You Are Being Lied to About Gaza Solidarity Camps by University Presidents, Mainstream Media, and Politicians

What Steven W. Thrasher Saw on College Campuses

Saturday was a gloriously beautiful spring day in Chicago, and as I wandered into the “Liberation Zone” which has taken over DePaul University’s quad, a kind lady asked me if I would like some lunch.

I declined because I was headed to a BBQ in a couple of hours, but I took her up on some coffee, thanked her, and asked her if she was affiliated with the Vincentian Catholic university.

“No,” she told. “I’m just Palestinian.”

I recognized her from previous visits to that particular Gaza Solidarity Encampment, one of four I have visited over the last few weeks: Columbia University’s (where, as a PhD student at NYU, I once took some classes), Northwestern University’s (where I am on the faculty and am a member of Educators for Justice in Palestine), and the University of Chicago’s (where, like at DePaul, I was there to observe and to offer faculty de-escalation support if needed). The lady had been at DePaul every day, serving free food (often donated by Palestinian restaurants) to hundreds of people.

She, like everyone there that day, was extremely welcoming.

Over the previous few days, I had gone to bed or woken up to dark, war-like scenes of unspeakable violence waged by police and state troopers who were often wielding machine guns, lobbing chemical weapons, and shooting rubber-coated bullets (and at least one naked bullet which was not coated in rubber). Though some of the police raids happened in daylight, most have happened at night, with projectile-gun blasts and flash bangs lighting up sinister spectacles of utter chaos.

Those scenes were such a contrast to DePaul’s Liberation Zone, which was almost placid on Saturday. Pivoting from the kind woman offering lunch, I saw a local musician teaching a group of students how to drum quietly on plastic Home Depot buckets. At the art tent, people were making signs. Many students were sprawled out on the grass, lazily enjoying the sun while reading books, writing, drawing, or debating politics. This seemed to be not only exactly what college life should be—judging from the official DePaul sign on the student center saying “Here, we hang out with a purpose”—it looked like what this university in particular desired.

The only violence came from Zionist counter protesters and, to a much larger degree, the police.

Indeed, at all four camps where I have spent time, I have been blown away by the light, the grass, the sky, the spirit of generosity, the easy temporal nature of camping with friends, the camaraderie, and—for the modern American university—the surprisingly religious spirit (drawn from Islam, Christianity, Judaism, and Native American traditions). These encampments were not always calm—sometimes they could be quite lively—yet they were among the most dynamic, electric, alive and pedagogical spaces I have ever seen.

