You Can Hate Leaving Your Child, and Be Glad You Went

“I would be a different kind of mother if I didn’t get on that plane."

This is the story I have dreaded writing.

I have hinted that Alexander was a difficult delivery, that he was born sick. In fact, Alexander was born not alive.

There is a fat white envelope in his medical file that contains the details, an envelope that I had never opened. On the outside it is addressed simply to “Parents”; whoever was writing was too busy to look up our names. Underneath, in a different color ink, I have noted, “Discharge papers from NICU,” the neonatal intensive care unit.

This envelope has rested in our file cabinet, sealed and undisturbed, since the day we brought him home. I don’t remember throwing it in there. I must have been too exhausted to confront yet more hospital paperwork. Nick and I had spoken in person with Alexander’s doctors and nurses; we had follow-up appointments galore scheduled with specialists. We knew he had suffered a stroke. We were focused on his recovery and treatment going forward. What was the point of torturing ourselves by looking back, reading a blow-by-blow account of the trauma that had unfolded on the day he was born?

Somehow fifteen years passed. It was only when I started digging around recently in Alexander’s files, trying to find any documentation I’d kept about his speech therapy, that I found the envelope again. Curious, I tore it open. I naively figured I would flip through quickly, chuck it in the trash bin, and clear some space in the drawer. After all, what could it matter? We had survived this long without knowing what was in there.

The discharge summary begins benignly enough: “Baby boy Kelly is the 2930g product of a 38 1/7 wk gestation. …”

The single-spaced pages are clotted with medical jargon. They describe a mostly non-eventful pregnancy, culminating with my being admitted to the hospital at 5:15 p.m. on a Saturday afternoon, contractions coming every five minutes. So far, so normal.

But from there the account turns dark. “Initial presentation was shoulder, and rotation was attempted,” begins the section titled “Delivery History.” This much I had known before reading. Alexander was breech, and a rare and especially dangerous type of breech, in which he had attempted to join the world shoulder first. The danger is that the shoulder gets stuck, and the mother’s uterus—my uterus—keeps contracting over and over to surmount this obstacle, until the uterus ruptures.

The delivery was further “complicated by nuchal cord x 2,” meaning the umbilical cord was wrapped twice around his neck. They kept trying to rotate him. I kept begging for an epidural. When they lost his heartbeat (“nonreassuring fetal heart tones”), I was wheeled to an operating room for an emergency Cesarean section. The first attempt failed. He was stuck, too far engaged in the birth canal.

The document is focused on the baby, but I had watched as they first split me open from hip to hip, then cut straight up my belly in a jagged, inverted “T” to try to lever him out.

It’s here that my firsthand knowledge of events ends. Somewhere around this point I passed out, either from loss of blood or from pure horror. When I came to, hours later, I was in a recovery room and Alexander was in the NICU. He would remain there, in an incubator, for days. The dispassionate account in this long-forgotten envelope marks the first time I have learned specifics of the actual delivery.

“Patient was transferred to the warmer without respiratory effort, completely limp,” it states. “Color initially noted as uniformly gray.” Soon after, “there was one failed attempt at intubation.”

The most devastating section, the one that causes my eyes to prick with tears all these years later, is titled “APGARs.” The Apgar is a test given to newborns. It measures five things to check a baby’s health: skin color, heart rate, reflexes, muscle tone, and respiration.

A perfect score is 10.

Alexander’s, at one minute after delivery, was 0.

Zero.

No pulse, no response, not breathing.

My hands are shaking as I read the contents of the envelope, shaking as I type this now.

Which is intriguing, because there’s no actual suspense here: I know how this story ends. Indeed, things start to look up even before the end of page one. Something called a BVM, a bag-valve-mask resuscitator, appears to have been crucial. Several minutes after delivery—exactly how many minutes is not clear—Alexander starts to fight to breathe. He is “stimulated vigorously” and CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure) is initiated, to try to keep his airway open. He falters, then keeps fighting. Things could go either way.

His length is “not yet measured”; there’s been no time.

“Irregular respiratory effort” is noted, as are “improved color, tone.” They suction. More CPAP. By ten minutes after delivery, his Apgar score has soared to 7. Seven! Was there ever a more wondrous number in the history of numbers?

The “Delivery History” section closes with Alexander being transferred to the NICU, CPAP still in progress en route. Upon arrival, an IV is established. His blood pressure and head circumference are recorded. His length is “not yet measured”; there’s been no time.

The comment that I keep running my finger over, the one that would have given me hope had I been conscious during those awful minutes, is this: “Good tone, pink all over body, strong cry.”

Strong cry. Yep. Sounds just like him. My boy. He made it.

Nothing about the days that followed was easy. I was weak and listless and would remain so for a while. We were permitted to visit the NICU but not to lift Alexander from the incubator. I was not allowed to hold him, not allowed to breastfeed.

In later sections, the discharge file discusses his stroke. “MRI on DOL 2 showed: ‘Small, recent stroke at the border of the right thalamus and posterior limb of the right internal capsule,’ ” it reads. “The lesion measured approximately 6mm.” In the hospital, they performed all kinds of tests trying to figure out what had caused it. Neither those test results nor any of the myriad pediatric neurology appointments in the months that followed revealed a satisfying answer.

