Yang-Sze Choo on the Confucian Virtues and Man’s Transformation Into Beast

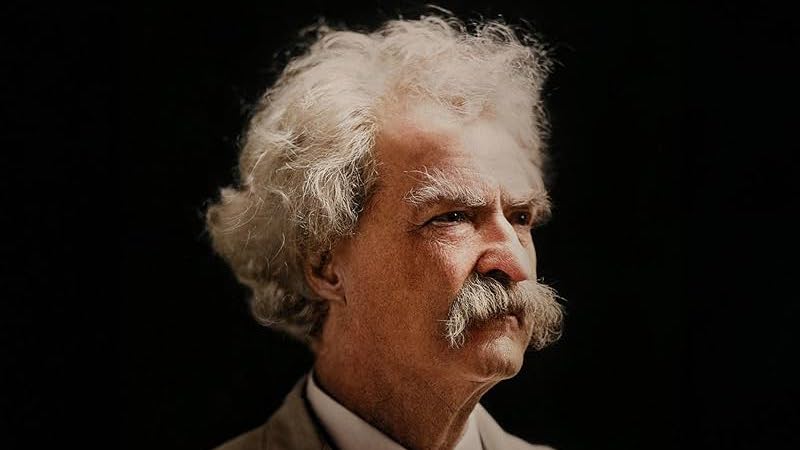

The Author of The Night Tiger Speaks to Gabrielle Mathieu on

the New Books Network

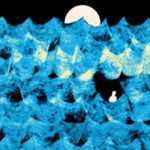

The Night Tiger is much more than just a fantasy novel—it’s also a mystery, a historical novel, and a love story. Yang-Sze Choo accomplishes all this in one deft package. Set in Malaysia in the 1930s, in the state of Perak, The Night Tiger closely follows three narrators, mysteriously interlinked by their names. There is a clever orphan named Ren who works as a houseboy, a spunky and funny young beauty, Ji Lin, and a British surgeon, William Acton.

Yang-Sze’s characters are engrossing, beckoning you into look deep into their psyches, and the setting of colonial Malaysia is a refreshing change to Eurocentric fantasy literature. A shimmer of the supernatural imbues the narrative, and a sense of transcendent beauty weaves its way through the chapters.

From the episode:

Gabrielle Mathieu: Most of the Chinese virtues like wisdom and faithfulness are apparent, but Li represents somewhat of a challenge: What does it mean to do things in the proper order? Could you give some examples to help your Western readers understand?

Yang-Sze Choo: Yes. I’ll try my best. So all the virtues, the Confucian virtues, are really actually—the five virtues are supposed to make up a whole human and these are all things that Confucius thought were very helpful. And, you know, I think as I mentioned all the virtues have deeper and broader meanings, right? Li, in this case, is something that a lot of people find different. Li, by Confucian terms . . . there is a ritual, there is a time and place to do everything.

So, for example, in those times filial piety was extremely important; if your parent died, there were a number of days mourning, depending on how close someone was to you, so I can’t quite remember all the times but if it was someone like a parent, you would be in mourning for something like three years. So if you’re actually following Li properly, then you would do the correct sequence of things, you would do everything in the right order, and there’s the intonation of keeping some sort of harmony and balance by doing that.

*

GM: So, your five characters are named after virtues. There’s a comment in your book, “A man who abandoned his virtue lost his humanity and became no better than a beast.” That brings us to the discussion of the were-tiger, and there’s one prowling around and it’s scary in various chapters. We believe that to be a man who has literally become a beast; he has a preference for long-haired women whom he dispatches. Does a man literally have to become a beast to lose his virtue? Are there metaphorical beasts in your novel?

YSC: Yes. I think you’re bringing up a great point, and once which I thought about when I was writing. You know, when we’re talking about dualities and mirror-worlds, it does makes us think of the whole Jekyll-and-Hyde thing, like, who are you when you look in the mirror? Who looks back at you, right? And the metaphor of the beast, the rear-creature, the shape-shifter, you will find that in many, many different cultures and I do believe that it is also that question, that curiosity we have of who is this person? Can I trust them? Where did they come from? What are they doing? And a beast in some ways transcends social mores; a werewolf will kill and eat, which we’re not supposed to do. So there is some sort of frisson—what does that actually mean?

And I thought, that was an idea that came up a lot when I was writing. The characters in the novel all have to make decisions. Some of them more moral than others, but that’s always the question—and it’s also I think part of walking the Confucian path. Are you walking those decisions? Why are you making decisions? And if you lose all your social mores, what does that make you? What is the essence of civilization? Isn’t it an artificial construct? So yeah, that is what I was thinking. And you are right, the shadow of the beast within us I think lurks throughout the book.