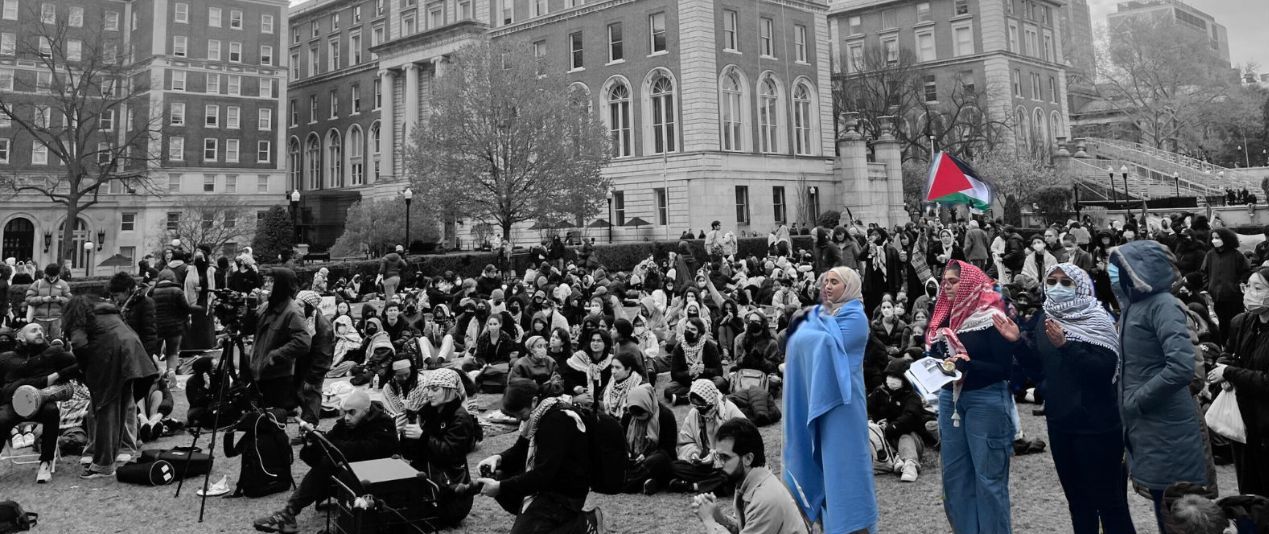

Between salah and shabbat prayers, students at Columbia’s encampment listen to a speaker at sunset. April 19. All photos by the author.

Between salah and shabbat prayers, students at Columbia’s encampment listen to a speaker at sunset. April 19. All photos by the author.

But violent? The only violence came from Zionist counter protesters and, to a much larger degree, the police. The cops are the chaos agents which make these lovely, often gentle spaces into brutal hellscapes.

Feeling the gentle breeze and the sun on my skin as I floated around DePaul’s camp, I thought about how lucky I am to travel between these sights.

But to those of you who haven’t been able to get to a camp, I say: You are being lied to about these spaces—by most reporters, by most politicians, and (with extremely few exceptions), especially by university presidents.

