You Can Never Go Back: On Loving Children's Books as an Adult

Why Visiting Old Fictional Friends is So Bittersweet

I’ve never gotten over growing up. I must’ve longed to grow up at some point, I suppose, fantasizing about unknown, illicit future pleasures as all kids do—but once I’d done it, I quickly wished I hadn’t. When I see a pair of third graders slumping home after school with backpacks and sneakers trading meaningless conversation, I feel nothing but surly envy. Passing a playground with careless shrieks and jeers from swing sets and monkey bars, I want to join. But I cannot; that would be creepy.

I’d trade sex and booze and wisdom—all the best parts about being Grown—if I could have back those other things. Colors brighter, smells stronger, days bleeding on forever, and oh . . . reading. In childhood, there’s almost nothing to keep you from reading. Meals are prepared; you needn’t get up for work, put on makeup, or fill your car with gas. As adults we read books because they’re “good” for us, or they’ve been recommended by smart people, or a teacher assigned them, or we don’t want to make eye contact on the subway. But the books we loved growing up had cosmic power—they chipped away at and gnawed upon and shaped our identities. “Perhaps it is only in childhood that books have any deep influence on our lives,” wrote Graham Greene. “In later life we admire, we are entertained, we may modify some views we already hold, but we are more likely to find in books merely a confirmation of what is in our minds already.” In other words, kids are terrific bundles of potentialities.

The structure of Bruce Handy’s book Wild Things: The Joy of Reading Children’s Literature as an Adult imitates a growing child. It is part historical survey (nimbly covering a century of American and British kid’s books), part biography (detailing the lives of writers from Dr. Seuss to E.B. White to Maurice Sendak) and part memoir. Beginning with the eerie, distant majesty of Margaret Wise Brown’s Goodnight Moon, Handy moves toward the cold trauma of Beatrix Potter and poor hunted Peter Rabbit, before working up to the adult-verging antics of Laura Ingalls Wilder and Beverly Cleary’s Ramona. “Many of us say we loved Green Eggs and Ham or The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe or Charlotte’s Web when we were young, but that’s often where the conversation ends, in a hazy, nostalgic glow—a seminal reading experience reduced to a yearbook page,” Handy writes. And he has a point: Why on earth don’t we discuss these books more often? Each time I mention Mary Poppins or Kenneth Grahame to friends, I get, “Yeah, I remember that one, sort of, it was good—who wrote it again? Have you seen The Deuce?” Robust grown-ups dream of touring Paris, luxuriating on Santorini shorelines, hiking Machu Picchu. I’m down to visit those places, but I’d rather go to Wonderland, Neverland, Oz, Narnia, Middle Earth, Hogwarts, or the Hundred Acre Wood.

