Writing Toward a Definition of Indigenous Futurism

Chelsea Vowel: “Stories, like all language, have power.”

Stories are an inherently collaborative experience, and all stories have a purpose. Among Métis and nêhiyawak, as with other Indigenous peoples, there are âcimowina (everyday stories), kwayask-âcimowina (non-fiction), kîyâskiwâcimowina (false or fictional stories), âtayôhkêwina (sacred stories), mamâhtâwâcimowina (miraculous stories), pawâmêwâcimowina (spiritual dreaming stories), kiskinwahamâcimowina (teaching stories), kakêskihkêmowina (counselling stories), wawiyatâcimowina (funny stories), stories that map out terrain and resources, kayâs-âcimowina (stories that pass on history), miyo-âcimowina (good stories), and mac-âcimowina (evil or malicious stories).

These genres within Métis/nêhiyaw (Cree) literary tradition have their own forms and literary conventions, some of which I use in my stories. I blend these with whitestream genre writing without necessarily making the Métis/nêhiyaw allusions and conventions legible to non- Métis/nêhiyawak, such as in “Dirty Wings,” where I use seasonal rounds, allude to specific âtayôhkêwina (sacred stories), and reference Elders’ counselling discourse patterns, which “work rhetorically to effect learning in the reader.” [1] In this way I am making space to respond to mainstream speculative fiction either by Métis-fying it (adding Métis literary conventions and allusions/history/cultural aspects) or subverting it by switching observer-subject roles.

It is important to understand that within otipêyimisow-itâpisiniwina, stories, like all language, have power. Language is not merely a tool of communication, but also a place where reality can be shaped. Language is transformational; “our breath has the power to kwêskîmot, change the form of the future for the next generation.” [2] My writing seeks to engage in that transformation, making space for Métis to exist across time, refusing our annihilation as envisioned by the process of ongoing colonialism, and questioning the ways we are thought to have existed in the past.

Through stories like these, I wish to extend Métis existence beyond official narratives, beyond current constraints, and imagine what living in a “Métis way” could look like in spaces and times we haven’t (yet) been. This challenges the divide between fact and fiction, as Métis people assert a reality that is perceived as impossible in mainstream thinking. If Métis people say a thing is possible, who gets to determine that that thing is fictional?

Grace Dillon first coined the term “Indigenous futurisms” in 2003, seeking to describe a movement of art, literature, games, and other forms of media which express Indigenous perspectives on the future, present, and past. More specifically, she argues that all forms of Indigenous futurisms “involve discovering how personally one is affected by colonization, discarding the emotional and psychological baggage carried from its impact, and recovering ancestral traditions in order to adapt in our post–Native Apocalypse world” (2012, Walking the Clouds: An Anthology of Indigenous Science Fiction).

Uncovering Black/Indigenous presence in the past, then asserting our existence in the present and into the future can be a way of seeing into, or even making, better futures.

Indigenous futurisms are not merely synonymous with science fiction and fantasy, despite how they may be viewed as such within the mainstream. Indigenous futurists express their ontologies in various forms, and as Grace Dillon puts it, “our ideas of body, mind, and spirit are true stories, not forms of fantasy.”

For example, Tsilhqot’in filmmaker Helen Haig-Brown’s short film The Cave is listed on IMDB as being science fiction, but it depicts atraditional Tsilhqot’in story told to her by her great-uncle, Henry Solomon. Indigenous futurisms offer an alternative genre to Indigenous creators that allow us to foreground our worldviews and realities.

Although Indigenous futurism has only in the past decade taken root as a named and self-reflective movement, it does so with inspiration from—and is indeed indebted to—the path-breaking work of Afro futurists such as Sun Ra, Octavia Butler, Janelle Monáe, Samuel R. Delany, Nalo Hopkinson, and so many others.

Afrofuturisms—so named in 1994 by Mark Dery, but referring to works beginning in the late 1950s and arguably much earlier—explore the intersection between the African diaspora and technology. Afrofuturism centres Afrodiasporic experiences and cosmologies across a vast range of themes, offering alternatives to Western views of Africa and of the African.

Dillon points out that science fiction as a genre “emerged in the mid-nineteenth-century context of evolutionary theory and anthropology profoundly intertwined with colonial ideology.” These themes are exhaustively explored in whitestream science fiction, exposing particular settler colonial anxieties and aspirations that tend to erase or completely ignore the experiences and perspectives of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC).

In (re)imagining history, whitestream speculative fiction is particularly adept at repressing the violent histories of colonialism from the public imaginary. [3] This does not mean that the topic of colonization is absent from science fiction—far from it. We find constant dichotomous reframing of settler colonials as agents of space-faring Manifest Destiny or the inevitable subjects of colonization at the hands (tentacles, squishy pseudopods, or furry appendages) of aliens. [4] Whitestream science fiction insists that colonialism is inevitable. It’s “us or them,” and it had better be “us.”

Increasingly, BIPOC are becoming content creators, operating from within worldviews that exist beyond the whitestream. Much of this work involves switching observer-subject roles, so that instead of BIPOC being under the external gaze of the white anthropologist colonizer (the subject), we are viewing the outsider through our own cultural lenses (the observer). This is not merely a pushback against the colonizing narrative of whitestream speculative fiction; it can also be a form of social justice organizing.