*

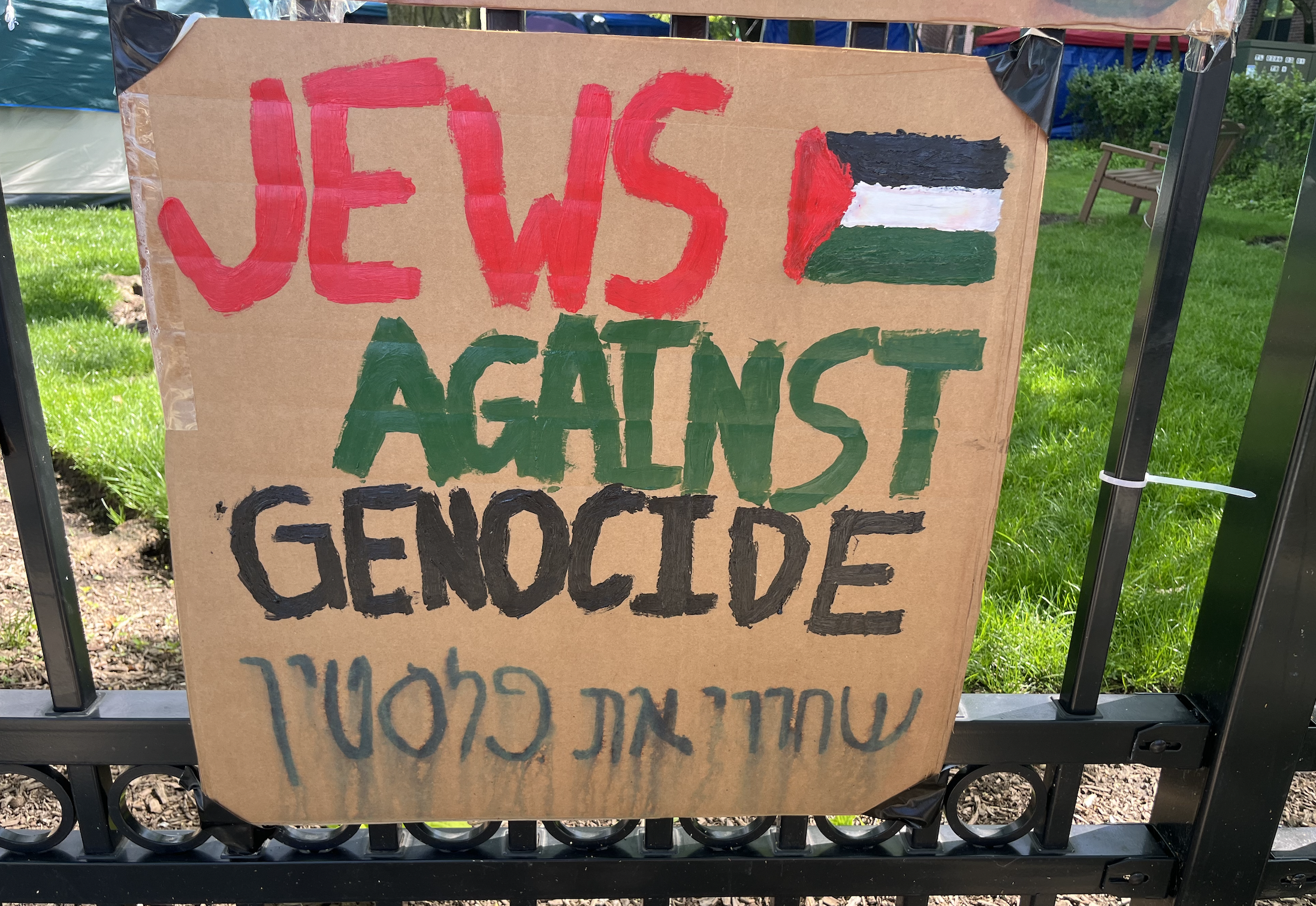

One of the lies you have been told the most is that these encampments are antisemitic. It’s scurrilously perpetuated by journalists like CNN’s Jake Tapper, who are “reporting” from WhatsApp group chats, as well as by politicians, from Republican Speaker Mike Johson to President Biden.

I visited Columbia’s Gaza Solidarity encampment on Friday April 19, a day after the first police raid arrested 113 people and a new set of tents took over the southwest corner of the quad. One of the first things I saw made it apparent to me that early reports of religious strife were just moral panic. A group of Muslim students were kneeling in prayer and, in a scene I have since seen recreated at different camps, a group of students—many Jewish— held a tarp up around them to give them privacy. (Later that evening, Jewish students hosted a seder on the lawn.)

The view from inside Columbia’s encampment, looking towards Low Library, April 19.

The view from inside Columbia’s encampment, looking towards Low Library, April 19.

I also observed a group of speakers address the camp, including a Palestinian American nurse who had recently returned from a shift in Gaza, a white woman who had been arrested in that same spot in 1968 and, most controversially, Norman Finkelstein. Finkelstein is an uncontested expert on Gaza, but he is on the wrong side of some social issues for many students and he does not like the phrase “from the river to the sea.”

And yet, in a scene that should have made contrarian “free speech” diehard contrarians happy, the students listened to all the speakers respectfully. Even when Finkelstein welcomed criticism, it was given, and received, respectfully. (And when he left the lawn and the students chanted “from the river to the sea, Palestine will be free,” he laughed with good nature.)

What I witnessed at Columbia is what I have seen at all the encampments (and, similarly, in years prior, at Occupy Wall Street at Black Lives Matter encampments): students experimenting with making a society better than the shit one they’re expected to accept, enter and recreate. They were experimenting with self governance and horizontal organizing. They were experimenting with educating, entertaining, feeding, defending and (quite unusual at elite universities) praying for and with one another. They were figuring out their values, and putting real effort into trying to do what’s right. How beautiful is that?

Students and elders were sharing their religious traditions and experiences, in a common cause of love and justice to combat American empire.

University administrators want to control every single aspect of students’ social lives, such that they can only produce a limited, finite set of outcomes: one where students will not question the ruling class, but will only socialize in ways that reproduce the social order, and only socialize in ways which maximize profits for the ruling class and uphold the aims of American empire.

Stray from that and you will be destroyed.

And that’s why you are being lied to about these encampments.

*

On April 30, the following Thursday, a few dozen Northwestern University students declared Deering Meadow to be a Liberated Zone. (It was a fitting location, given the lawn was dedicated to the six student protesters killed in 1970 at Kent State and Jackson State Universities.)

As a member of the group Educators for Justice in Palestine, I signed up as a faculty supporter. We made sure there were always at least four faculty on site with the students, to liaison with police, talk to administration or—given the horrific beatings we had seen the day before at the University of Texas Austin and University of Southern California—to physically intervene if needed.

