Writing Yourself Into Existence: On Loving Worlds Where We Don’t Belong

Abdi Nazemian: "My empathy is big enough to let me love something (or someone) even if they have not pledged allegiance to me..."

“It comes as a great shock to discover that the flag to which you have pledged allegiance has not pledged allegiance to you. It comes as a great shock to see Gary Cooper killing off the Indians and, although you are rooting for Gary Cooper, that the Indians are you.”

–James Baldwin

*Article continues after advertisement

Before moving to the United States at ten, I grew up surrounded by other Iranians. Aunts, uncles, cousins, and family friends who spoke my language and understood the nuances of my life. Then, in the suburbs of America, I suddenly understood isolation and loneliness. I was the new, dark kid from the country who took Americans hostage, the kid whose name, tastes and mannerisms were easy to mock, who didn’t know the rules to American sports or culture. My refuge from alienation came through stories. I came home from school every day and buried myself in fiction because it felt like the real world had no space for me. But the irony is that the fictional worlds I was most obsessed with had no place for me either.

My twin obsessions were Old Hollywood and Archie Comics. Both ignited my fantasies of what America could be, though my own American life bore no resemblance to either. I dreamed of being as popular as Archie Andrews, fantasized about being transformed from a dull kid into a magnetic force like Rita Hayworth or Marilyn Monroe or any of the stars Madonna sang about in “Vogue” (except Joe DiMaggio, because that would’ve required playing sports). As a child, I didn’t understand that these worlds had no place for a queer Iranian like me. I hadn’t read Baldwin yet, didn’t even know that being queer was an identity and a community. I simply wanted to belong, and the easiest way was to imagine myself in a comic book malt shop or in a Technicolor musical.

I simply wanted to belong, and the easiest way was to imagine myself in a comic book malt shop or in a Technicolor musical.

Baldwin likened the consumption of white movies by a person who is othered by them as “a kind of psychological warfare in which you may perish.” Perhaps I made it through the warfare because I never fit in anywhere, a harsh reality that has helped me handle the dissonance of living in a divided world. I was forced from a young age to accept that no community or person could understand or fulfill me completely. I grew up too gay for the Iranian community and too Iranian for the western gay community of my era. My life was a divided one. Western queer people often tried to turn my family and the Iranian community into the antagonists of my story. They spoke the language of American self-empowerment, which tells us that if someone doesn’t immediately accept us as we are, we should bid them goodbye.

I spoke the language of immigrant families, which taught me that family loyalty comes before everything else. I often found myself defending my family and culture when in the company of queer Americans, then defending queer culture to the Iranian community. Never fitting in was hard, but it was also a gift. It allowed me to see the nuance in humans and to love them even if they couldn’t accept me fully yet. And most importantly, it forced me to create a world where I could be my whole self.

Stories are how I made sense of the world in my youth. They helped me transcend my pain and dream of a more vibrant, fully realized life. As an adult who wanted to understand myself and my history in a deeper way, I searched for stories about gay Iranians. There were none, a harsh reminder that I lived in a world that preferred me invisible at best and dehumanized at worst. I decided I had to write myself into existence by telling stories about queer Iranians.

Writing fiction terrified me and still does. I had to take the TOEFL (Test of English as a Foreign Language) to get into a good college because no matter how much I loved reading and writing, I could not master those sections of the SAT. I didn’t feel I had the linguistic skills needed to write prose. But I also knew that I had stories in me that demanded to be told, and that to tell them I would need to follow Baldwin’s advice for survival: “You have to really dig down into yourself and recreate yourself, really, according to no image which yet exists in America…You have to decide who you are, and force the world to deal with you, not with its idea of you.”

When my first novel The Walk-In Closet was published, no image of me existed in America. I’ve been told by academics that it’s the first novel ever to focus on a gay male Iranian lead character. It was published in 2014. Queer Iranians, and so many other marginalized people, are still doing the hard work of forcing the world to deal with us, one story at a time.

Never fitting in was hard, but it was also a gift. It allowed me to see the nuance in humans and to love them even if they couldn’t accept me fully yet.

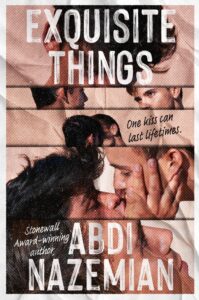

I’ve tried to tackle the nuances of loving artistic worlds that feel both liberating and isolating in my writing. In my novel Only This Beautiful Moment, an intergenerational story of three Iranian men in the same family, the eldest character comes of age in the Old Hollywood of the 1930s, the world I once dreamed of escaping into. His journey from young MGM actor to proud Iranian is the embodiment of Baldwin’s quote about Gary Cooper. And in my latest century-spanning novel, Exquisite Things, I explore multiple subcultures that give the novel’s characters new worlds of fantasy to escape into, from the queer underground of post-WWI Boston to the club scene of Thatcher-era London.

In writing this novel, I started to understand that perhaps my passion for art that excluded me was once about escape, but now it’s simply about love. I still love Archie Comics and Old Hollywood films despite their flaws, just as I love humans despite our flaws (or perhaps because of them, because what makes us more lovable than our imperfections?). In Exquisite Things, I write, “Love is the only thing worth living for. Not just romantic love. All of it. The love of family. Of community. The love we feel for a poem or a song or a moment in time.”

My purpose as a storyteller is first and foremost to give young people the chance to be seen and represented in the art that is available to them. As for me, I’m grateful to the art I was obsessed with in my youth, no matter how much it excluded me. I learned so much from Betty and Veronica and also from Bette and Joan. Perhaps this is the ultimate lesson I’ve learned from these art forms I was enamored with as a child: that my empathy is big enough to let me love something (or someone) even if they have not pledged allegiance to me…yet.

__________________________________

Exquisite Things by Abdi Nazemian is available from HarperCollins, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishing.

Abdi Nazemian

Abdi Nazemian is the author of Only This Beautiful Moment—winner of the 2024 Stonewall Award and 2024 Lambda Literary Award—and Like a Love Story, a Stonewall Honor Book and one of Time magazine’s 100 Best YA Books of All Time. He is also the author of the young adult novels Desert Echoes, The Chandler Legacies, and The Authentics. His novel The Walk-In Closet won the Lambda Literary Award for LGBT Debut Fiction. His screenwriting credits include the films The Artist’s Wife, The Quiet, and Menendez: Blood Brothers and the television series Ordinary Joe and The Village. He has been an executive producer and associate producer on numerous films, including Call Me by Your Name, Little Woods, and The House of Tomorrow. He lives in Los Angeles with his husband, their two children, and their dog, Disco. Find him online at abdinazemian.com.