As Walidah Imarisha puts it, “whenever we try to envision a world without war, without violence, without prisons, without capitalism, we are engaging in speculative fiction. All organizing is science fiction.” [5] Dillon takes the transformative potential of the work even further, stating that “this process is often called ‘decolonization’ and as Linda Tuhiwai Smith (Maori) explains, it requires changing rather than imitating Eurowestern concepts.”

Before I get into explaining what I mean by “Métis futurisms,” I want to acknowledge what Lou Cornum rightfully points out in their MA thesis, “The Outer Space of Blackness and Indigeneity in Midnight Robber and The Moons of Palmares”: that the term “Indigenous” is often used in a way that implicitly excludes Black people from its definition, either denying the Indigeneity of Black people or avoiding the question altogether.

Speaking of the “space Indian” as a diasporic figure, Cornum suggests that Indigenous futurists can “participate in complicating our notions of home, Indigenous identity, and shifting relationships to land and belonging” in ways that “evoke similarities with other diasporic figures… specifically… the Black diasporic figure.”

I refuse to exclude the potential and real Indigeneity of Black people, either implicitly or through omission. I take seriously the assertion that “the coupled structure of settler colonialism and slavery calls for new understandings of Indigeneity that can account for diaspora of Indigenous peoples and alternative forms of belonging not dependent on sovereignty over an ancestral territory.” While the stories contained in my book do not all directly address Blackness and Indigeneity, these complexities are part of the theoretical framework I am working from; they are foundational aspects of the world building that I do here and will continue to do.

The futures I envision include expansive notions of Indigeneity, according to the principles of wâhkôhtowin (expanded kinship, including with nonhuman kin), miyo-wicêhtowin (the principle of getting along with others), miyo-pimâtisiswin (the good life), and wîtaskiwin (living together on the land). When I speak of Indigenous peoples, I am not limiting myself to First Nations, Métis, and Inuit of North America, but rather to Indigenous peoples globally, recognizing that these definitions are fraught, contested, and, like all definitions of what it means to be human, often rooted in anti Blackness (The Problem of the Human: Black Ontologies and ‘the Coloniality of Our Being’).

Octavia Butler’s work expanded my understanding of what is possible in terms of speaking back to mainstream (and mostly white) visions of the past and future. Butler’s work never elides or pretends to solve racism, misogyny and misogynoir, ableism, homophobia, classism, or any other system of oppression, neither do these structures forbid Black possibility; they exist as they do now, as constraints that must be contended with and resisted.

This approach differs from that of popular mainstream science fiction, in particular, Star Trek the Original Series and Star Trek: The Next Generation, in which it is imagined that in the twenty-third and twenty-fourth centuries, humans have somehow solved all of these structural oppressions.

Star Trek “is so invested in its liberal humanist multicultural utopian vision, that it can’t reckon with the ways in which it replicates fundamentally oppressive and hierarchical power imbalances, especially through its promotion of Starfleet as a militaristic, interventionist (in spite of the Prime Directive) organization” (Molly Swain). Unsurprisingly, this vision of the future mirrors contemporary refusals to acknowledge structural oppression or to understand the intergenerational impacts of settler colonialism and the transatlantic slave trade.

This kind of future imagining requires a form of forgetting that Black scholars like Christina Sharpe), Robyn Maynard, Sarah-Jane Mathieu, and Rinaldo Walcott all work to resist. Uncovering Black/Indigenous presence in the past, then asserting our existence in the present and into the future can be a way of seeing into, or even making, better futures. To me this is a major component of Indigenous futurisms.

*

[1] MacKay, Gail. 2014. “‘Learning to Listen to a Quiet Way of Telling’: A Study of Cree Counselling Discourse Patterns in Maria Campbell’s Halfbreed.” In Indigenous Poetics in Canada, ed. Neil McLeod, 351–369. Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

[2] Beeds, Tasha. 2014. “Remembering the Poetics of Ancient Sound kistêsinaw/wîsahkêcâhk’s maskihkiy (Elder Brother’s Medicine).” In Indigenous Poetics in Canada, ed. Neal McLeod, 61–72. Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

[3] Gaertner, David. 2015. “‘What’s a Story Like You Doing in a Place Like This?’: Cyberspace and Indigenous Futurism.” Novel Alliances. March 23.

[4] Justice, Daniel Heath. 2018. Why Indigenous Literatures Matter. Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

[5] Imarisha, Walidah. 2015. “Introduction.” In Octavia’s Brood: Science Fiction Stories from Social Justice Movements, eds. adrienne maree brown and Walidah Imarisha, 3–6. Oakland: AK Press.

__________________________________

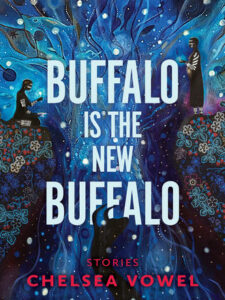

Excerpt from Buffalo Is the New Buffalo by Chelsea Vowel. Reprinted with permission from Arsenal Pulp Press. Copyright © 2022.

Chelsea Vowel

Chelsea Vowel is Metis from manitow-sakahikan (Lac Ste. Anne), Alberta, and currently residing in amiskwaciwaskihikan (Edmonton). Mother to six children, she is a writer and educator, co-host of Indigenous feminist sci-fi podcast Metis in Space, co-founder of the Metis in Space Land Trust, and author of Indigenous Writes: A Guide to First Nations, Metis & Inuit Issues in Canada.