No one has ever been able to tell us how long Alexander went without a pulse, how long his brain had starved for oxygen. And we’ve never learned what was the cause and what was the effect. Did the stroke occur in utero and somehow contribute to his nightmare delivery, or was it the ordeal of his nightmare delivery that somehow caused a stroke?

These felt like urgent questions for a long time. They came into play when his speech was delayed. They flickered in my mind when he tripped, banged his head on concrete, and knocked out his front teeth at his third birthday party. And when he spiked a fever and a chest infection serious enough that the school nurse had occasion to track me down in Iraq. But as he grew and thrived, they loomed smaller. Whatever had happened at the border of the right thalamus and posterior limb of his right internal capsule … whatever injury his tiny head had sustained … it had healed.

The neurologists eventually gave us the all clear. They could find no indication of lasting brain damage. No indication of anything other than a healthy kid. After a while I started writing “N/A” or “none” on routine health forms for sports and school when they asked about any significant medical history. None of this seemed like information that a summer camp counselor, about to instruct my son on how to pitch a tent or paddle a canoe, needed to know.

As I write this, Alexander sits upstairs in his bedroom at his desk. He is healthy. His skin glows pink and his heart beats and he breathes—in and out, over and over, without even having to try. His only cause for distress at this precise moment is an overload of Spanish homework. From the top of the kitchen stairs, he calls down: Will I come drill him on the difference between ser and estar? Also has anyone walked the dog? Also what’s for dinner? I call back that I’ll answer him when he asks me all this in Spanish.

It is difficult to reconcile the pages I have just read with the boy upstairs. They seem to chronicle an ancient history, one best folded away again and forgotten. But they are not irrelevant, not quite. First, because they cause my heart to fly out to the parents of children whose stories have a different outcome. The pain must be unending.

And second, they force me to think about the unthinkable.

I had known he was born sick. I had known—you had only to look at the ridge of scars bristling across my stomach—that his delivery had been far from ideal. But I had not fully understood, not until seeing my son reduced to a score of zero, how very close we came to losing him. I want to race upstairs, fold him in my arms, and never let him go. If I had known, if I had opened and read this envelope years ago, would I have let him out of my sight?

Would I ever have left that little boy’s side?

Because I did, so many times.

The trip that stands out in this regard was to Pakistan, in 2006. I traveled to Islamabad and its twin city, Rawalpindi, then drove west to report from Peshawar and the Afghan border. The intelligence beat, then as now, involved trying to track the CIA, the NSA, and other spy agencies. This means paying attention to whatever they’re paying attention to. In 2006, it boiled down mostly to two portfolios: terrorism and rising nuclear threats. The two converged in Pakistan.

“Pakistan has more terrorists per square mile than anyplace else on earth. And it has a nuclear weapons program that is growing faster than anyplace on earth. What could possibly go wrong?” Those are words I wrote for a fictional CIA officer to deliver in Anonymous Sources, my first novel, the one about an intrepid reporter named Alexandra James. I was able to write the lines with some confidence, drawing on my own reporting trips to Pakistan.

On the one in question, I had sat inside the headquarters of Pakistan’s Inter-Service Intelligence agency, the ISI, and questioned the generals who ran it about allegations of links to the Taliban and Al Qaeda. They blew smoke rings above my head and denied the allegations. I sat inside the headquarters of the Strategic Plans Division, the SPD, and questioned the general in charge of Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal about whether the weapons were locked down and safe. I don’t remember if he blew smoke rings; I do remember what he said: yes.

Both the answers to my questions and the overall security situation grew less predictable outside the capital. My interpreter, a young woman from the country’s troubled tribal areas, had for several days been by my side, helping me conduct interviews with her hair uncovered, earrings and necklaces flashing. But I remember the moment we left Islamabad and turned onto the Grand Trunk Road to make the two-hour drive to Peshawar. She fished a head scarf from her bag, wound it tightly to cover every feature but her eyes, and advised me to do the same. “Always, outside Islamabad,” she whispered.

We stopped along the way for tea and fruit with the leaders of the Akora Khattak madrassa, the famous religious school where many members of the Taliban had studied. We drove through Afghan refugee camps and then high into the mountains of the Khyber Pass.

It strikes me now, from a personal security perspective, as a pretty dumb thing to do.

Another day, my interpreter took me to her family’s village. We passed checkpoints to get there—many parts of the tribal areas were and remain no-go areas for foreigners and even for the Pakistani army—but we met no resistance. Men wandered up from their work in the sugarcane and tobacco fields and crowded around us. I asked about 9/11, and about bin Laden, whose whereabouts were then unknown.

“Osama can go to hell,” one old man spat.

We stood in a muddy paddock and interviewed him and others until twilight fell, without a guard, without a cell phone, without having told anyone back in the office where we were. It was a phenomenal day of reporting. It challenged me to think more deeply dysfunctional country with nuclear weapons, North Korea, about the complexities of the U.S.-Pakistan relationship. And it strikes me now, from a personal security perspective, as a pretty dumb thing to do.

