Yiming Ma on the Future of Censorship

In Conversation with Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan on Fiction/Non/Fiction

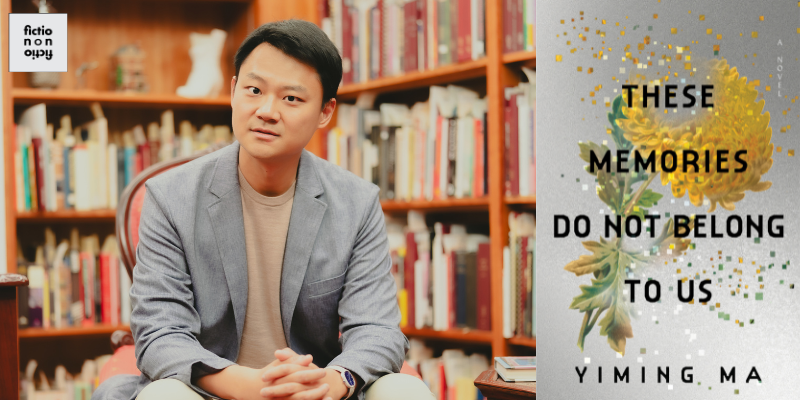

Fiction writer Yiming Ma joins co-hosts Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan to discuss his new novel These Memories Do Not Belong To Us. Ma, who was born in Shanghai and visited China frequently after immigrating to the U.S. and Canada, talks about how terrifyingly easy it can be to live in a society in which censorship is the default, and the dangers of self-censorship. Ma, who has an MBA, also reflects on the gap between how the tech and business worlds discuss artificial intelligence versus his peers in the arts. He explains how he developed the protagonist of his novel, a young man who struggles to decide what to do with an inheritance of forbidden memories; reflects on how his book’s structure, which moves between those memories, works as a “constellation novel,” in the tradition of Olga Tokarczuk; and considers how his characters demonstrate survival as a form of resistance. He reads from These Memories Do Not Belong To Us.

To hear the full episode, subscribe through iTunes, Google Play, Stitcher, Spotify, or your favorite podcast app (include the forward slashes when searching). You can also listen by streaming from the player below. Check out video versions of our interviews on the Fiction/Non/Fiction Instagram account, the Fiction/Non/Fiction YouTube Channel, and our show website: https://www.fnfpodcast.net/ This podcast is produced by V.V. Ganeshananthan, Whitney Terrell, and Moss Terrell.

These Memories Do Not Belong to Us • “When fear silences the writer” – The Globe and Mail

Others:

Robot: Mere Machine to Transcendent Mind by Hans Moravec • Flights by Olga Tokarczuk • “The Purloined Letter” by Edgar Allan Poe • “Mirrors, Memories, Rebellions: An Interview with Yiming Ma” Chicago Review of Books • Fiction/Non/Fiction Season 8, Episode 51: Omar El Akkad on Gaza and Western Empire

EXCERPT FROM A CONVERSATION WITH YIMING MA

V.V. Ganeshananthan: Your book, creepily, terrifyingly, explores a world where government control comes to an extreme and people comply in advance, sometimes censoring themselves. We want to start off by asking you about the current state of censorship, a phrase I never wanted to use. Jimmy Kimmel’s late night show on ABC has just been reinstated after its suspension, and ABC took the show off the air as a result of pressure from Brendan Carr, Trump’s FCC chair, who was unhappy about comments Kimmel made about Charlie Kirk’s murder. Those were not illegal comments in any way. Lots of people thought that was censorship. I happen to agree. We’re also seeing the restriction of free speech, especially pro-Palestinian speech, on college campuses and elsewhere, and enforced through things like the control of curricula, denial of visas for international students, and a host of other things. What about the present environment of censorship worries you the most?

Yiming Ma: A lot of it frightens me. Just to give some context, part of the reason is that I was born in China and actually spent a lot of my life going back and forth. I immigrated when I was fairly young to New York and then Toronto, but went back to China, and spent a lot of summers there and interned there. I think one of the things that frightens me most about the idea of censorship is how easy it was to live in such a society when that was the default. As long as economic progress was happening and people were able to get on with their lives, it was in the background, and we were able to live without thinking about it for the most part. One of the reasons why it is so important right now in the media and in U.S. society is that it is a change. It is something that’s so different than what the American Dream promised my parents when we moved over. I’ve seen how it is possible to accept a world of censorship as a default.

Within my book, one of the things that frightens me most is the fact that with censorship, there’s often not a clear red line, right? You can’t talk about Charlie Kirk or talk about Charlie Kirk in a certain way and because the line is often blurry, the people who have the most to lose, or people who are afraid at all, will want to steer clear of that line. Censorship is not merely staying away from that line, it’s about making distance and being as far away as possible, often for the people whose voices are already being silenced in some way. This is something where, in my book, it’s not always clear. For instance, we talked about memories. It’s not always clear what memories are banned or illegal, why they’re banned, but I think the blurriness of that is often what creates more fear and generates more self censorship. And I think as long as it remains not crystal clear, that self censorship will be one of the most powerful ways for an authoritarian regime to maintain their power.

