.

As soon as you realize the sisters are supposed to be you and Shannon, the bottom of your heart falls out and everything inside your heart spills into the lower half of your body. At first, you think maybe the characters are just inspired by certain aspects of you and Shannon, but the more you watch, the more you realize, no, the older sister is you, cutting and callous and cruel, and the younger sister is Shannon, as Shannon as anyone has been since the real Shannon overdosed six years ago.

And the “Dennis” the sisters are talking about is your little brother, Dusty, the play-writer, and the “pretty girl” is his ex-fiancée, Tiny, and this play is from when you all went to Niagara for your parents’ anniversary, which, by the way, Dusty did not tell you that’s what the play was about, but to be fair, he did send you a link to a website, and you did not click on the link, so maybe this one’s on you.

Anyway, “Dennis” enters soon with his girlfriend, “Tracy,” and the whole rest of the play takes place in this one hotel room, because God forbid the theater uses some of the money it’s making off its “proud sponsors” (which is just like a real estate firm where one of the actors’ dads works) to pay for a second set.

And the character based on you is loud and cynical and the character based on Shannon is sweet and goofy and full of energy. And the character based on Dusty is awkward and neurotic, much more awkward and neurotic than Dusty really is, but the character is neurotic in a cute way, which Dusty is not. Like, for example, it’s cute for someone to be tongue-tied around his own girlfriend because he’s thinking of proposing. It’s not cute for someone to write a play about his family and then not tell his family. It’s not cute to make his sister do the five-hour drive down to New York City and get a room at a hotel (because God knows she’s not sleeping on his filthy couch again) and buy a ticket to see his play and then, SURPRISE—and also, BY THE WAY, the character based on you is an alcoholic. And the character based on Shannon is addicted to pills, which you can tell by the way she keeps taking pills. Like as if it was obvious at the time, like as if any rational person could’ve seen it, could’ve said something—but of course it wasn’t obvious, because if it was obvious, you would have said something, would have done something. Of course you would have.

And as you watch this weird mirror version of your family trip to Niagara and you hear people around you laughing at the “jokes” and disparagingly murmuring their judgy little murmurs, you begin to feel very, very naked and exposed. You feel like you’re a record store full of strangers; here they go, ambling up your aisles, riffling through your stacks. The Museum of You is now open for business, every piece of you hung up on a wall, laid bare on a table, harshly lit and awkwardly described. It’s like one of those dreams, is what it’s like. You know the kind of dreams I’m talking about? It’s like one of those.

This is a feeling that happens sometimes when you go to see plays.

So, anyway, after a full act of that, the lights come up and it’s intermission, so you get to take a quick break before another full act of that, and your brother turns to you and says, “What do you think so far?”

And you say, “I’m still processing it,” which is a thing you can say about plays, which means “I don’t like it.”

And Dusty says, “Yeah, I know it’s a lot to process.”

And you say, “I gotta go pee.”

You go out to the lobby, and there’s a line for the ladies’ room about a thousand miles long, and it’s like, how is this possible when there is literally almost zero people attending this play? And of course there’s no line for the men’s room, and you would think this is a problem that plays could have figured out by now, considering this always happens at plays. You decide to just use the men’s room, and if anyone gives you a hard time about it, you can just tell them the play-writer is your brother. If anyone gives you a hard time you can say, “You know the drunk sister? In the play? That’s me.”

Nobody gives you a hard time.

After the bathroom, you decide you want a glass of wine and some peanut M&M’s, but the line is long at the bar too, and for a moment you consider cutting to the front and making a big scene—because what are they going to do, kick you out?—but you don’t want to embarrass Dusty like that (even though he clearly has no qualms about embarrassing you), so instead you go outside and call your dirtbag ex-husband.

“How are the kids?” you say.

“Kids are great—Cody, put down that blowtorch!”

You’d roll your eyes if you still had any eye rolls left for this guy—if your five years of marriage hadn’t left your eyes completely depleted of rolls.

“You’re hilarious, but I’d better get them back with all their fingers.”

“Sure, sure. And if you’re lucky, maybe I’ll even throw in a couple extra fingers, just because I like you.”

