You Can’t Have Creativity Without Boredom

Aaron Angello on the Stillness of the Imaginative Mind

When I was a child, my mother used to tell me that boredom was just a lack of imagination. I’m sure her parents told her the same thing. The expression was probably everywhere in popular culture.

I dug a little, and it seems the quote she was referencing comes from Susan Ertz’s 1943 novel, Anger in the Sky, in which Stacy, the youngest daughter of the wealthy Mrs. Ansthruther, says to her mother, after a discussion of the kinds of lives people should live in their later years, “I think I agree with everything you said, but wouldn’t people get bored if they lived so long?” Mrs. Ansthruther replies, “Bored? Never let me hear that word from you. Boredom comes simply from ignorance and lack of imagination.” In other words, the creative mind can’t be bored because boredom and creativity (i.e., imagination) are opposing states of mind.

This kind of thinking is pervasive still, and I’m fascinated by it. “Boredom is the great evil,” they tell us. “It’s the destroyer of productivity. If you’re bored, you should get off your backside and do something about it.” However, I’ve come to believe differently. I want to take a stand in favor of boredom as a generative approach to the creative process. Rather than boredom resulting from a lack of imagination, I think it provides access to the imaginative mind.

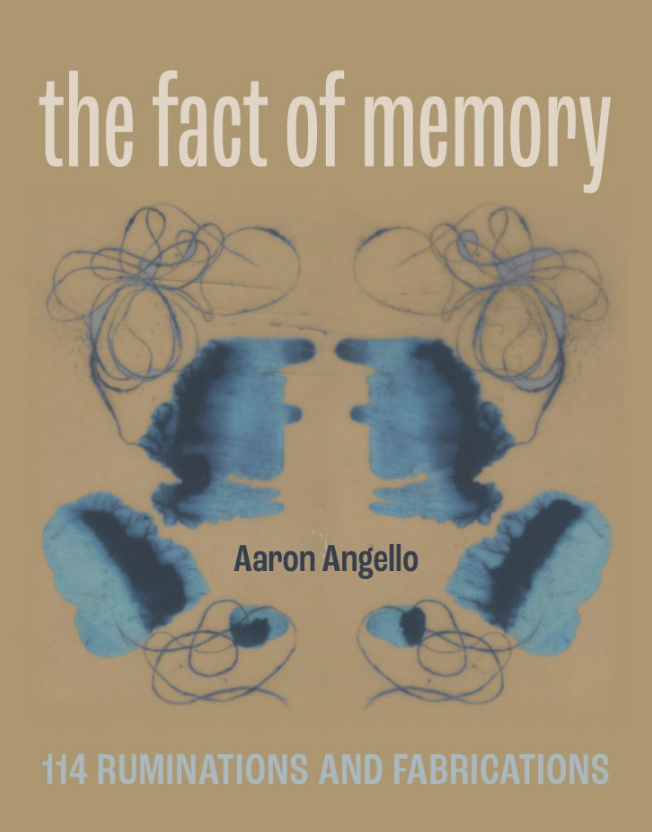

My recent book, The Fact of Memory: 114 Ruminations and Fabrications, is the result of a daily practice in which I would wake obnoxiously early in the morning, sit in a straight-backed chair by a window in my Boulder apartment, and think about a single word from Shakespeare’s 29th Sonnet.

I had written each word of the sonnet, in order, at the top of a page in a sketchbook. Each morning, I’d turn to the next word, sit with it for a half hour or so, then write. My self-imposed constraint was that I could not stop writing until the page was full, and I could not write onto the next page. I didn’t give myself any other constraints regarding genre, fiction or nonfiction, style, diction—anything. I did the exact same thing every morning for 114 days.

What I realize now, in retrospect, is that I’d stumbled upon one of the most productive approaches to writing I’ve ever tried. I just sat in a chair, facing forward, always the same, morning after morning. There was nothing stimulating about that process, that practice.

Thinking about why that process was so productive for me, I remembered an instance from many years before I began writing that book. I was in my twenties, living in Los Angeles, trying to be an actor and musician, and I was working as a caterer at a summer filmmaking program for teens. It, like all catering work, was terrible.

If we devise ways to access our beyond-consciousness, we enter the realm of potentiality.

There were just two of us on the job: a very accomplished, classically trained actor two decades my senior, and me. The work was physically demanding. We had to load big, black, insulated food pan carriers up tricky staircases in an office building, set up a line of chafing dishes filled with beef and pasta, and fill and lug five-gallon beverage dispensers with instant lemonade from the kitchen to the buffet table. It was also mentally—not exactly demanding—but taxing. Constant.

We had to help throngs of 15-year-old Scorseses figure out how to use a ladle or how to carry a paper plate loaded down with corn-on-the-cob and baked beans from the buffet table to their dining table without dropping it on the floor or on themselves. We had to maintain small talk with staff while keeping the buffet table clean and attractive. It was constant, and, frankly, really hard.

At the end of the day, we pulled everything back into the kitchen. One of us would stay out front where the students were finishing up their lunches, and the other would take care of dishes in the back. For the first few days, I took the dishes while my partner packed up out front, dealt with staff and students. After all, doing dishes was the dirty/disgusting job. I was doing him a favor. Then, a few days into the gig, he asked to do the dishes.

