Falling in Love with a Dog and the World

Ramona Ausubel on the Softness of Beasts

An article popped up on my screen: scientists plan to bring back the woolly mammoth. I started writing because this seemed like the kind of human folly perfectly suited to a novel—hubris plus hope plus infinite unintended consequences. The mammoth in my book was incidental because I was focused on the scientists and their relationships with each other and the world. I was focused on human folly and human hope.

Then I got a dog. Olive came from the puppy emergency that was the pandemic but the rescues she has performed have been many. My kids fawn over her every day, no matter what the seas of pre-teen-ness bring. Recently Olive led me home on a walk when my vision disappeared with a migraine. When someone went into a grocery store a few miles from my house and killed eleven people, I lay on the floor next to Olive and smelled her paws and rubbed her warm belly and tried to believe in goodness. When a wildfire caught a spark and spread quickly through our town I catalogued all the potential losses in our home and accepted the possibility of them because my family and my dog were safe.

I kept writing about the scientists and their attempt to use CRISPR technology to edit an Asian elephant cell to look more like a woolly mammoth cell (birth by revision—familiar territory for a writer). I wrote about the steel and glass lab, the politics, the unintended consequences of making a new creature and dropping it into the world. But pretty soon, with the dog asleep on the couch next to me, my book started to paw at me to ask for a real, living animal. Not a hypothetical, not the idea of an animal but the warm gift of a four-legged, warm being.

Her name is constantly in our mouths.The novel is still about gene editing and science and extinction but it is also about being a (human) animal. In it, there now lives a very real-to-me woolly mammoth. She is born in the shade of a grove of oak trees on the shore of a famous Italian lake. She has scrappy tufts of hair and one tiny, buried tusk, which is the origin or her name: Pearl. The more I wrote, the more the animal, which had been called forth out of the characters’ scientific ambition, became something they loved, and her safety became a wish they kept on whispering in the dark. She is not a project but being, and her presence changed the relationship between the book’s mother and daughters and between the two sisters. The mammoth is not only matter, but matters.

The dog is asleep on the couch next to me while I type, her paws bundled into a bouquet. She has recently had a haircut and her fur is especially soft and I can feel her breath against my leg. Her eyes twitched in a dream—is she running through a field full of rabbits? Does she dream in pictures or in smells? She is so familiar to me, and so outside of me. You might call that love.

The first time we met Olive it was in the parking lot of a Wal-Mart two hours from our house. The four of us stood close while a friendly man reached into the back of his truck and pulled out a tiny, fuzzy bundle and handed her to me. I sat in the backseat flanked by my two children while my husband drove, and we all cooed and fell in love. It was in the early days of the pandemic when no one was going anywhere and huge signs on the highway warned us to stay home unless it was essential. Essential, yes, that’s a good way to describe this feeling, I thought.

Olive made our foursome into a quintet and the new element was not only physical but an almost audible joy. Her name is constantly in our mouths. If ever any child is grumpy I only have to tell them how the dog slept on my head last night, or how she got surprised by a flock of chickens in someone’s backyard on our walk, and the bad mood cracks. Frequently one family member enters the room another is in and says, “You have to come in here and look at Olive. She’s so cute.” In the frequency of our family there is hum, high and happy, of three humans sharing their lives with a beast.

We think and imagine but we also burrow close in fear, we need a warm body to help us process grief.The scientists and their intellectual pursuit are still present in The Last Animal. The human mind and its particular hunger is still present. What the baby mammoth reminded me, what the dog reminded me, is that we humans are an animal too. We think and imagine but we also burrow close in fear, we need a warm body to help us process grief. We are delicate and mortal and soft. The closer we are to that truth, the more honest we are. The better.

Pearl, the woolly mammoth is not a prop. She is not a science experiment (or only one). Her presence is warm and living and she reminds the humans in the novel that care is required, care is non-negotiable, that they all live in fragile, miraculous bodies and are each other’s only keepers. She made them back into the people they had forgotten how to be.

Olive puts her face on my knee and the sun catches her ridiculously long eyelashes. She’s ready for a walk. I have been writing all morning it’s time for a break. Both of us animals need to move, to find out what the world has made today.

Some artists have a gorgeous female muse rising out of a clam shell; mine has curly fur the color or butter and brown ears and she sneezes when she’s excited. She knows what’s good on this earth. Her powers are infinite.

__________________________________

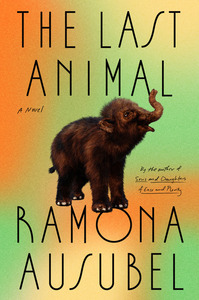

Ramona Ausubel is the author of The Last Animal, available now from Riverhead Books.