I was on the first shift when the camp began. It was a bit chilly, but it was a totally serene scene and a beautiful morning—bucolic, even. Students were putting up tents, preparing to serve food and laying out literature which represented their hopes and dreams for stoping the genocide and making a better world. I could hear birds chirping. I saw a bunny.

Students relaxing on the first day of Northwestern’s encampment, shortly after the police retreated, April 25.

Students relaxing on the first day of Northwestern’s encampment, shortly after the police retreated, April 25.

But then a helicopter buzzed in and, unlike at any other university which I have seen, Northwestern’s police showed up immediately. Within minutes, they threatened to arrest our students.

My colleagues and I hastily formed a faculty defense line, arm-in-arm. The police moved in, pushing, kicking and beating us. A man who identified himself as Northwestern’s Chief of Police (and who is also a “Senior Associate Vice President of Safety & Security”) attacked me personally. It was a harrowing and physically painful experience (and I developed a pain in my right hip still bothering me two weeks later.)

I was deeply touched as matzoh was passed around and folks wearing yarmulkes and hijabs alike literally broke bread with one another.

But, after being jostled around for some time, we prevailed. We held the line, we kept the police from hurting our students, and the cops retreated (to great applause). The camp was born and, for the next five days, Northwestern’s Gaza Solidarity Encampment turned our campus into a welcoming space for students, faculty and neighbors.

A sign on a student’s tent at Northwestern University, May 26.

A sign on a student’s tent at Northwestern University, May 26.

And like all acts of camping, the Liberation Zone allowed people to have a different relationship to time, nature, and to each other.

The life of the camp coincided with the Jewish Passover holidays, and the lie of antisemitism was powerfully burst at every sundown. Each evening would begin with a Passover Seder, as Jewish members of the community lit candles, shared the story of Pesach, explained the foods, and shared the prayers. I have never been more proud of a former student then when one of mine got up on the mic, explained what her Jewish faith meant to her, and spoke passionately about how the lesson of the holiday mean that “never again” meant never again for anyone—in Gaza, Congo, Sudan, America, or anywhere.

I was deeply touched as matzoh was passed around and folks wearing yarmulkes and hijabs alike literally broke bread with one another.

On Friday night, with hundreds of people in attendance dressed in keffiyehs, the encampment’s Jewish community taught everyone to sing the Hebrew song of gratitude “Dayenu.” As a Christian, I had learned this song some 20 years ago at my first seder. But in the secular setting of our university, hearing hundreds of people singing Da-ay-enu, da-ay-enu, day-ey-enu, dayenu dayenu together—as Jews, Muslims, Christian, Hindus, people of Native American faiths and no religious faith at all—was one of the most special moments of my life.

That same evening Bethy Massey, an elder who had been at the Columbia protests in 1968, addressed the crowd. Despite her soft voice and pronounced tremor, hundreds of young people listened in rapt attention.

Northwestern students gathered for Friday Shabbat prayers and community talks, April 26.

Northwestern students gathered for Friday Shabbat prayers and community talks, April 26.

This sharing of the Passover meal and intergenerational communion were not, of course, antisemitic—just as the issue of colonial domination in Israel is not about Judaism, or even about religion. These students and elders were sharing their religious traditions and experiences, in a common cause of love and justice to combat American empire.

And that’s why you are being lied to about the nature of these camps, by presidents of universities and of the United States alike.

*

A lie from journalists is that these protesters’ demands aren’t clear, and that the camps are impossible to report on.

On Tuesday, media critic Brian Stelter tweeted this quote from an article by Jill Filipovic: “Despite all the coverage of the protests over Israel’s war in Gaza, it can be remarkably difficult to understand what the players are actually saying.” The article is titled “Say Plainly What the Protesters Want” and Filipovic was not done any favors by Stelter or whoever wrote her headline.

Though I still do not agree with her on much in it, the article is not as flat as the former CNN media critic or the Atlantic headline writer make it out to be. Still, Filipovic begins her essay with the line Stelter highlighted, and its faulty premise: that where protesters stand is confusing. (She herself later writes “the protests—both on college campuses and those led by broader, non campus groups—have articulated demands and ideologies. News outlets have a responsibility to report what those are, and are largely failing.”)

