Yan Lianke on Intoxicated Revolutionaries and the Importance of

“Literary Distance”

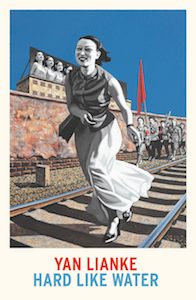

The Hard Like Water Author Discusses His Newly Translated Novel

and the Art of Storytelling

I spoke with Yan Lianke over WeChat in early June. His profile picture is a golden sculpture of a man with sunken eyes, contracted brows, and a soft frown hanging slightly towards one side of his face, as though troubled by something. This image hovered next to Yan’s name as he carefully and thoughtfully answered my questions. We discussed his newly translated novel Hard Like Water, the challenge and necessity of finding the right language for every story, and our connections to the places we left long ago.

*

An Yu: Where did the inspiration for Hard Like Water come from?

Yan Lianke: The story came to me by pure chance. Around 1999, following the publication of The Passage of Time, my health had been improving after ten years of illness. I felt revitalized, like the rays of life had once again blessed me with their warmth. Around the same time, I returned to my hometown and visited an old friend from the military. While I was there, he showed me some rare records from the public security department that were dated during the Cultural Revolution. I found them interesting, so I went through and read them all. One of the cases, which went on to become the inspiration for Hard Like Water, was the confession of an activist who traveled to Beijing to attend a conference on the Selected Works of Mao.

After the conference ended, he shared a train back to Henan with a woman who had also attended the conference. They didn’t speak a single word to each other, yet, as though it was the most natural thing to do when they disembarked the train in Zhengzhou, they walked along the tracks towards the cornfields, made love, and went their separate ways. Sometime later, this man became promoted and was put in charge of the army’s canteen. He was taken in for interrogation over an incident regarding missing food stamps. The man didn’t offer anything information regarding the food stamps. Instead, he confessed about the day in the cornfields.

The story of Hard Like Water became complete in my mind the moment I finished reading these records. I went back to Beijing, found a copy of People’s Daily newspaper from that period, and set it on my desk alongside a copy of Quotations from Chairman Mao. I sat down and the story poured out of me like a faucet that couldn’t be shut. Despite only being able to write for two hours a day due to poor health, I finished a draft in under half a year. I went through and lightly edited the manuscript once before sending it to the publisher. Even though Hard Like Water was almost censored upon publication, I still get a sense of comfort and nostalgia when I think back to those days and the jet stream style of writing that gave birth to this wild novel.

AY: I could really feel that “jet stream” pouring out on every line. For the most part, this is such an intense piece of writing, which is why the beginning seems exceptionally memorable to me. The first few lines of the book are rather composed and serene, and then a sudden change in tone launches the novel up to a level of intensity that sustains until the very end. Why did you choose to write the novel in flashback?

YL: Perhaps it’s because having someone who is narrating the story in such an unrelenting manner—despite being on death row—better reflects the essence of the “revolutionary youth” during that time. Today, it’s difficult for us to truly understand those seemingly intoxicated revolutionaries, with veins filled with boiling blood and an utter fearlessness in face of death. If we can somehow grasp this mentality, it wouldn’t be difficult to comprehend the characters in this novel.

AY: Let’s talk a little about language. The intensity I was talking about is, in my opinion, primarily achieved through language. Language varies greatly across your novels, and I imagine that for a novel like Hard Like Water, the distinct language in here is key to the telling of the story.

Every story should be told with its own unique language, but to find this language is an incredibly difficult task.

YL: Language is of utmost importance in this novel. Without the specific language here, the story of Hard Like Water wouldn’t exist. I must admit that the first thing that came to me was not the story, but the language. Ever since I began writing, I’ve been fiercely drawn to the language of the communist revolutionaries of that time. I grew up in that era, which is to say that I was nurtured by this kind of “revolutionary language”—it runs through the blood of our generation.

AY: What is your process of searching for and discovering the type of language that befits every story you tell?

YL: It is my hope that all my novels are vastly different in many ways, including the way of language. For a writer, the most challenging undertaking is to write in more than one kind of language. I believe that a few of my books, including The Years, Months, Days, Hard Like Water, and Lenin’s Kisses, have all achieved this. To find the type of language that is best suited to a particular story, there is no other way than to be attentive and observant in your life. Every story should be told with its own unique language, but to find this language is an incredibly difficult task. As I get older, I often experience creative stalls, and such moments are always when I fail to find the fitting language for a story, no matter how carefully I search for it in my reading and daily life. It makes me restless and anxious to know that the day my language source becomes depleted will be the end of my writing career.