Whitney Terrell: One of the things that goes hand in hand with censorship, in my view, is misinformation. One of the reasons authoritarian governments need to censor what their citizens say is so that they don’t contradict lies that they’re telling to the people. Yiming, you have an MBA, as we noted in the introduction. America’s financial system has relied on, in ways that are not true in other countries, accurate to the best of our ability reporting of things like labor statistics, inflation. What we’ve noticed is that the Trump administration has started to try to create a system that is much more similar to China where the government can report whatever—at least as far as I understand it—whatever statistics they want and doesn’t necessarily have to reflect the actual reality of the economy. Is that fair to say?

YM: I think it’s hard to say that. When I wrote this novel, I’ve been really explicit during my interviews, I did not intend it to be any sort of an anti-China book or anything like that. I think the themes were always meant to be universal, which is why we’re discussing it relative to America today. But I do think that point about misinformation is really valid. As I was writing the book, that Orwell quote about whoever controls the past controlling the future, and whoever controls the present controlling the past, was going through my head. I think the idea of stats is really relevant. There have even been recent examples in China where, when youth unemployment stats were not going in a good direction, they actually took a pause in reporting them and went to revise how the stats were being calculated. I think going forward, the idea of controlling that narrative, controlling the collective memory, is something that we’ve seen throughout history for different regimes and empires to maintain their power.

WT: Yeah, not to pick on China. You could have said that Soviet Russia does that, or does it now under Putin. I haven’t really studied exactly how economic statistics are reported there. But there’s not the same sort of checks and balances, at least in a place like Russia, as there have been in America. It seems to me that the Trump administration is trying to demolish that system of independent checks and balances. Your book imagines a world where people can pay for access to each other’s memories, kind of like novel writing, or memoir writing, in a way, it’s a weird part of what we do. I also thought about AI, which is stealing content and repurposing it for dark entertainment, identity theft, misinformation, and other kinds of grift. Of course, AI can scour a massive amount of information very quickly and makes it possible to surveil people better and faster than we ever have. Can you talk about this relationship between technology and censorship?

YM: Throughout this tour, I’ve done so many events but this is the one where I talked about what I’m afraid of from the very beginning of the conversation, more than any other. It is scary to me. But what you just said, what’s scariest is the fact that, when you talk about AI being able to scour a vast amount of data very quickly, making it possible for the state to do more surveillance and so on, that’s something that when I talk to people in tech, because I did my MBA in the Bay Area, and still have friends who work in AI and work in tech, that’s something that doesn’t scare them quite as much. Not that they would support surveillance, but it’s more of the idea that, “Oh, AI is supposed to be this productivity tool, right? It’s supposed to be making more possible.” I’ve described it sometimes in conversation with others, or I’ve heard it described as almost like electricity, something that improves everything, if it’s being done for the right purposes.

In my book, the world is also reimagined as one in which the Chin Empire, or former China, has taken over. China, ever since 2016 during the Trump Administration, has been depicted as this villain in conversation and in rhetoric, and that rhetoric has become even more divisive throughout Covid and so on. One of the things that I’ve seen in the Bay Area is, one reason to allow fewer regulations on AI and these technologies we don’t quite understand as much is by painting China as this villain. The fact that if we don’t improve technologically and be on the forefront, China is going to get there, and then that will be a worse world for it. And so that’s frightening to me.

WT: I want to just stop for a minute. All the way back when I was in college, a computer scientist named Hans Moravec, who was at Carnegie Mellon, wrote a book that basically had this argument, which I found to be totally insane. He’s like, “Robots will replace us.” He didn’t have the language for AI but he was like, “Robots will replace us so we don’t want it to be Chinese robots or like Russian robots. We gotta have American robots kill all the people so that at least they can preserve American values.” And I’m like “You are a maniac! This is an insane argument!” Anyway, it’s been around.

YM: I’ve literally watched interviews with Jeff Bezos and Mark Zuckerberg and all the major people talking about how they want American values to drive this innovation and to drive who decides how AI is used, because they see it as a tool, and they want Americans to be in charge of it. Now, we can go back and forth about whether that’s necessarily the best thing or the best country to be in charge of such a technology. But on a micro level, when I spoke to a lot of my classmates working in it, one frightening thing is they’re not really thinking about the ethics and morality of some of this, but they’re actually in a state of survival. A lot of these companies are really fearful that they’re not adopting AI fast enough, and that, if they don’t adopt it properly, if their people are not using it properly, their companies will fail, and they won’t be part of the conversation at all. It’s so different from the conversation that I’ve had with literary colleagues, with the fact that AI is trained on a fundamental sin, and all the issues of humanity that it’s coming up against. These are just different conversations. I’m afraid sometimes that as writers, we’re having a very different conversation than people who are actually driving the change and driving the progress in that technology. I wonder whether there’s a way for us to also be more part of that conversation and have our voices.