“No, no, I got it. You go ahead and take the front.”

“No, really, I’ll take dishes…”

“No, I’m happy doing them…”

“I WANT TO DO THEM! I WANT TO DO THEM!” He completely lost it. I remember him shaking, his veins popping out on his neck and temples, tears in his eyes.

What I realize now is that washing those filthy, fishy, barbecue-y dishes was in fact an escape. It was repetitive, it was physically isolating, and it was terribly boring. And it was the only time during that job when my creative mind was freed from tasks, from processing all the ridiculous things it must process at a job like that. Both my partner and I wanted to go back into the kitchen, thrust our arms into the murky dishwater, and stop engaging in the trivial for a half hour or so.

In an essay called “Railway Navigation and Incarceration” in his book The Practice of Everyday Life, the French Jesuit and cultural philosopher Michel de Certeau paints a picture of a passenger on a train, an “incarcerated traveler.” Their body is disciplined, in Foucault’s sense: they’re sitting in the chair, facing forward, very properly. They sit next to the window unable to do anything but watch the world outside pass by. Everything in the train car is still. Outside the window, the world appears to be still.

The writer must give themself a task in which they don’t think about what their body is doing. Walking is good.

Still, the train is speeding forward, along a rail. The passenger is isolated, bodily, and though they are moving, they are unable to move. They are cut off from the world through which they are speeding, and according to de Certeau, “this cutting-off is necessary for the birth …of unknown landscapes and the strange fables of our private stories.” It is the mundanity of the entire experience, set apart from daily, lived experience, that frees the mind to access the otherwise inaccessible, to remember the forgotten, to ruminate and to recollect.

For de Certeau, the movement of the train is crucial to accessing the imaginative mind. That makes perfect sense to me; I’ve written many poems on a commuter bus between Denver and Boulder. However, my experience tells me it is the fact that the body is in a pre-determined position (i.e., sitting, facing forward), and the mind is freed from its usual, constant engagement with a barrage of insignificant things that allows the creative person to move from the limitations of the conscious mind to the vast potential of what I like to refer to as the “beyond-conscious” mind. On the train (or bus, or chair in the living room), we move from a state of trivial engagement to a state that we might call boredom, and that state is a point of access into creative possibility.

Similarly, walking can provide access to that state. Writers, famously, are often walkers. Walking is an effective and generative pastime for creative people. Poets from William Wordsworth to Robert Frost, Wallace Stevens to Susan Howe have all made walking a part of their practice.

In their excellent article “Give Your Ideas Some Legs: The Positive Effect of Walking on Creative Thinking,” Marily Oppezzo and Dainel L. Schwartz argue that “walking boosts creative ideation in real time and shortly after.” In a series of experiments, they found that taking a stroll “is an easy-to-implement strategy to increase appropriate novel idea generation,” even more effective than sitting.

That may well be so, but still, I contend that it is the disciplined body, in motion in this case, that frees the mind from trivial obligation. I also contend that for walking to be effective, one can’t walk new, exciting paths. One can’t walk unfamiliar, uneven streets or trails. One’s body must know the path so well that the mind is not obliged to actively navigate potential dangers; it must not be stimulated by beautiful or surprising things around every unknown corner. In the general discussion of their study, Oppezzo and Schwartz point to necessary further study to determine if access to creative ideation “may be the mind-freeing quality of engaging in a comfortable task (e.g., knitting), rather than exercise.” They also propose the idea that “walking may be effective in many locations that do not have acute distractions.” This, I think, is my point.

The trick, I’m arguing here, is that the writer needs to put themself in the position of the “incarcerated traveler” to move beyond the consciousness and into the beyond-consciousness. They must give themself a task in which they don’t think about what their body is doing. Walking is good. Riding a bus is good. David Lynch (arguably one of our most creative filmmakers—I’m a Lynch nerd) encourages transcendental meditation. When I wrote The Fact of Memory, I sat in a chair, meditated upon a word, and wrote. I didn’t plan anything. I didn’t have anything else I could do. I got myself bored.

If while writing, we can only access the place from which we operate throughout our daily lives, a conscious place, we can only reproduce what already exists. We can only maintain the status quo. The ordinary requires us to repeat what is already there. The ordinary is the place of cliché and derivativeness in writing. At the risk of sounding a bit dramatic, it’s also the place of existing power structures and systems.

If we devise ways to access our beyond-consciousness, we enter the realm of potentiality. Possibility only exists there. There is value in boring tasks that engage the body but not the mind. Boring tasks and practices free the creative mind from the constant inundation of the ordinary. We’re taught that boring is bad, but it may well be the only way out of a system that demands our constant attention to maintain itself.

_____________________________

Aaron Angello’s The Fact of Memory is available now from Rose Metal Press.

Aaron Angello

Aaron Angello is a poet, playwright, and essayist from the Rocky Mountains who lives and feels remarkably out of place in the charming, but very Eastern, town of Frederick, Maryland. He received his MFA and PhD from the University of Colorado Boulder, and he currently teaches writing and theater at Hood College. Visit his website at here.