The other thing that strikes me, as I comb back over NPR transcripts to recall who we talked to and where—is when this happened. I was away in Pakistan for the first two weeks of November 2006. James was three years old. Alexander was not yet 13 months when I left. He was not yet walking. Hmmm. It occurs to me that I would think carefully even today, with my children nearly grown, before leaving my family to jet off for two weeks on assignment to—as a colleague based in Islamabad once described Pakistan—a “dysfunctional country, in a dangerous neighborhood, with nuclear weapons.”

Do I regret going?

God, no.

Sharpen it to a more uncomfortable question: Do I regret having gone, now that I understand that Alexander had very nearly died only months before?

The answer, honestly, is still no.

And not just because he was totally fine, well cared for in my absence, and still crawling when I returned. I would be a different person, a different kind of mother, if I didn’t get on that plane. Of course I would have hated it if I’d missed his first steps. But he would have been wriggling out of my lap even if I’d stayed. Squeezing him tight in my arms and never letting go—that was never an option, was it? Our children are outgrowing us from the moment they are born. You can let a lot of life pass you by, sitting at home, waiting for people to need you.

Tweak the question about regret by just a word or two, though, and the answer changes. I do not regret going. But do I regret leaving him? Yes. God, yes. Always. Still.

More than a dozen years later, as I departed for another dysfunctional country with nuclear weapons, North Korea, I lingered at the door. Nick and the boys were inside the house, pottering about, debating whether to grill or order pizza for dinner.

I tried to put words to what I felt. From the back seat of the car to the airport, I wrote the following on Twitter: “That moment, no matter how big your children get, when you’re leaving on a long work trip & the taxi pulls up and your kids hug you & you just want to cancel the whole thing and go back inside & build a pillow fort instead.”

Every damn time.

Before I left for that 2006 trip to Pakistan, I taped a piece of pink construction paper to the door in James’s bedroom. At the top I had glued a recent photo of myself, sunglasses pushed high on my head, smiling back over my shoulder. Beneath was a hand-drawn calendar, 14 neat boxes. One for each day I would be gone. Inside each box was a smiley face or a heart or a short message (“Big kisses!” “Halfway done!”). The idea was that the boys would be reassured if they could keep track of my trip, by counting the days and crossing a big “X” over each one until Mommy came home.

I harbor deep suspicions that neither of them ever touched it. It must have been either the nanny or Nick who hastily crossed off every box, likely as I made my way back home from the airport, so I wouldn’t get my feelings hurt. The Xs are too uniform, relentlessly within the lines. Not at all what a one-year-old or a three-year-old handed a black felt-tip pen would produce. I feel a pang of gratitude to whichever adult made that effort, followed by a pang of gentleness toward myself: I was trying so very hard.

Back in 2006, I had not yet grasped how fleeting a privilege it is to make a calendar like that. To believe that you stand so utterly at the center of another person’s universe that they might care to count down the days, one by one, until you come home to them. Whereas if I were to travel tomorrow? My husband loves me, but he’s not going to require a pink construction paper chart to survive two weeks without me.

My teenagers love me, but ditto. My mother? My brother? My oldest, dearest friends? They would be fine with exchanging a flurry of pre-departure texts: “Have a great trip! Good luck! Stay safe!” I wish I could go back and tell myself, Treasure this. Treasure the way their eyes light up when you walk into a room. Treasure even the mornings they cry for you, the ones when you have to unwind and tear their arms from around your neck as you leave. Never again, I would tell my younger self—never again will someone need and love you with the intensity that James and Alexander do, right now.

I said that I dreaded writing this story, and I did. It is not easy to read or to write an account of your child in pain, even when the events in question are in the past tense and long ago. But corollary to the fact that you can’t be in two places at once—that not one of us, not a single one, has figured out how to be on the Khyber Pass and be home building pillow forts at the same time—runs another reality.

It has to do with how two competing ideas can coexist. How two contradictory thoughts can both be true. Do I regret going? No. Do I regret leaving my babies? Yes.

I speak from personal experience when I say that the following holds true, whether children are newborns or nearly grown: it is possible both to hate leaving them, and to be terribly glad that you went.

__________________________________

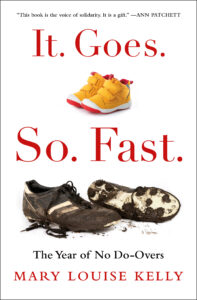

Excerpted from IT. GOES. SO. FAST.: The Year of No Do-Overs by Mary Louise Kelly. Published by Henry Holt and Company. Copyright © 2023 by Mary Louise Kelly. All rights reserved.

Mary Louise Kelly

Mary Louise Kelly has been reporting for NPR for nearly two decades and is now cohost of All Things Considered. She has also written suspense novels, Anonymous Sources and The Bullet, and is the author of articles and essays that have appeared in the New York Times, The Atlantic, Washington Post, and the Wall Street Journal, among numerous other publications.