VVG: I worry a lot about this on my own campus where, for example, I see little to nothing reflecting the environmental cost. I have filled out every AI survey that I received from my institution saying we shouldn’t use AI. It is built off of my stolen work. There are active lawsuits about this. No one gives a shit what I say, as far as I can tell. My attempt to bridge this gap at all is—I’m sort of viewed like a maniac because of how much I’m afraid of it. So, when I got to the part in your book where there’s the young writer who’s like, “Will anyone read my work? I’m going to finish my novel. But, you know, will people even read novels anymore?” I felt such intense sympathy for this. I don’t know how we cross that divide if universities are not going to engage with this. I’ve never seen clear evidence that we’ve been corporatized.

I do want to pivot to talk more about your book, because one of the things that These Memories Do Not Belong To Us does is that it takes the form of a fictional and somewhat reluctant, wobbly response to the censorship of the distant future that you were describing. It’s from the point of view, broadly, of a son who has inherited what he realizes is a collection of forbidden memories gathered by his mother, and he has a clock ticking before the State shows up, as the State inevitably does, to collect estate tax and other things. But in his future, to say “You shouldn’t have these,” what are you going to do with these? The rest of the book takes the shape of the forbidden memories, and they range across time. They’re put into three timelines, before a war, during a war, and after a war. If you can just talk a little bit about this character’s predicament and the book’s form, which you refer to as a constellation novel, a phrase that I’ve seen in reference to Olga Tokarczuk’s work. Here, there is this interesting invitation at the beginning of the book that you could read the book in order. You also don’t have to, but also maybe, let’s see if you follow the order. I was like, “Oh, do I follow the order? I did. And then I was like, “Oh, my God, I’m such a square.”

YM: I have so many thoughts on that. I’ll start by talking a bit about the structure of the book. You’re exactly right. I think Olga Tokarczuk’s novel Flights was the first time that I heard of the term constellation novel, and I thought of that in two different ways. One, Olga’s book is such an inspiration. It’s made up of 116 different narratives written in different styles and lengths revolving around the themes of travel. I felt like with memories, I had a certain permission to do the same thing, because I knew how differently people perceive their memories. I can go into that more, but my wife’s actually a memory researcher as well, and I felt like the idea that memories might not be safe, especially during the beginning of Covid when that was originally a comforting thought for me, that we at least all had our memories, no matter where we were isolating, no matter if the world was being shut down. And then to imagine that wasn’t the case. That created a container that became the shape of this.

But more literally, I like the idea of the constellation novel, because I wanted these eleven forbidden memories each written in different styles. I wanted them to each have the ability to shine on their own, and to be able to be different and distinct and and and have their own voice, but at the same time come together via the themes and via the narratives and some literal connections as well between the stories to form that constellation, that greater narrative. So the compilation is how I created that structure. And I wanted readers. I wanted to offer readers that opportunity to read it out of order, because in some ways I feel as writers, especially anything resolving revolving around a story collection or novel stories, the reader does have that authority to read it out of order. In some ways, giving that permission allowed me to reclaim authority.

VVG: I sometimes have gotten grief from friends and others because I actually read out of order. When it’s not this kind of structure, I’ll skip around however I want. And then it was like, I felt like I was failing some sort of profiling. You had been like “It’s okay.” And I was like, “No, I have been told that I seek out spoilers in the wrong way.” All of a sudden, I was like, “Why am I approaching this in such a square fashion?” So it was this interesting and interesting indictment of my own reading style, when I was being given this permission.

YM: The funny thing is, when I was testing it, even before I decided to go out to agents or sell the novel—because this is my debut—I realized that almost everyone reads it in order. That gave me the confidence to say, “I will give you that permission. I will give that power to you and see whether you actually take it.” And on the issue of power, to answer that first question, I think that arc of the reluctant protagonist who receives that collection of memories, in some ways, mirrors my own journey. As a first generation immigrant, when I moved over here, my parents told me that I just had to accept the rules of the land. Capitalism was the dominant economic system, and that’s ultimately why I studied business and went to get my MBA. When I wanted to do good in the world, I left a corporate job and worked in impact investing, setting up affordable schools in different parts of Africa and Southeast Asia.

But that was still within the context of capitalism. I couldn’t imagine a world outside of it, and it was really only after writing that I started to question that, and tried to question the system. But the protagonist who receives that collection of memories, and ultimately, at the end, decides to release them, that’s almost the arc of my journey as a human, as a writer, as a citizen, but I’m not sure I almost reached that level of courage. I think I’m still working through it, and it was through the course of writing this book and creating these stories that deal with these themes of resistance and survival, that I realized I couldn’t shy away from it anymore. I have to own these stories and own the message behind them, but I’m still on my own journey, and still struggle with self censorship every day.

Transcribed by Otter.ai. Condensed and edited by Rebecca Kilroy.

Fiction Non Fiction

Hosted by Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan, Fiction/Non/Fiction interprets current events through the lens of literature, and features conversations with writers of all stripes, from novelists and poets to journalists and essayists.