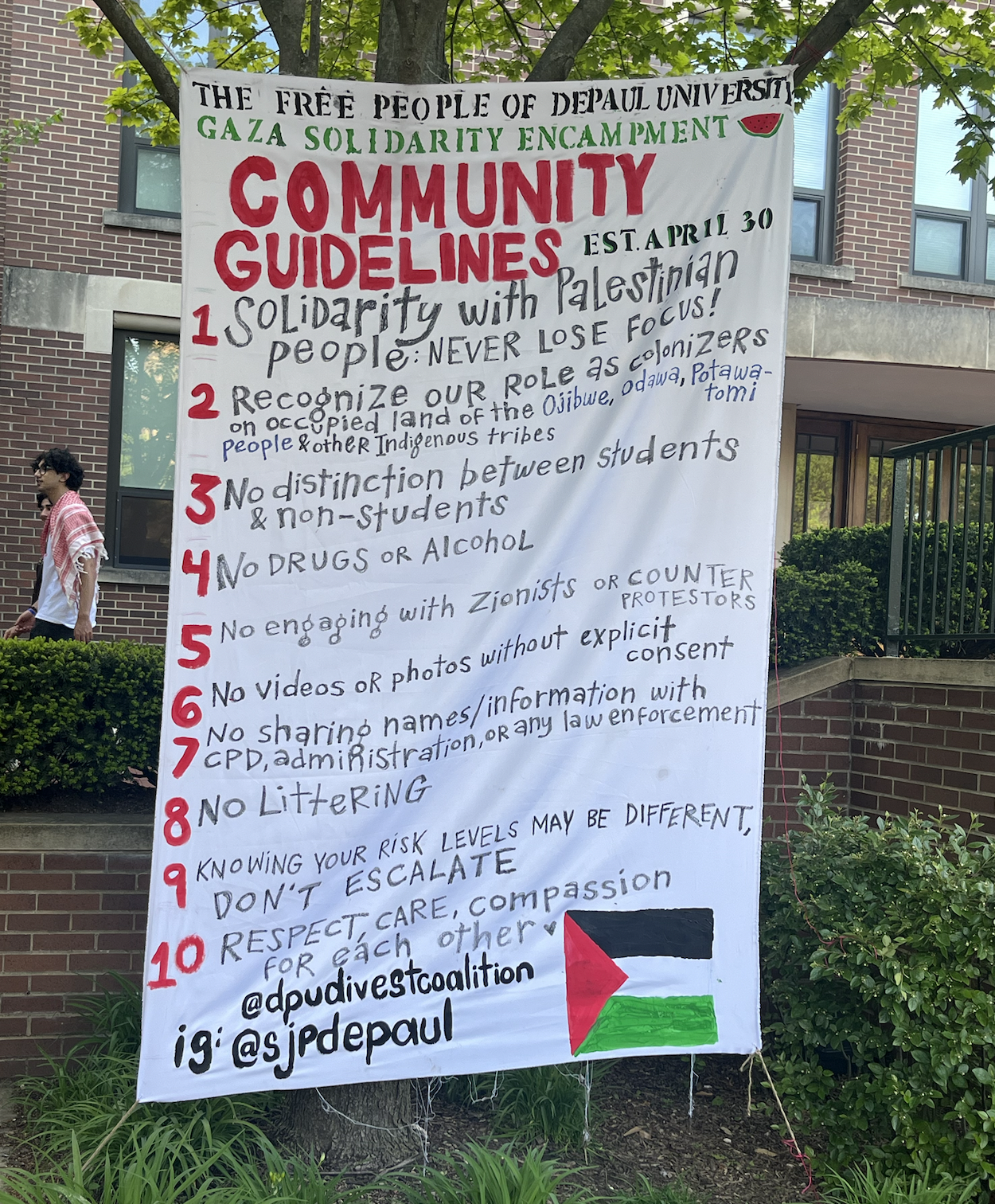

It is extremely easy to see what the students want: the website Students 4 Gaza lists a map of every school encampment (183 as of this writing) and links to each one’s demands. What exactly they want is very articulate, well reasoned, and is as easy to comprehend as signs or chants that say Disclose! Divest! We will not stop, we will not rest!