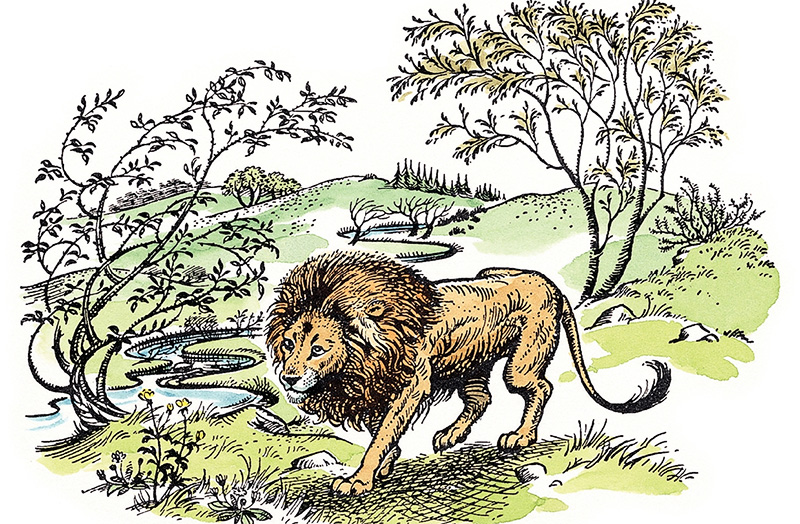

From The Chronicles of Narnia. Illustration by Pauline Baynes

From The Chronicles of Narnia. Illustration by Pauline Baynes

So: most adults aren’t reading children’s books. They’ve haughtily moved on. Handy found a means to circumvent the social inconvenience of haunting library kid’s sections, though: having kids of his own. He notes the exquisite melancholy of revisiting favorite books with offspring, as if vainly hoping to experience a second childhood while they have their first. “By one measure, I suppose, you are holding in your hands a work of sublimated grief,” he writes of reconnecting with his old friends, The Books, for his project.

But what if you don’t want kids? Those of us who still feel like children—anxious, sensitive, convinced of monsters—don’t necessarily feel equipped or interested in raising others. Among the childless children’s book authors are Margaret Wise Brown, Beatrix Potter, Maurice Sendak, Dr. Seuss, Louisa May Alcott, C.S. Lewis, and J.M. Barrie, who literally “made a career of fetishizing youth with Peter Pan,” as Handy rightly puts it. Maybe never fostering small persons with your genes can arrest you; if you’re not responsible for some other helpless human, you’re forced to linger somewhere in the middle gray, between wriggling larvae and adulthood. Handy admits—perhaps naively—that he doesn’t understand the appeal of Shel Silverstein’s “punishing” book The Giving Tree, the tale of a tree who gives everything to an ungrateful little boy, then perishes as a stump. To me, the book’s popularity is plain: don’t all children guiltily suspect we’ve stolen our parents’ lives? The Giving Tree confirms it’s true.

It makes sense, then, that children’s book writers don’t necessarily want to have kids, but rather to be them. As Wise Brown put it, “To be a writer for the young, one has to love not children, but what children love.” Kids can get over things easily; they forget; they’re not sentimental. Plus they’re often bored, Handy points out: “Childhood is full of longueurs, and growing up can be tedious.” Only adults would write fawning stories of youth extended, animals living peacefully without the threat of poaching, mystical realms where Donald Trump and people like him don’t exist and never will. We have to know how bad the real world can get—the dullness, the endless disappointments, the people who aren’t what we expected—before we’re driven toward escape. “Creative Fantasy is founded upon the hard recognition that things are so in the world as it appears under the sun,” wrote J.R.R. Tolkien in his essay “On Fairy-Stories,” “ . . . so upon logic was founded the nonsense that displays itself in the tales and rhymes of Lewis Carroll. If men really could not distinguish between frogs and men, fairy-stories about frog-kings would not have arisen.”

“Don’t all children guiltily suspect we’ve stolen our parents’ lives? The Giving Tree confirms it’s true.”

Handy sympathizes with children’s authors who find themselves less revered in the literary world than their Serious peers and are frustrated by the demotion. Maurice Sendak grumbled about being relegated to “kiddiebookland,” mourning his missed shot at bookshelf placement near Norman Mailer or Saul Bellow. Indeed, books for children don’t score the acclaim, the Man Booker or Nobel Prizes. They’re wild and unruly and difficult to qualify. “They still retain their rough, strange edges,” Handy writes of fairy tales. “[They] cling to the imagination, like burrs you can’t pry from a sweater.” He believes such stories occupy a kind of “literary danger zone,” comparable to B-movies or pulp fiction. But kid’s books are where I personally learned most everything important about the world: About rape and sinister men from Beatrix Potter’s Jemima Puddle-Duck; about eroticism from Sendak’s In the Night Kitchen; about feminism from P.L Travers’ maverick goddess Mary Poppins; about loss and the unceasing progress of time from E.B. White’s Charlotte’s Web.