“You’re not letting them drink soda, are you?”

Because of course your natural response to affection is criticism. Of course it is. Isn’t that so like your character, after all? Isn’t that what “Virginia” would do?

You can hear your ex-husband tense up over the phone. There’s a pause just long enough for an implied “Not this again,” and then he says, “How’s the play?”

Because of course his natural response to criticism is to change the subject.

“It’s about us,” you say. “The whole thing’s about us.”

“What, us? You and me?”

“No, not you, dumbass, me and Dusty and Shannon.”

“Shit, really? What about you and Dusty and Shannon?”

“I don’t know, man. How we’re all a bunch of assholes?”

“Jesus,” says your dirtbag ex-husband. “Of course fucking Dusty would do this to you.”

“Yeah.”

“Did you know?”

“No, I didn’t fucking know—are you kidding? You think I would’ve come down here?”

“You know, this is what he does. He pushes people away. And then he’s surprised when like your parents don’t wanna—”

“It’s just intermission. I gotta go back in before it starts again.”

“No. Dakota. Go back to the hotel, or go to a bar or something. You don’t need to put yourself through that.”

But of course, you do.

On the way back in, you get a glass of wine. The theater can’t legally sell you the wine because it doesn’t have a liquor license, but the “suggested donation” is seven dollars. You take the suggestion under consideration but ultimately decide to donate nothing, because isn’t just being here donation enough?

Act two starts and the two sisters burst into the room again and the character based on Shannon kicks off her shoes again, and this time one goes flying and hits the fake wall of the hotel room and the whole set kind of wobbles a little and the audience laughs, but you are furious. You imagine your brother in rehearsal with this actress, showing her exactly how to kick off her shoes in the same way Shannon used to every time she entered a room. And it’s not like that was some big family secret or something, the way she kicked off her shoes, but it feels to you that the act of re-creating it somehow degrades it. Like the next time you think about Shannon kicking off her shoes, will you be thinking of Shannon? Or will you be thinking of this actress?

The second half of the play is much weirder than the first half—part of it might be a dream, but it’s kind of hard to say.

At one point the lights go all red and the actors turn out to the audience and talk in unison in a weird monotone. This is a thing that happens in plays sometimes when the director is worried

that the audience might be getting bored, so he makes the actors look directly at them so they get self-conscious and have to pay attention. There’s a strobe light and a fog machine, and late in the show, a cup gets knocked off a table and rolls off the stage and one of the actors has to chase it into the audience, which is also a thing that happens sometimes in plays.

Then at the end there’s a blackout, and your brother starts clapping immediately, like before anyone has a chance to breathe, even, like as if he’s afraid that if he doesn’t start clapping, nobody else would. Maybe no one would know the play’s over, like. Maybe you’d all just sit there in the dark, thinking, What happened to the play? Is it going to start again? Is this part of it?

Personally, you wouldn’t mind a moment—a silent moment, in the dark—to think about what you just saw, to think about what you’re going to say, to decide whether you want your brother to see you crying. Most plays would probably be better if they gave you a second to collect yourself at the end, but most plays don’t, and this play doesn’t.

The lights come back on and the actors take their bows, and the weirdest part is that you clap for them. You find yourself applauding for this broad burlesque puppet show of your life, as if you really found the whole thing to be a marvelous endeavor. You will think about this night a lot in the months ahead, and

the one thing you will ask yourself over and over is: Why did you clap?

After the play, your brother wants you to come to dinner with him and the cast and crew. Apparently, in New York, “dinner” is a meal you eat at eleven o’clock. I guess when you’re an artist you can afford to take creative license with certain concepts, especially when you don’t have a job to be at in the morning, or a family, or any shame about showing up at a diner at almost midnight for “dinner” and then ordering waffles.

Anyway, all the people from the play are very excited to meet Dusty’s sister.

“So you’re the real Virginia,” says the actress who played Virginia.

“Actually, I’m Dakota,” you say. “I’m pretty sure Virginia’s based on our other sister Massachusetts.”

“Oh, is that the one who passed away?” says the actress.