The painted “Community Guidelines” of the DePaul Liberated Zone. Students would recite them whenever sessions were held on microphones and ask everyone to agree to them if they were going to be in the encampment, May 1.

The painted “Community Guidelines” of the DePaul Liberated Zone. Students would recite them whenever sessions were held on microphones and ask everyone to agree to them if they were going to be in the encampment, May 1.

But too many journalists perform a particular kind of false, learned helplessness about Palestine, acting like “It’s just too complicated!” when it is not.

No example of this in the past week has been more glaring than Peggy Noonan’s. As she infamously wrote in the Wall Street Journal, she went to the encampment at Columbia before it was shut down for a second time:

I was on a bench taking notes as a group of young women, all in sun-glasses, masks and keffiyehs, walked by. “Friends, please come say hello and tell me what you think,” I called. They marched past, not making eye contact, save one, a beautiful girl of about 20. “I’m not trained,” she said. Which is what they’re instructed to say to corporate media representatives who will twist your words. “I’m barely trained, you’re safe,” I called, and she laughed, and half-halted. But her friends gave her a look and she conformed.

It’s not hard to hear what the students are saying, even if they don’t give you an exclusive scoop. Journalists could just go to a camp…

To her credit, unlike many journalists, Noonan actually went to an encampment before writing about it. But she misrepresented herself (she is not “barely trained” as a journalist), she insulted her would-be sources in the pages of her paper because they declined to talk to her, and she barely tried to listen to them.

Did she try 10 more students?

Did she go to the media table or tent and ask to speak to a student representative?

Did she in any way make herself a helpful member of the community?

More fundamentally, has she lived her life in such a way that an activist upset with the state of the world would want to talk to her? I am guessing the one-time Ronald Reagan speech writer has not. (And, my reading of her career is that she engages in transactional journalism, while many people at the encampments believe in relational journalism.)

A statue on DePaul’s campus of St. Louise who was co-founder, with Saint Vincent de Paul, of the Daughters of Charity. She has been draped with a keffiyeh, May 1.

A statue on DePaul’s campus of St. Louise who was co-founder, with Saint Vincent de Paul, of the Daughters of Charity. She has been draped with a keffiyeh, May 1.

I have never had trouble talking to anyone in any encampment. When I went to Columbia’s, I saw a young Black woman de-escalate a situation with two Zionist students, who were beginning to taunt Muslim students as they prayed. She de-escalated them so deftly, the Zionist students walked away not seemingly out of anger or frustration, but from an acceptance to not bother their fellow students.

When I congratulated her on how well she’d done, we started chatting. Without my asking, she invited me onto the main lawn, which was only for students or their invited guests, and told her peers I was fine to join them.

I hadn’t barked “tell me what you think” at her, nor was I even trying to get closer to the action; the invitation just came organically as we spoke.

Similarly, I visited DePaul last Sunday morning, and the scene was not as relaxed as it had been the day before. Rather, hundreds of students were defending the camp and heatedly facing off a counter demonstration of Zionists. Yet when I walked up to them and asked if I could step inside past their locked arms, I was immediately ushered in. (I later stepped back out when it became clear I needed to pitch in as faculty to help de-escalate the tension and be a police liaison.)

A sign on a student’s tent at Northwestern University, May 26

A sign on a student’s tent at Northwestern University, May 26

New York Times White House correspondent Peter Baker did Noonan no favors when he quoted Noonan’s lines above on Twitter, adding, “When protests are not about actually explaining your cause or trying to engage journalists who are there to listen.”