During my freshman year at NYU, I entered into a fierce classroom debate over Anthony Lane’s New Yorker piece “Hobbit Habit.” Ahead of Peter Jackson’s trilogy release, Lane had written about the lasting appeal of Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, concluding flippantly: “Boys have traditionally been fonder of it than girls, who are less fazed and flummoxed at the prospect of growing up; women leave their girlhood behind with a glance, whereas men keep looking over their shoulders at the vanishing Shire and asking themselves if it might still be possible, or proper, to head back to their hole in the ground.”

God, that pissed me off. My classmates thought Lane made perfect sense (“Yeah, boys like Star Wars and fantasy more than girls do! And girls always play dress up. Boys want to play with action figures.”) There’s this prevalent though mistaken notion that girls grow up easily, whilst boys resist. As a feminine resistor, I’m insulted. Women have had to become mothers, housekeepers, nurturers—we grew up out of necessity and even via force. Handy is sharp enough to note that women writers like Laura Ingalls Wilder (Little House on the Prairie) and Louisa May Alcott may have felt “obligated” to follow their fictional heroines all the way through to adulthood and marriage, a fate never inflicted on the likes of Mark Twain’s Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn, or on any boy book heroes excepting Harry Potter (whose creator was, non-coincidentally, a woman). Alcott’s editors and eager lady readers didn’t want Jo to remain an unfettered recluse, and the author was unable to shake the pressure. She married Jo off. This adherence to social stricture seems to me cause for pity—not contempt, as Handy implies. After all, sometimes we don’t get to become the sort of person we’d dreamt of being.

From Little Women. Illustration by May Alcott.

From Little Women. Illustration by May Alcott.

But the thing about trying to go back is, you really can’t. I did a two-year stint at a children’s bookstore in a big city, owned by a tyrannical fellow who resembled an overgrown toddler himself. He worked from a desk surrounded by musty stacks of priceless children’s literature and original signed Sendak prints; he was tremendously knowledgeable about all that stuff and horribly nasty to his employees. The temper tantrums were legendary. One of my co-workers compared our bookselling jobs to being “back in the womb,” and it was warm and cozy. We sat around and read all day, with few responsibilities—but none of us wanted to end up like the boss, who never grew up. Though he so deeply loved what children love—books of innocence, wonder, magic—he retained an immature and ungenerous nature that felt out of place amidst all those picture books for sleepy kids.

Handy ends his survey of child lit with E.B. White, whose terse brilliance has yet to be surpassed; he was similarly successful at writing for adults. The grand tear-jerking finale of Charlotte’s Web is technically the spider’s quiet death, but I’ve always struggled most with Fern’s declining interest in Wilbur the pig’s survival. She’s grown too invested in riding the Ferris wheel with a boy named Henry Fussy. White “doesn’t condemn her for it,” Handy notices approvingly, since “Fern’s interest in boys is as natural and inevitable as the change of seasons.” White doesn’t wish to stunt his heroine’s growth like other children’s authors might (C.S. Lewis infamously shamed Susan Pevensie for leaving Narnia behind in favor of lipstick and nylons when she came of age).

I understand Fern’s falling for Henry Fussy. I’ve fallen for more than a few Henry Fussys myself. But her abandonment of unsuspecting Wilbur still hurts me in a way a Henry type never could. I guess it’s the ache of innocence—the kind of ache that doesn’t have anything to do with lust or greed or any dark desire, but with deep-seated childhood fears. I don’t want Fern to leave Wilbur behind, because I feel as though she’s leaving me, moving on from our days of lounging in the barn amongst earthy smells, two lazy friends sat in the sun. At the same time, I know that I am Fern, and I’ve abandoned Wilbur a hundred times over, following the same societal and biological pull of romance and progress. I’ll probably be torn between the two all my life. Maybe everyone is.

Anya Jaremko-Greenwold

Anya Jaremko-Greenwold is a culture writer and the managing editor of FLOOD Magazine in Los Angeles. She is deeply passionate about children's literature.