And Dusty says, “She’s joking. We don’t have a sister named Massachusetts.”

Then everyone ignores you for a little bit, because they’re show folk, and show folk think that what makes a good conversation is each of them taking turns just saying their funny stories at the room for a half hour. This is the most brutal part, honestly—that after you just spent two and a half hours watching their show, they took you to a second location where there’s more show.

Eventually, after they get tired of talking about themselves, the theater people are ready to hear you talk about themselves, and one turns to you and says, “Dakota, what did you think of the play?”

You finish your beer and say, “I thought it was unrealistic that at the end, they all confront the sister about the pills. Didn’t feel real to me.”

Everyone gets all awkward. The actress who played Tracy laughs because she thinks you’re joking, but then when she sees that no one else is laughing she says, “Excuse me,” and she gets up from the table and you never see her again for the rest of your life.

Your brother shakes his head. “Jesus Christ, Dakota, it’s a play.” “I’m just saying it didn’t feel real.”

Then the director says something like, “I understand what’s happening here. You see, Dakota, in fiction, sometimes things can play out counterfactually—or differently to the way they did in real life, and the difference between the two is what gives the fiction its vibrancy.”

And you say, “Oh, wow, really? Is that how fiction works? I didn’t fucking know that, about fiction being counterfactual and all. Thank you for elucidating to me what fiction is.”

And your brother says, “Dakota, calm down.”

“Why? Am I embarrassing you?”

“Yeah, actually.”

“So, just to be clear, this is embarrassing? Everything in that play—all the dirty laundry—that’s, what, fiction? But this is embarrassing.”

And all the theater people avert their eyes because they’re real uncomfortable that they’re for a moment not the center of attention, and Dusty says, “Can I talk to you outside?”

So you go outside and you light a cigarette, and a man with the restaurant says, “Excuse me, ma’am, you can’t smoke within fifteen feet of the outdoor seating area,” and if that isn’t the most bullshit part of all of this, then I don’t know what.

“What’s going on?” says Dusty.

You shake your head, because if he doesn’t know by now, what the fuck?

“Look,” he says, “I know that was rough to sit through, but how do you think I feel? I’ve been working on this play for the last year and a half.”

You snort. Boy, isn’t that something?

A bus goes by with an ad on the side for a play—a real play, on Broadway—and you wonder if every play—every piece of narrative “fiction”—is just some excuse for the guy who wrote it to talk some shit.

“Who said that’s okay?” you ask. “The stuff you put in that show, who gave you permission?”

Dusty looks at his feet. “Look, when you’re an artist, it’s all grist for the mill.”

“No. I’m not your ‘grist.’ Shannon is not ‘grist.’ You need to deal with your shit.”

“I am trying to deal with it. This is how I’m dealing with it.”

You can’t look at him now, because if you do you’ll start crying. You should probably just drop it there, but instead you say, “Yeah? And are you also dealing with how I’m a bad mother? And an alcoholic? Is that all stuff you need to deal with in your play?”

“When did I say you’re a bad mother?”

“You think I’m a bad mother because I dropped Taylor on the head once.” And now you are crying, which is—forget what I said earlier—the actual most bullshit part of all of this.

“What are you talking about?”

“You put it in your play that I dropped Taylor on the head, and it’s a big joke, and everyone’s laughing, and I’m sitting there thinking, All these people think I’m a bad mother.”

“Did you drop Taylor on the head? I just made that up, it wasn’t about you.”

“But the whole thing was about me. And Shannon. And you, and Mom and Dad. And how we’re all bad people because we didn’t save her.”

And then you can tell Dusty wants to say something, but then he thinks better of it, but then after a moment of silence, he can’t help himself and says it anyway: “Well, we didn’t save her, did we?”

Oh, I forgot to mention earlier—another stupid thing about plays is that sometimes there’s a sound effect of a phone ringing, and it keeps going for a beat even after the actor answers the phone. It’s pretty funny when that happens.

Okay, what was I talking about? Right, outside the restaurant. Okay.

Okay.

“Dusty,” you say, “we didn’t know. There was nothing we could do.”