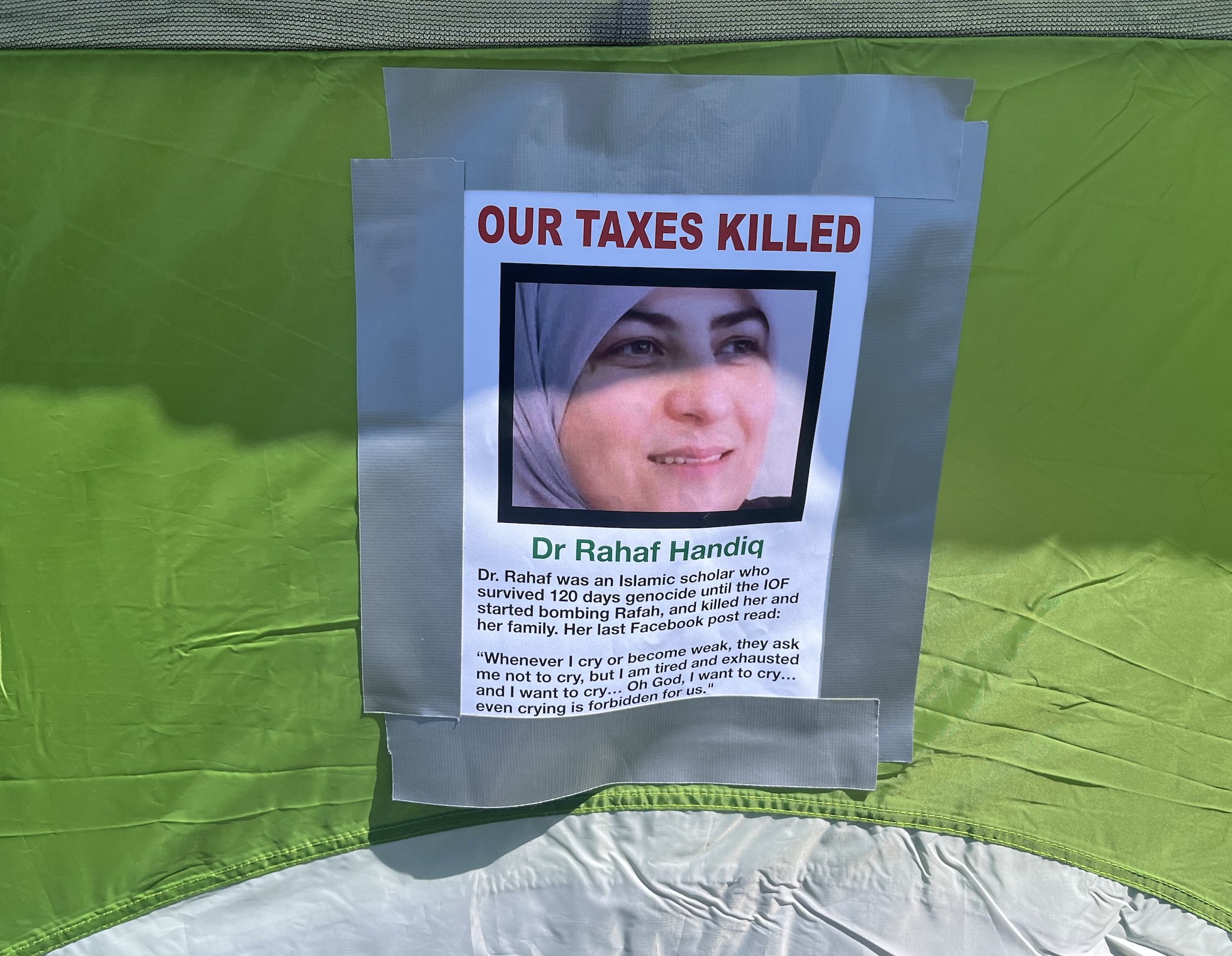

But is Noonan listening to students? Are Baker, Filipovic, Stelter or Tapper? Local journalists are—consider this week’s viral video from the local Fox affiliate TV station with the brilliant University of Chicago student as they fended off police, or this, of a student representative speaking at the Oxford encampment—but are any national journalists listening? It’s not hard to hear what the students are saying, even if they don’t give you an exclusive scoop. Journalists could just go to a camp, talk to the official reps, read the community guidelines, or even just look and listen to the signs around them—like the one made by the student which listed their 200 family members who have been killed in Gaza.

In these contemplative, dynamic spaces, it is not hard to hear what the students are expressing—and sometimes, those expressions are loving and profound.

For instance, the first time I went to the University of Chicago’s encampment in the daytime, I noticed the medics were working out of the Dr. Hammam Alloh Medic Tent. I recognized the name but couldn’t place it from memory, and looked him up.

