This first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

My eyes have always been a problem. Without my glasses, I’d have been deemed legally blind before I turned ten; there is also a history of glaucoma and cataracts in my family. Still, it wasn’t until I began writing fiction that I realized that I suffered from another kind of blindness—one in my memories.

Show, don’t tell.

For years, I struggled with this mantra. At readings, I often got lost, struggling to imagine and hold onto scenes in my mind. Only when my longtime girlfriend began researching a rare condition known as aphantasia did we realize my connection to it: her lab’s questionnaire revealed that I was a mere three points from qualifying as someone who completely lacks imagery in their mind’s eye.

Suddenly, I had an answer for why my memories appeared mostly as language and intense emotions—in shades of black and grey. Why I could always remember what happened, but rarely how it looked. Later, when I interviewed other writers and creatives, I learned that many could even revisit their memories like a video game; by contrast, I counted myself lucky if I could recall a colored snapshot of my past for even a second.

Write scenes. Summaries are the devil.

It’s easy to dwell on the deficits of my near-aphantasia. But over time, I’ve also come to appreciate the sneaky superpowers it gave me. Before writing, I worked briefly on Wall Street in part because of my ability to juggle vast amounts of data in my head; after all, you didn’t need visuals to process numbers. But on the page, I’ve realized that my cognitive differences could occasionally prove to be assets too.

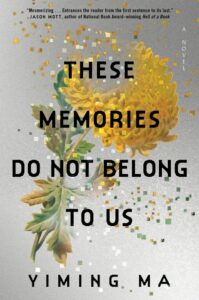

When I began sharing my debut novel These Memories Do Not Belong to Us—set in a future in which China has taken over the world and memories are bought and sold—I was surprised to find readers sometimes commenting positively on the imagery. Not the quantity, but rather the vividness of the brushstrokes I did use. Often, readers noted how the novel leaned into the interiority of my characters via other senses—for instance, the shame and fear manifested in their bodies, the details they ignored sometimes being more important than what they noticed. When visuals did appear, they were able to land with greater weight.

I believe that my near-aphantasia helps my prose stay taut, for the stories to maintain tremendous pace for a literary novel, especially one with worldbuilding. For instance, no matter how beautiful a lamp might appear in a scene, I will tend to focus on its effect on the characters—for instance, how the light might soften a face—rather than describing any objects that would already be familiar to those in the room.

Paint the picture for us.

Of course, there is risk in writing this way, especially for a more visual audience. But given the incessant emphasis on imagery in literature, I often find it impossible to truly forget about the cinematic aspects of any story.

When friends ask me how I write fiction with my near-aphantasia, I sometimes respond that I compensate with my other senses, similar to how the blind superhero Daredevil fights. Of course, this is a joke, but it is true that when I close my eyes, I am remarkably able to hear the emotional reverberations in a scene, to carefully listen and capture the different ways in which power ebbs and flows in a given space.

Every time someone says they can “see” my writing, I’m quietly astonished since I built the world nearly blind. Deep down, I also feel relieved because since the discovery of my cognitive difference, I sometimes also worry that it might disadvantage me on the page. By revealing my near-aphantasia, I hope that this may also inspire other writers who share my condition. Yet, to recall one final mantra, isn’t the real work of fiction to make the invisible visible anyway?

________________________________________

These Memories Do Not Belong to Us by Yiming Ma is available via Mariner Press.

Yiming Ma

Born in Shanghai, Yiming Ma spent a decade in the tech and finance world before writing the dystopian novel These Memories Do Not Belong to Us, set in a world where memories are bought and sold. He attended Stanford for his MBA and also holds an MFA from Warren Wilson College, where he was named the Carol Houck Smith Scholar. His stories and essays appear in the New York Times, The Guardian, The Florida Review, and elsewhere. His story “Swimmer of Yangtze” won the 2018 Guardian 4th Estate Story Prize. He’s a first generation immigrant and despite his travels, he’s still figuring out where home is.