AY: There are so many stories written about the Cultural Revolution, yet not many are told from the perspective of revolutionaries. I find that, despite being set in a unique period in history, this novel transcends its time and geographical constraints to establish itself as a study of the fundamental human condition that rings true even in today’s society. Human desires are strong in here; the loss of reason that comes from satisfying these desires is even more consuming.

Gao Aijun is a revolutionary, but he is also a victim and a subject. Not only him, but all the characters in the book seem to be controlled by an invisible hand, without any of them having much self-awareness. Gao Aijun is a relatively simple person. He is young, energetic, and zealous. He goes through life like an unrelenting flame seeking oxygen. Does writing this novel from the perspective of such a man better reflect human nature?

YL: Literature, after all, is an art that begins with people and ends with characters. One of the most important purposes of literature is to act as the link between people, characters, and language. Gao Aijun is a revolutionary but also an ordinary person. He is mad but his heart is pure. He retains everything humans are born with, yet his mind is overflowing with acquired romantic and utopian ideology. All of this is tightly interwoven with the uniqueness of such an era in human history. In fact, it wouldn’t be wrong to say that he is the personification of a piece of East Asian—specifically Chinese—history.

Today, decades later, I am still noticing reflections of Gao Aijun and Xia Hongmei among the youth in the country. My hope is for Hard Like Water to become irrelevant and obsolete in today’s reality. It’s saddening to be confronted with a truth that is quite the opposite.

AY: You’ve mentioned in previous interviews that you find it difficult to write stories that are set in the city because you have always felt like an outsider in the context of an urban environment. Even though you and I differ quite a bit in our experiences, I go through a similar struggle. I left Beijing when I was 18 years old and have lived abroad for over ten years, yet I feel that I can only write stories that are set in Beijing.

To be honest, when I was there, I was still a child and knew very little about the city, but I feel that I am more familiar with the city of Beijing than with any other place I’ve lived in ever since. I have this deep fear that my memory of Beijing will no longer be real over time. Memories are unreliable. I often wonder whether those familiar things in my mind are, in fact, inaccurate and untrue in the past or present reality. If I am drifting further away from Beijing, how can I have the confidence to continue writing about that piece of land? Perhaps that is what fiction is for?

YL: What you’re saying is correct. There should be a “literary distance” between a writer and a place. For writers, those places where they spend their years growing up always carry some of the most important materials for their work. These gardens of memories, after being washed over by time, will inevitably see many changes. Plants and flowers have grown and withered, but they encourage the writer to go on believing that they’ve remained the same as always. This very belief—this “literary distance”—is wherein lies the beauty of fiction.

The Beijing you write about will forever be your Beijing. It will not belong to anybody else. The further you are from that city—psychologically and not physically—the more the city will come alive. There is no need to be physically tied to that place of yours forever, so long as you are connected to it in your mind and your heart.

This very belief—this “literary distance”—is wherein lies the beauty of fiction.

AY: It is comforting to hear this because I rather enjoy writing about Beijing from afar. Distance sometimes offers me clarity, and, at other times, drapes a veil of mystery over the city. If I lived amongst it all, I’m not sure I would’ve been able to write what I’ve written.

YL: I strongly believe the distance between a writer and a piece of land must be delicately balanced. If this distance is too far, the spiritual connection will be lost. Too close, they will unwittingly lose themselves in the muddy waters of its routine. I hope to live in China’s reality; not the reality of the place I grew up. At the same time, China’s reality is closely related to that piece of land, which is then deeply tied to the world. Through literature, a village can become a country or an entire world, and in some cases, it can become something even bigger.

AY: How does living in Beijing affect your perception when writing about rural China?

YL: When I am watching that faraway village from here, I often feel like that village is the capital—the center—of China. Yet when I am in that village looking at Beijing, I feel that Beijing is the world, and the village under my feet is an observatory looking out at the vastness of the world.

AY: What have you been working on lately? Has the pandemic affected your writing routines?

YL: The most notable change is that I don’t go out much anymore and have been utilizing that time to focus on writing and reading. Since the beginning of the pandemic, I’ve written a novel that was recently published in the magazine Flower City. I’m currently working on finishing a draft of another novel.

__________________________________

Hard Like Water is available from Grove Press. Copyright © 2021 by Yan Lianke. Translated from Chinese by Carlos Rojas.

An Yu

An Yu was born and raised in Beijing, and left at the age of eighteen to study in New York at NYU. A graduate of the NYU MFA in Creative Writing, she writes her fiction in English. She is twenty-six years old and lives in Beijing. Braised Pork is her first novel.