Dr. Alloh was a sole nephrologist in Gaza, worked at Al Shifa hospital, and refused to leave his patients. As he told Amy Goodman on October 31 last year, even though he and his colleagues were “being exterminated,” he said, “If I go, who treats my patients? You think I went to medical school for 14 years so I can only think about my life and not my patients?

“This is not the reason I became a doctor.”

Less than two weeks later, he was killed by US-backed Israel. He was only 36.

Without even having to talk to anyone at the UChicago camp, I heard what they were about, and what they were saying. Theirs was a message of love, of kindness. Quietly, gently, but in word and deed, they were recovering Dr. Alloh’s spirit of generosity and bringing it back to life—as the students are doing with their Refaat Alareer libraries.

Anyone visiting the camps can see and hear these messages. They are everywhere.

Anyone not hearing and reporting them is lying to you.

*

On Tuesday, my good friend Prof. Eman Abdelhadi, a professor at the University of Chicago, traveled to her students’ camp after midnight. There were credible reports from reliable media sources that a raid was imminent. Prof. Abdelhadi cares deeply for her students, and stayed with them until around dawn, when fear of the raid seemed over.

But, shortly after she and legal observers left, the university’s own police force moved in and raided the camp. Just back home, Prof. Abdelhad returned to campus again.

University of Chicago Police in riot gear standing between the campus Gaza Solidarity Encampment and Zionist counter-protesters, May 3.

University of Chicago Police in riot gear standing between the campus Gaza Solidarity Encampment and Zionist counter-protesters, May 3.

Sharing an email about her university’s “cleanup” of the quad (which terrorized sleeping students and violently destroyed their property), she wrote: “By cleanup they mean destroying the only real community space that’s existed on this campus.”

The shared goals of these encampments—to divest from an apartheid state and end the genocide in Gaza—are not anything to be ashamed about.

“For many of us,” she continued, “these past 8 days were a glimpse into a different kind of life. One where we are truly connected to each other, where we share space as human beings not just as positions (student, professor, etc). That feeling is bigger than a tent, and it will guide us forward.”

This hit me hard. In the five days of my university’s camp, I met more students and faculty (especially people of color) than I had in the previous five years. Outside of my classroom, the Liberation Zone marked the only five days I have felt welcomed or connected to people anywhere on my campus.

I’ve also met more caring, compassionate colleagues at their camps than in any other venue over my years in Chicago. The shared goals of these encampments—to divest from an apartheid state and end the genocide in Gaza—are not anything to be ashamed about. They are moral and righteous desires. Nor are these fringe positions; they are desired by the majority of the people on this planet.

In the four encampments I have visited, it has felt so good to not have to pretend—as so many universities, publications and politicians seem to want us to—that everything is fine and we must just get back to normal by pretending what is happening isn’t happening. Everyone knows police could come in at any second and beat the shit out of them; but they know what’s happening in Gaza is far worse, and so they’re willing to take the risk.

As a professor, it has felt good to pick up trash with my students, and to learn about how to roll a keffiyeh or sing Pesach songs with them. For all four encampments I visited erased a lot of divisions: between young students and old teachers; between faculty and staff; between Jews, Muslims and Christians; between formal members of a university community and our neighbors; between students of different universities (and their peers who don’t go to college).

Like the the Poor People’s Campaign Martin Luther King was planning when he was killed in 1968 (which was supposed to be a shanty town encampment of white, Black and Chicano poor people on the National Mall) the Gaza solidarity encampments have been a taste of what might be possible when everyone freely gets what they need—and when people unite across divisions to share shabbat, salah, and a demand to end war.

And that’s why, so often, you are being lied to about them.

Steven W. Thrasher

Steven W. Thrasher, PhD, CPT, a journalist, social epidemiologist, and cultural critic, holds the Daniel Renberg chair at the Medill School of Journalism, and is on the faculty of Northwestern University’s Institute of Sexual and Gender Minority Health and Wellbeing. A former writer for the Village Voice, Scientific American and the Guardian, Thrasher is the author of the critically acclaimed book The Viral Underclass: The Human Toll When Inequality and Disease Collide. [Photo by C.S. Muncy]