And now he’s getting angry: “Really? You didn’t know? When we went to Niagara and she kept slipping off to the bathroom all weekend? When she kept falling asleep at the dinner table—when she would giggle for a half hour and touch everyone’s face—none of that was suspicious to you?”

“I just thought she was being goofy—she was being Shannon.”

“Yeah, she was being Shannon, because Shannon was an addict.”

“And you’re saying if I wasn’t such a drunk I would have noticed. You think Shannon overdosed because I—”

“I’m just saying it was obvious. All weekend Tiny kept saying, ‘What’s going on with your sister?’”

“Well, I’m sorry I’m not as astute an observer of human behavior as Tiny is. If it was so obvious to you, why didn’t you say something?”

“I don’t know,” he says, and he chokes out the next line like it’s snagged on a hook in his throat: “I will never know.”

You feel bad, but then you feel angry at him for making you feel like that, when he’s the one who should feel bad after the stunt he pulled, so you say, “Shannon is not your story to tell. I am not your story to tell.”

And he says, “I’m sorry you feel that way.”

You nod. That’s basically what you’re going to get from Dusty; I don’t know why you thought you’d get anything different.

“I’m going back to the hotel,” you say. “How much do I owe you for dinner?”

And he says, “Don’t worry about it.”

And you say, “No, come on, let me pay.”

And he says, “No. Don’t worry about it.”

So, good, I guess. One less thing to worry about.

You start to walk away, and Dusty calls out, “I guess it’s a good thing Mom and Dad didn’t come, right? They would have hated it.”

You turn back. “I don’t know, man. I don’t even know what they’re about anymore.”

If there’s one silver lining to the cloud of shit that was tonight, it’s that at least the play wasn’t about what happened after Shannon died, about how your parents retreated into themselves, cut their losses—how when you tried to call them, your mother said, “I’m sorry, Dakota, talking to you . . . it’s just too much for us right now”—how when she said that, your own grief tripled. You don’t think you could stand to see a play about that.

“I sent them an email, but . . . I don’t know why I thought they would come.”

You look at him. And the play version of you would hug him. The play version of you would say, “Dusty. Whatever is going on with those two, I promise you it is not your fault.”

But the real version of you just looks at him and offers a sympathetic little nothing of shrug, which somehow is supposed to communicate all the things that need to be communicated.

And he says, “Well. Thanks for coming.”

You go back to your hotel room, by yourself, and head straight for the minifridge and pull out the bottle of wine you bought earlier.

The room has two beds, because you couldn’t get one with just one bed, and you wish Shannon could be there. For all of it, actually, you wish Shannon could’ve been there. You would have liked to hear what she had to say about the play, so even just for that.

You know it wouldn’t have bothered her the way it bothered you, which is also pretty annoying, because why do you always have to be the one who gets bothered by things? After dinner with Dusty, you’d go out for drinks, just you two, and after drinks you’d head back to the hotel room that you were sharing and Shannon would kick off her shoes.

“I liked it,” she’d say, which of course would drive you crazy.

At the very least, Shannon would’ve gotten a kick out of the fact that the actress who played her was on a Law & Order once. “Fancy,” she would say. And she’d look at you all smug, like this was some great achievement on her part. This would bug you at the time, but looking back at it, you’d think it was hilarious. For months afterward, you’d think back on this moment—Shannon saying, “Fancy,” and sitting up straight in her seat like the goddamn Duchess of Wales—and it would make you smile

every time.

So even just for that.

__________________________________

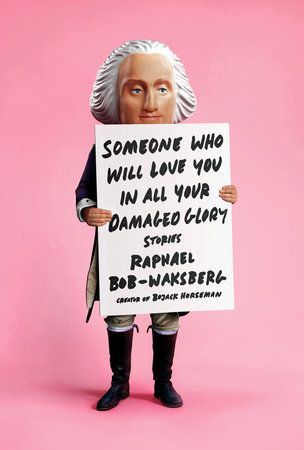

Excerpted from Someone Who Will Love You In All Your Damaged Glory. Copyright © 2019 by Raphael Bob-Waksberg. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission from the publisher.